Entertainment

A farce of a deal

With a mounting pile of scandals, each more gruesome than the other, it is awfully difficult to decide what to start with. From the purported plan to end the Gaza conflict to the Commonwealth Observer Group report, which has been made public after a criminal lapse of over 18 months, to the Shama Junejo episode, it appears that the unconstitutional and illegitimate government is finally unravelling.

The Trump plan for a settlement in Gaza is primarily an attempt to legitimise genocide. It has already taken over 65,000 lives, including children, those born and those still in their mothers’ wombs. The brutal and barbaric Israeli military assault, stretching to almost two years now, has reduced the entire strip into a sprawling rubble without any distinction made between work areas and residential quarters.

With no mention of the aggressor and whether it would be held to account for this unprecedented genocidal perpetration, no plan to set up a Palestinian state and no thought given to providing relief and reprieve to a starved and beleaguered people, the entire exercise comes across as a neo-colonial venture aimed at carving a lethal presence in the region to push it into permanent enslavement.

The capitulation of the entire Muslim leadership of the region is under acute public scrutiny and it appears no one will escape an indictment. How could one agree to a plan that does not ensure the rights of the Palestinian people to their own independent state, and how, even in their indescribable misery, could they be challenged to accept the draconian deal within a certain stipulated time frame or get ready for total annihilation? Is the world conscience dead? And what have the Muslim leaders sold their souls for?

Accepting the Trump Plan by the Pakistani government alongside heaping praise on its architect is spraying salt over the wounds of the Palestinian people and all those who have been fighting heroically for an independent state as a matter of their inalienable right. The world, including the US, through one accord or another, has been stamping its approval for a Palestinian state in the past, which it is now reneging on without a shred of compunction.

And imagine: one Tony Blair, someone who should be at The Hague facing charges for committing heinous crimes against humanity for his role in the war in Iraq at the behest of the US, has been proposed as the head of the Gaza International Transitional Authority. Obviously, never being the one with even a modicum of conscience for ensuring human rights, he comes across as an appropriate choice from among the lined-up criminals for continuing the genocidal spree against the Palestinian people. Commenting on the proposed appointment, somebody said in a recent television programme that this choice only reveals that Satan was not available for the job.

One understands that, due to the policies the state has pursued in recent years, it is vital for it to secure Western support, particularly that of the US. But, in doing so, it must also ponder that, by making strategic compromises of considerable proportions, its own sovereignty and independence will be tested gravely in times to come. This is what history teaches us, but it appears that we are reluctant to learn from it and are currently engaged in raising a castle on make-believe stories of being the favourite partners in this nefarious game plan.

The reason the state is behaving in an embarrassingly subservient manner can be traced to the contents of the Commonwealth Observer Group Report on Pakistan General Election of February 8, 2024. It has been released after a criminal lapse of over 18 months, and that, too, only when its contents were leaked by Drop Site. The Telegraph reported the news as “Commonwealth helped Pakistani election rigging”. The report only confirms one’s worst fears about how badly and blatantly the election was rigged to the advantage of certain parties, with an apparent intent to keep the most popular party and its leader out of power.

Besides making recommendations for conducting a comprehensive overhaul of the Election Commission of Pakistan and its functioning in various spheres, the report lists numerous critical steps taken to unfairly disadvantage one party. This encompasses issues about the entire election process during the run-up, election-day and post-election phases. It is a lethal indictment of the entire electoral process.

The group regards as fallacious the notion that security must come at the expense of democracy. It goes on to elaborate further that: there must be clearer demarcation between military and civilian authority in line with the country’s constitution and international law. That political parties and all organs of the state, including the military, must establish new rules of engagement that ensure the sanctity of democratic institutions and process, independent of the bounds of political manoeuvring. And that the judiciary should be able to act free from outside pressure.

The report has also listed scores of steps that interfered with the holding of free and transparent elections in the country. These related to restriction of fundamental political rights, limiting the ability of the PTI to contest the election fairly, pre-election steps impacting the concept of a level-playing field including non-allocation of the bat symbol to PTI candidates, limiting journalistic freedoms including in relation to speech and granting impunity to the perpetrators of a culture of violence against journalists, and the reported detention of PTI members with some undergoing unexplained periods of disappearance.

The shutdown of mobile phones on election night and the ruling party’s state control over media significantly reduced the fairness of the election process and impacted the efficiency of delivering results, which may have compromised the credibility, transparency and inclusiveness of the electoral process. A host of discrepancies between polling station results forms and tabulated results forms at the constituency level were noted, which may have resulted in some candidates being unlawfully returned.

This is as damming a report as any can be. After its release, the fraudulent February 8 elections are stripped of every shred of credibility and legitimacy. The state stands naked in the court of the people whose mandate it stole to hoist a bunch of favourites in the seats of power. Pakistan is poorer for this crass act of fraud, deceit and deception.

Manipulation within leads to weakness outside. This is a moment for serious introspection. In the absence of political and consequent economic and strategic stability, can Pakistan afford to continue sliding down the precipice? There is a need to think of a remedial strategy. One must face the reality that the existing fabricated system, sans even a modicum of legitimacy, cannot sustain the challenges that loom. An urgent and meaningful change of course has become vital before irremediable damage is accrued.

The writer is a political and security strategist and the founder of the Regional Peace Institute. He is a former special assistant to former PM Imran Khan and heads the PTI’s policy think-tank. He tweets @RaoofHasan

Disclaimer: The viewpoints expressed in this piece are the writer’s own and don’t necessarily reflect Geo.tv’s editorial policy.

Entertainment

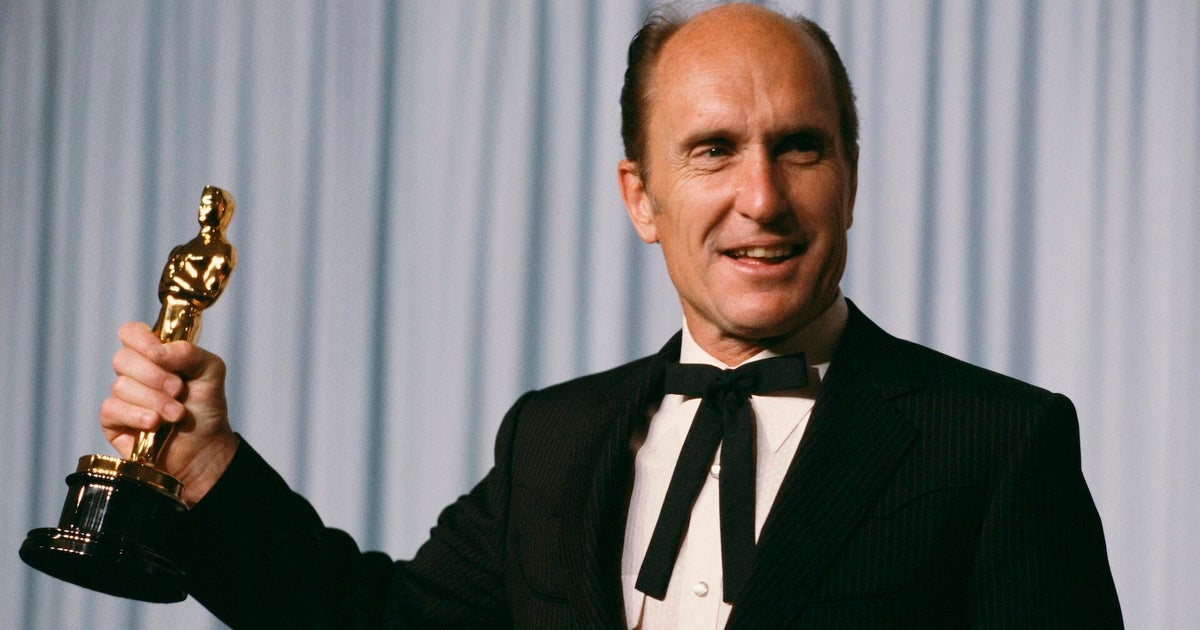

Robert Duvall, known for his roles in "The Godfather" and "Apocalypse Now," dies at 95

Oscar-winning actor Robert Duvall died on Sunday at the age of 95. Duvall starred in classics like “The Godfather” and “Apocalypse Now.” Vladimir Duthiers looks back at his career.

Source link

Entertainment

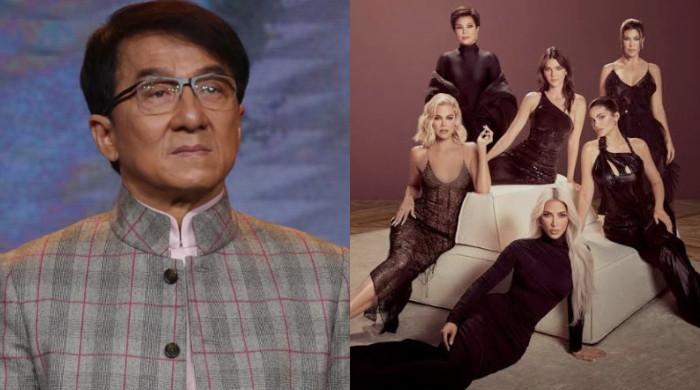

Jackie Chan left baffled when asked about the ‘Kardashians’

Jackie Chan is clueless about the Kardashians and fans are not surprised by the revelation at all.

A throwback video has resurfaced on the internet, where Jackie was asked to name his favourite Kardashian and he was completely confused.

The incident occurred in 2017, while he was promoting his film The Foreigner on Access Hollywood Live.

The host asked him, “Who is you favourite Kardashian”. Chan, who was totally perplexed, replied, “Kardashian? What do you mean, Kardashian?”

The Rush Hour actor even inquired “if the name was English”.

Fans are not surprised at all by Chan being clueless about the popular American media and business dynasty, led by Kris Jenner as they emphasized that both belong to “different worlds.”

“Jackie Chan has been making action classics for decades… Meanwhile the Kardashian family built a whole empire off reality TV. Two completely different worlds colliding”, wrote one.

Meanwhile, another one highlighted how big of a star Jackie himself is that even the Kardashians are his fan.

A social media user commented, “The truth that’s not everyone knows the kardashians and Jackie wasn’t a new school type of person He’s an icon from way back, even the Kardashians are his fans.”

Work wise, the 71-year-old Hong Kong based actor last featured in Karate Kid: Legends (2025). He is all set to return for a potential Rush Hour 4 movie.

Entertainment

Dor Brothers, Tom Cruise, Brad Pitt shake industry

Artificial intelligence has stormed into Hollywood with breathtaking speed and alarming consequences.

What began as experimental novelty has now escalated into a full-blown industry crisis, as viral AI-generated films and hyperrealistic clips of A-list actors force studios, unions, and lawmakers to confront the future of entertainment.

Earlier this week, the Dor Brothers, Berlin-based AI Video Production company, claimed they had produced a “$200,000,000 AI movie in just one day.”

The video, created entirely with generative tools, went viral on X (formerly Twitter), amassing millions of views and sparking debate over whether AI can truly replicate blockbuster filmmaking.

Supporters hailed it as proof of a new era, while skeptics dismissed it as hype.

Regardless, the post underscored how quickly AI is encroaching on traditional production models.

Deepfake Shock: Tom Cruise vs. Brad Pitt in AI combat

If the Dor Brothers’ film was a provocation, the viral AI fight sequence between Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt was a shockwave.

Created with Seedance 2.0, the 15-second clip depicted the two megastars trading blows on a rooftop with uncanny realism.

Variations of the video circulated online, complete with dialogue and camera angles, leaving audiences unsettled.

Screenwriter Rhett Reese (Deadpool & Wolverine) warned bluntly, “It’s likely over for us.”

The clip crystallized Hollywood’s worst fears that AI could convincingly mimic actors without their consent, eroding both creative integrity and livelihoods.

SAG-AFTRA draws line on AI exploitation

In response, SAG-AFTRA has taken a hard line.

The union condemned Seedance 2.0’s use of actors’ likenesses as “blatant infringement” and called for an outright ban on AI creations featuring real movie stars.

It is argued that unauthorized replication of voices and faces undermines performers’ ability to earn a living and strips them of control over their identities.

The guild has worked for several years on AI protections, with demands for strict consent requirements, compensation frameworks and federal safeguards.

Hollywood Divided: Threat or opportunity?

Hollywood is now split between alarm and opportunity.

Unions, screenwriters, and many actors see AI as an existential threat.

They warn of job losses, creative theft and a collapse of artistic value if studios embrace AI without regulation.

Some studios and technologists argue AI can be a powerful tool if used responsibly for previsualization, special effects, or enhancing workflows.

They stress that AI is not yet capable of producing true 4K theatrical-quality films, highlighting its current limitations.

The Road Ahead: 2026 as a defining year for cinema

2026 is shaping up as a pivotal year.

With studios investing billions in AI, unions mobilizing for protection, and viral clips eroding trust, Hollywood faces a defining choice: embrace AI intelligently or risk chaos.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoAye Finance IPO Day 2: GMP Remains Zero; Apply Or Not? Check Price, GMP, Financials, Recommendations

-

Fashion7 days ago

Fashion7 days agoComment: Tariffs, capacity and timing reshape sourcing decisions

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoRemoving barriers to tech careers

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week ago‘Harry Potter’ star David Thewlis doesn’t want you to ask him THIS question

-

Fashion1 week ago

Fashion1 week agoADB commits $30 mn to support MSMEs in Philippines

-

Fashion4 days ago

Fashion4 days ago$10→ $12.10 FOB: The real price of zero-duty apparel

-

Fashion1 week ago

Fashion1 week agoSaint Laurent retains top spot as hottest brand in Q4 2025 Lyst Index

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoWinter Olympics opening ceremony host sparks fury for misidentifying Mariah Carey, other blunders