Entertainment

Wrong court, real crisis

As of the end of last year, Pakistan’s courts were sitting on roughly 2.3 million unresolved cases. Nearly 83% were pending in the district judiciary; the remainder was spread across the high courts, the Federal Shariat Court and the Supreme Court.

The SC’s share hovered in the mid-50,000s, a few percentage points of national pendency at most.

Within the superior courts, constitutional work is concentrated rather than dominant: at the Lahore High Court, for example, writ and constitutional matters are about 84,000 out of roughly 179,000 pending cases, close to half of that court’s own docket, yet that entire stock is still a sliver next to the millions of cases stuck below.

Pakistan’s backlog remains, by any measure, overwhelmingly a trial-court problem.

Against that data, parliament has moved with unusual speed. In a short span, a constitutional amendment that creates a Federal Constitutional Court (FCC), shifts constitutional jurisdiction away from the existing Supreme Court and touches sensitive questions of state design has been pushed through, with little committee scrutiny or public engagement.

The government’s explanation is simple. The SC, we are told, is drowning in constitutional and ‘political’ litigation, which has crowded out ordinary appeals. The FCC is offered as the solution: it will take on the constitutional load; the Supreme Court will focus on its appellate role; and the pendency will fall.

The statement of objects and reasons to the Constitution (Twenty-seventh Amendment) Act, 2025 says as much, blaming an “increasing number of constitutional petitions” for delays in regular cases and promising that a specialised court will “significantly reduce pendency”.

That narrative has already been challenged from within the system. Former chief justice Jawwad S Khawaja has taken the amendment back to the court he once led, warning that it will weaken the state, unsettle the separation of powers and erode the consensus around the 1973 constitution.

Since then, the debate has moved from draft to fact. President Asif Ali Zardari has now signed the 27th Amendment into law, creating the new office of the chief of defence forces and establishing the FCC as an operative reality rather than a proposal.

In response, three senior judges, SC justices Syed Mansoor Ali Shah and Athar Minallah, and Lahore High Court Justice Shams Mehmood Mirza have resigned in protest, describing the amendment as an assault on the constitution and on judicial independence.

The question for this piece, however, is narrower: if the claim is that the FCC is about backlog relief for the ordinary litigant, do the numbers support that claim?

The SC’s pending caseload has risen from roughly the mid-20,000s in the mid-2010s to around 40,000 by 2018 and past 50,000 by 2021 into the mid-50,000s in 2024–25.

Set against the nationwide stock already noted above, this makes the apex court a small but visible pocket of congestion rather than the epicentre of delay.

Constitutional work, even where it clusters, is numerically marginal once you zoom out from the superior courts to the system as a whole. Even in high courts where writ and constitutional matters occupy a large share of the local docket, that entire layer sits on top of a system in which more than 2.3 million cases are pending, the vast majority in the trial courts.

On any realistic view, the SC’s constitutional workload therefore sits well below even one or two per cent of the national total; even if every case on its list were re-badged as ‘constitutional’, it would still barely dent the overall numbers.

The court itself has acknowledged that a large portion of its docket consists of review petitions rather than fresh constitutional challenges. And in its own case law on special courts, it has warned that creating new forums or simply adding judges does not cure delay; the real work lies in case and court management, especially in the lower tiers.

Taken together, the data and the doctrine point in the same direction: Pakistan’s backlog is overwhelmingly a trial-court phenomenon. The problem the FCC is meant to solve is numerically marginal.

Under the 27th Amendment, the FCC is designed to exercise original constitutional jurisdiction —including federal–provincial disputes and many fundamental-rights questions while hearing constitutional appeals from the high courts.

The existing SC is recast as largely an appellate tribunal for other work. Ironically, even if one assumes, very generously, that a full one-third of current Supreme Court pendency is “constitutional”, we are dealing with perhaps twenty thousand such cases in a system of more than 2.3 million. On that assumption, the FCC’s core field of operation covers well under one per cent of the pending caseload in Pakistan.

Nor will the FCC simply inherit existing matters and work through them quietly. New courts generate their own litigation – jurisdictional contests between the Supreme Court, FCC and high courts, challenges to composition and appointments, fresh layers of appeal and review. A body created and justified as a relief mechanism for the “ordinary litigant” is, by design, aimed at the smallest and most elite slice of the docket.

All this might still be defensible if the FCC were cheap. It is not. The SC’s budget for 2023–24 is in the region of Rs3.5 billion, largely consumed by salaries and allowances.

A parallel constitutional court, with its own judges, registries, security, infrastructure and staff, will, even if initially lean, operate in the same order of magnitude.

Those billions are being contemplated in the middle of an IMF programme demanding tight fiscal consolidation, cuts in non-priority spending and difficult adjustments in social and development sectors. Meanwhile, the district judiciary, which carries more than four-fifths of the backlog, struggles with basic infrastructure, staff shortages and overburdened judges.

The same capital injected in trial-level capacity in the form of more judges and clerks, reliable process-serving, functional courtrooms, ADR mechanisms, case-flow management and IT would strike at the heart of delay.

Justice Khawaja’s petition therefore, reads less like a personal lament and more like a diagnosis. The amendment, he argues, is “so patently unconstitutional on the face of it” that it ought to have been rejected by parliamentarians sworn to preserve and protect the constitution.

An amendment that strips the SC of its constitutional powers “effectively abolishes [it] as a constitutional court” and is “clearly incompatible with the constitution”.

If the legislature and executive may abolish the highest court and substitute it with another forum manned by their nominees, they are empowered to “change the rules of the game as and when they deem fit” — a result fundamentally at odds with separation of powers and judicial independence.

The federal government asks us to see the FCC as a kindness to the ordinary litigant. The numbers suggest something else: that the new court is aimed not at the backlog of cases that burden citizens, but at the backlog of constitutional questions that burden power.

If it is to be born in the ordinary litigant’s name, the least we owe that litigant is honesty about what problem it is really being built to solve.

Originally published in The News

Entertainment

Dor Brothers, Tom Cruise, Brad Pitt shake industry

Artificial intelligence has stormed into Hollywood with breathtaking speed and alarming consequences.

What began as experimental novelty has now escalated into a full-blown industry crisis, as viral AI-generated films and hyperrealistic clips of A-list actors force studios, unions, and lawmakers to confront the future of entertainment.

Earlier this week, the Dor Brothers, Berlin-based AI Video Production company, claimed they had produced a “$200,000,000 AI movie in just one day.”

The video, created entirely with generative tools, went viral on X (formerly Twitter), amassing millions of views and sparking debate over whether AI can truly replicate blockbuster filmmaking.

Supporters hailed it as proof of a new era, while skeptics dismissed it as hype.

Regardless, the post underscored how quickly AI is encroaching on traditional production models.

Deepfake Shock: Tom Cruise vs. Brad Pitt in AI combat

If the Dor Brothers’ film was a provocation, the viral AI fight sequence between Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt was a shockwave.

Created with Seedance 2.0, the 15-second clip depicted the two megastars trading blows on a rooftop with uncanny realism.

Variations of the video circulated online, complete with dialogue and camera angles, leaving audiences unsettled.

Screenwriter Rhett Reese (Deadpool & Wolverine) warned bluntly, “It’s likely over for us.”

The clip crystallized Hollywood’s worst fears that AI could convincingly mimic actors without their consent, eroding both creative integrity and livelihoods.

SAG-AFTRA draws line on AI exploitation

In response, SAG-AFTRA has taken a hard line.

The union condemned Seedance 2.0’s use of actors’ likenesses as “blatant infringement” and called for an outright ban on AI creations featuring real movie stars.

It is argued that unauthorized replication of voices and faces undermines performers’ ability to earn a living and strips them of control over their identities.

The guild has worked for several years on AI protections, with demands for strict consent requirements, compensation frameworks and federal safeguards.

Hollywood Divided: Threat or opportunity?

Hollywood is now split between alarm and opportunity.

Unions, screenwriters, and many actors see AI as an existential threat.

They warn of job losses, creative theft and a collapse of artistic value if studios embrace AI without regulation.

Some studios and technologists argue AI can be a powerful tool if used responsibly for previsualization, special effects, or enhancing workflows.

They stress that AI is not yet capable of producing true 4K theatrical-quality films, highlighting its current limitations.

The Road Ahead: 2026 as a defining year for cinema

2026 is shaping up as a pivotal year.

With studios investing billions in AI, unions mobilizing for protection, and viral clips eroding trust, Hollywood faces a defining choice: embrace AI intelligently or risk chaos.

Entertainment

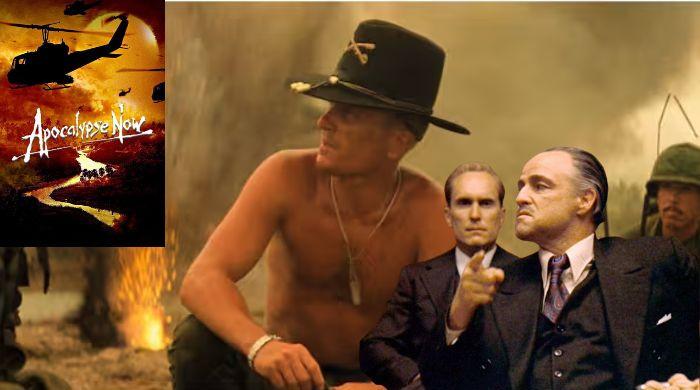

Why Robert Duvall’s ‘napalm’ line in ‘Apocalypse Now’ is so iconic

One of the most referenced and iconic dialogues in the history of cinema that truly enjoyed a life of its own is “I love the smell of napalm in the morning.”

These timeless lines were performed by Robert Duvall in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 Vietnam War classic Apocalypse Now.

The chilling monologue is what is making buzz on social media again after the demise of the Oscar winner for Tender Mercies, who passed away at his home in Middleburg, Virginia, on Sunday, February 15.

Let’s find out why, decades later, the monologue has become one of the most quoted lines in cinema history.

The line was said by Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore, a daring and eccentric cavalry officer, when he set a helicopter ambush on a Vietnamese village.

Colonel Kilgore calmly reflects on the ashes left after the napalm bombing, finally coming to terms with the fact that it smells like “victory.”

The line is, “Napalm, son. Nothing else in the world smells like that. I love the smell of napalm in the morning. You know, one time we had a hill bombed for twelve hours. When it was all over, I walked up. We didn’t find one of ‘em, not one stinking drink body.

“The smell, you know, the gasoline smell, the whole hill. Smelled like… victory.”

What follows is, “Some day this war’s gonna end.”

It was a quiet introspection of what war takes and steals from human lives.

Why does the line continue to resonate?

The dialogue has taken on a life beyond the film, becoming a symbol for glorifying chaos, dark irony, and battlefield arrogance.

Cultural critics have been referencing it across pop culture, memes, viral trends, and television shows, often using it with a taste of sarcasm to introspect obsession, destruction, or self-indulgence.

Above all, Robert Duvall’s iconic performance in the film, especially in the immortal sequence, has been etched into the memories of cinema lovers, as long as the shadows of war continue to loom over our planet.

Entertainment

Chinese ‘Year of Fire Horse’ to bring luck for Mamdani, challenges for Trump

China has welcomed its Lunar New Year with nationwide celebrations of fireworks, lanterns, and festivities.

2026 is the Year of the Fire Horse, which symbolises power and speed.

A feng shui expert Raymond Lo has made predictions on how the new year will be for prominent American personalities, including the United States (U.S.) President Donald Trump, New York Mayor Zohran Mamdani and Hollywood sensation Timothee Chalamet.

For context, a Feng Shui Master is a professional, often rooted in traditional Chinese metaphysics, who interprets and manipulates environmental energy (Qi) to enhance harmony, health, and prosperity in homes and businesses.

In an interview with CNN, Master Lo said, “The horse represents a powerful fire element. So it’s a pure fire year. Fire is very strong and very energetic.”

He added that it will bring protests and anti-government demonstrations in the U.S. that could not be so peaceful, adding, “Fire is not a favourable element for President Trump, so it will stimulate his enemies.”

Master Lo said Trump will likely face fierce opposition and significant obstacles in the year of the fire horse.

The year is predicted to be favourable for New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani, who was sworn-in last year after winning the election against political heavyweights.

Master Lo said, “Mamdani has a strong metal element in his chart, and fire is a power to metal people. He will gain power. It’s a very favourable year for him.”

The predictions don’t always come true as Master Lo’s prediction about then-President Biden having a good year in 2024 and Trump having a bad year did not come true, as Trump went on to win the 2024 presidential election despite Lo’s forecast.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoAye Finance IPO Day 2: GMP Remains Zero; Apply Or Not? Check Price, GMP, Financials, Recommendations

-

Fashion7 days ago

Fashion7 days agoComment: Tariffs, capacity and timing reshape sourcing decisions

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoRemoving barriers to tech careers

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week ago‘Harry Potter’ star David Thewlis doesn’t want you to ask him THIS question

-

Fashion7 days ago

Fashion7 days agoADB commits $30 mn to support MSMEs in Philippines

-

Fashion7 days ago

Fashion7 days agoSaint Laurent retains top spot as hottest brand in Q4 2025 Lyst Index

-

Fashion4 days ago

Fashion4 days ago$10→ $12.10 FOB: The real price of zero-duty apparel

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoWinter Olympics opening ceremony host sparks fury for misidentifying Mariah Carey, other blunders