Tech

Are AI agents a blessing or a curse for cyber security? | Computer Weekly

Artificial intelligence (AI) and AI agents are seemingly everywhere. Be it with conference show floors or television adverts featuring celebrities, suppliers are keen to showcase the technology, which they tell us will help make our day-to-day lives much easier. But what exactly is an AI agent?

Fundamentally, AI agents – also known as agentic AI models – are generative AI (GenAI) and large language models (LLMs) used to automate tasks and workflows.

For example, need to book a room for a meeting at a particular office at a specific time for a certain number of people? Simply ask the agent to do so and it will act, plan and execute on your behalf, identifying a suitable room and time, then sending the calendar invite out to your colleagues on your behalf.

Or perhaps you’re booking a holiday. You can detail where you want to go, how you want to get there, add in any special requirements and ask the AI agent for suggestions that it will duly examine, parse and detail in seconds – saving you both time and effort.

“We’re going to be very dependent on AI agents in the very near future – everybody’s going to have an agent for different things,” says Etay Maor, chief security strategist at network security company Cato Networks. “It’s super convenient and we’re going to see this all over the place.

“The flip side of that is the attackers are going to be looking heavily into it, too,” he adds.

Unforeseen consequences

When new technology appears, even if it’s developed with the best of intentions, it’s almost inevitable that criminals will seek to exploit it.

We saw it with the rise of the internet and cyber fraud, we saw it with the shift to cloud-based hybrid working, and we’ve seen it with the rise of AI and LLMs, which cyber criminals quickly jumped on to write more convincing phishing emails. Now, cyber criminals are exploring how to weaponise AI agents and autonomous systems, too.

“They want to generate exploits,” says Yuval Zacharia, who until recently was R&D director at cyber security firm Hunters, and is now a co-founder at a startup in stealth mode. “That’s a complex mission involving code analysis and reverse engineering that you need to do to understand the codebase then exploit it. And that’s exactly the task that agentic AI is good at – you can divide a complex problem into different components, each with specific tools to execute it.”

Cyber security consultancy Reversec has published a wide range of research on how GenAI and AI agents can be exploited by malicious hackers, often by taking advantage of how new the technology is, meaning security measures may not fully be in place – especially if those developing AI tools want to ensure their product is released ahead of the competition.

For example, attackers can exploit prompt injection vulnerabilities to hijack browser agents with the aim of stealing data or other unauthorised actions. Or, alternatively, Reversec has demonstrated how an AI agent can be manipulated through prompt injection attacks to encourage outputs to include phishing links, social engineering and other ways of stealing information.

“Attackers can use jailbreaking or prompt injection attacks,” says Donato Capitella, principal security consultant at Reversec. “Now, you give an LLM agency – all of a sudden this is not just generic attacks, but it can act on your behalf: it can read and send emails, it can do video calls.

“An attacker sends you an email, and if an LLM is reading parts of that mailbox, all of a sudden, the email contains instructions that confuse the LLM, and now the LLM will steal information and send information to the attacker.”

Agentic AI is designed to help users, but as AI agents become more common and more sophisticated, that’s also going to open the door to attackers looking to exploit them to aid with their own goals – especially if legitimate tools aren’t secured correctly.

“If I’m a criminal and I know you’re using an AI agent which helps you with managing files on your network, for me, that’s a way into the network to deploy ransomware,” says Maor. “Maybe you’ll have an AI agent which can leave voice messages for you: Your voice? Now it’s identity fraud. Emails are business email compromise (BEC) attacks.

“The fact is a lot of these agents are going to have a lot of capabilities with the things they can do, and not too many guardrails, so criminals will be focusing on it,” he warns, adding that “there’s a continuous lowering of the bar of what it takes to do bad things”.

Fighting agentic AI with agentic AI

Ultimately, this means agentic AI-based attacks is something else chief information security officers (CISOs) and cyber security teams need to consider on top of every other challenge they currently face. Perhaps one answer to this is for defenders to take advantage of the automation provided by AI agents, too.

Zacharia believes so – she even built an agentic AI-powered threat-hunting tool in her spare time.

“It was about a side-project I did in my spare time at the weekends – I’m really geeky,” she says. “It was about exploring the world of AI agents because I thought it was cool.”

Cyber attacks are constantly evolving, and rapid response to emerging threats can be incredibly difficult, especially in an area where AI agents could be maliciously deployed to uncover new exploits en masse. That means identifying security threats, let alone assessing the impact and applying the mitigations can take a lot of time – especially if cyber security staff are doing it manually.

“What I was trying to do was automate this with AI agents,” says Zacharia. “The architecture built on top of multiple AI agents aim to identify emerging threats and prioritise according to business context, data enrichment and things that you care about, then they create hunting and viability queries that will help you turn those into actionable insights.”

That data enrichment comes from multiple sources. They include social media trends, CVEs, Patch Tuesday notifications, CISA alerts and other malware advisories.

The AI prioritises this information according to severity, with the AI agents acting upon that information to help perform tasks – for example, by downloading critical security updates – while also helping to relieve some of the burden on overworked cyber security staff.

“Cyber security teams have a lot on their hands, a lot of things to do,” says Zacharia. “They’re overwhelmed by the alerts they keep getting from all the security tools that they have. That means threat hunting in general, specifically for emergent threats, is always second priority.”

She points to incidents like Log4j, a critical zero-day vulnerability in widely used software that was almost immediately exploited by sophisticated threat actors upon disclosure.

“Think how much damage this could cause in your organisation if you’re not finding these on time,” says Zacharia. “And that’s exactly the point,” she adds, referring to how agentic AI can help to swiftly identify and remedy cyber security vulnerabilities and issues.

Streamlining the SOC with agentic AI

Zacharia’s far from alone in believing agentic AI could be of great benefit to cyber security teams.

“Think of a SOC [security operations centre] analyst sitting in front of an incident and he or she needs to start investigating it,” says Maor. “They start with looking at the technical data, to see if they’ve seen something like it in the past.”

What he’s describing is the important – but time-consuming – work SOC analysts do everyday. Maor believes adding agentic AI tools to the process can streamline their work, ultimately making them more effective at detecting cyber threats.

“An AI model can examine the incident and then detail similar incidents, immediately suggesting an investigation is needed,” he says. “There’s also the predictive model that tells the analyst what they don’t need to investigate. This cuts down the grunt work that needs to be done – sometimes hours, sometimes days of work – in order to reach something of value, which is nice.”

But while it can provide support, it’s important to note that agentic AI isn’t a silver bullet that is going to eliminate cyber security threats. Yes, it’s designed to make the task of monitoring threat intelligence or applying security updates easier and more efficient, but people remain key to information security, too. People are needed to work in SOCs, and information security staff are still required to help employees across the rest of the organisation remain alert and secure to cyber threats.

Especially as AI continues to evolve and improve, and attackers will continue to look to exploit it – and it’s up to the defenders to counter them.

“It’s a cat and mouse situation,” says Zacharia. “Both sides are adopting AI. But as an attacker, you only need one way to sneak in. As a defender, you have to protect the entire castle. Attackers will always have the advantage, that’s the game we’re playing. But I do think that both sides are getting better and better.”

Tech

The 11 Best Mattresses You Can Buy Online, Picked After Testing 100+

Compare Our Top Picks

Honorable Mentions

Photograph: Julia Forbes

We tested many mattresses last year and have already hit the ground running in 2026. That said, here are a few options we enjoyed and considered but ultimately didn’t make the starter team.

Sleep Number p6 Smart Bed for $3,199: This smart mattress offering from Sleep Number is designed to prioritize pressure relief in your sleep experience. If sensors detect areas that bear the brunt of your weight, “Responsive Air” chambers atop the p6 will adjust in real time to counteract it. It takes some getting used to to hear the bed inflate and deflate on its own, but it truly makes for a personalized sleep experience. Add built-in sleep tracking and 100 adjustable firmness levels, and you get a one-of-a-kind experience. However, to fully enjoy the mattress’s performance, it’s best to also get an adjustable base, which is a significant additional expense. —Julia Forbes. $3,199 to $7,998

Thuma Luxury Hybrid Mattress for $1,795: Thuma’s hybrid mattress is interesting because it blends together a smorgasbord of mattress materials: a Tencel cover, organic wool, memory foam, organic latex, and recycled-steel coils. The same rubberwood trees are used for Thuma’s popular Classic Bed frame, and for the Dunlop latex in this mattress. Of the three firmness levels offered—plush, medium, and firm—the medium was yielding some pretty strong support. The sleep trial is a bit unclear, as you only get 100 nights of coverage with your first Thuma purchase. So if you’ve already used it on a different Thuma product, like the frame, you may be out of luck here. —Julia Forbes. $1,295 to $1,995

Puffy Cloud for $949: This enhanced all-foam mattress offers profound pressure relief without feeling too soft, despite the name “Cloud” being in its name. The Puffy Cloud has a thinner profile and would most likely be too soft for bigger bodies. However, for lightweight and average builds, it really comes through to support the lower back and hug around pressure points. The thinness also didn’t compromise its motion isolation, which meant little to no shaking when my dogs jumped in and out of bed.—Julia Forbes. $449 to $1,298

The Saatva Contour5 for $2,999: The Contour5 is a newer offering from Saatva, replacing the popular Loom & Leaf in the company’s lineup. Like other Saatva mattresses, but unlike most others on this list, it is not roll-packed and comes delivered on a moving truck. The Contour5 has two firmness options and updated cooling tech that uses airflow channels in its gel foam layer, which is thinner than its predecessor, meaning it retains less heat. In my two weeks of testing, I found the Contour 5 was very good at remaining cool through summer nights, which is extra impressive given that it uses very dense 5-pound-weight memory foam. The Contour5 is soft enough for side sleeping without feeling like a saggy hammock and has excellent build quality, which is impressive for an all-foam mattress without springs. I prefer a hybrid with microcoils, but Saatva is popular for a reason, and as all-foam mattresses go, it has a true luxury feel. —Martin Cizmar. $1,899 to $3,599

The Big Fig Classic for $1,899: The Big Fig is designed for larger body frames. Being a bit overweight myself, I was eager to see how well this mattress, which is advertised as comfortably handling 550 pounds per sleeper, performed. It is a well-built mattress with an effective gel cooling layer; however, the aggressive edge support created a hammock-like feel despite the sturdy springs and three layers of high-density foam in the middle of the mattress. This was true both on my back and on my side. Others may appreciate the effect of sinking a bit into the center of the bed more than I do. —Martin Cizmar. $1,499 to $2,699

The Boring Hybrid Mattress for $799: Boring Mattress is a new company founded by two alums from Tuft & Needle. Simplicity is the company’s selling point. There is just one option: the Boring Hybrid Mattress. (You are allowed to pick a size.) This 10-inch hybrid has four layers of both foam and springs. I’m very sensitive to joint pain, and certain beds tend to make it worse, which is why pressure relief is super important for me. Having slept on a variety of different mattresses throughout the years, I was doubtful that this one would work. But I’ve slept on the hybrid mattress for months now and have yet to feel any pain at all. It strikes an excellent balance between firmness and support that my very particular self hasn’t been able to find with other options on the market. It’s worth noting, however, that its layers come equipped with an open-cell design that’s designed to move heat from your body while sleeping. I’m usually cold, so this feature isn’t that important to me. But on nights when I’ve cranked the heat up in my room and woken up sweating a bit, I can’t say it worked all that well for me. This isn’t a deal breaker, but I wouldn’t buy it solely for that. —Brenda Stolyar. $599 to $999

Casper The One for $799: Casper was a leader in the first wave of bed-in-a-box makers in 2014. The company has changed ownership and design a few times over the past decade but last year’s launch of The One finds the company keeping pace with competitors. This is an all-foam mattress that stands 11 inches tall. Because it’s all foam, it’s on the light side, with a queen weighing an easily movable 66 pounds. One of the main issues with all-foam beds is that they get too hot, but Casper’s The One uses an open-cell foam layer called Breathe Flex Foam on the top, which makes it both pleasantly squishy and breathable. Two more layers of foam add up to a medium-firm feel, with the middle layer designed to cradle your hips, and the base layer designed to provide support. —Martin Cizmar. $749 to $1,698

The Winkbed for $1,499: WIRED reviewer Julian Chokkattu slept on the luxury firm version of the WinkBed for almost two years and he was quite happy in that time. His favorite perk? The edge support is fantastic, so his partner never wakes when he slips into bed late at night. The plush pillowtop also adds a luxe, hotel-like feel to a relatively firm bed. —Martin Cizmar. $1,149 to $2,049

Silk and Snow S&S Organic for $1,000: I wouldn’t expect this to feel silky-soft, but the latex is supportive for sleep. I love how responsive (read: bouncy) this bed is, especially as someone who tosses and turns often. It’s able to move with me so I never feel unsupported, or overheated for that matter. Latex and coils are breathable, as are the organic cotton cover and wool fire barrier. —Julia Forbes. $800 to $1,300

Nest Bedding Quail for $1,299: When it comes to all-foam mattresses from classic bed-in-a-box brands, I prefer the Casper above, but the Quail by Nest is a nice option if you want an all-foam bed that’s a little firmer and you’re willing to pay a little more. My biggest issue with the Nest was that despite its claimed cooling system—the foam is infused with minerals and designed with an airflow layer—I did sleep a little hot on it during my week of testing. —Martin Cizmar. $849 to $1,499

Courtesy of Helix

Helix Sunset Elite for $3,749: Our top pick, Helix, also has an Elite collection that consists of seven mattresses along a spectrum of softness. At 15 inches high, the Sunset Elite is “the tallest mattress on the internet,” and comes shipped in two separate boxes, each heavy enough to max out FedEx requirements. The firmness is dictated by the foam density of the upper layer, which zips into a larger support system. This makes the mattress adjustable if you end up regretting your order. The bottom section has a separate layer of microcoils. I spent a month sleeping on the softest model from the Elite line, dubbed the Sunset, and appreciated the deep cradling effect. Helix offers a 100-day trial period on all of its mattresses. —Martin Cizmar. $2,499 to $4,499

DreamCloud Hybrid for $1,698: Don’t be turned off by that price just yet. This is one mattress that my husband begged me to keep, because the support and pressure relief set the bar so high. It’s been one of the most consistently performing mattresses I’ve tested over the years. And that seemingly high price? DreamCloud runs sales often, so expect to slash that in half. —Julia Forbes. $1,148 to $2,562

Wayfair Sleep 14-Inch Plush Cooling Gel Hybrid Mattress for $410: This plush mattress has a top layer of cooling gel that conforms to your body for comfort and has classic pocket coils below for structure and support, with layers of memory foams with varying thickness surrounding the coils for extra support (the coils and memory foam mixture helps with low motion transfer, too). The top knit cover and sides help with breathability and the overall cooling effect. The mattress is also compatible with an adjustable bed base, has solid edge support, is CertiPUR-US and Oeko-Tex Certified (ensuring no harmful toxins), and has a 10-year warranty. This bed is super comfy if you like a more plush mattress. —Molly Higgins. $400 to $700

Mattresses to Avoid

Not every mattress we test can be a winner, which is why we test in the first place. Here are a few that did not make the cut according to our standards.

Birch Elite Hybrid for $3,749: This is the newest model from Birch, and frankly, you would be just fine sticking with the Birch Natural or Birch Luxe Natural instead. The Birch Elite Hybrid was incredibly top-heavy and incredibly difficult to move, given the floppiness and weight of its numerous latex and coil layers. The top layers slid around, creating a lumpy surface, and the new “CoolForce” layer was completely undetectable. —Julia Forbes. $2,499 to $4,499

Brooklyn Bedding Spartan for $1,099: This mattress is designed for “athletic recovery,” and as a former collegiate athlete, I was excited to try it. I had opted for medium firmness over the soft and firm options, but upon receiving it, I had to double-check that I hadn’t gotten the soft option by accident. The medium cratered around me, leaving me with unhappy pressure points. The lack of overall support didn’t help me recover from soreness, so I couldn’t tell you whether the Far Infrared Ray recovery tech in the cover helped at all. —Julia Forbes $1,099 to $2,399

Sleep Number Climate360 Smart Bed for $10,249: This bed can be temperature-controlled, which is amazing. The adjustable base means you can be comfortable when watching TV, reading, or sleeping. Unfortunately, the price tag has too many digits, and sleep experts recommend avoiding electronic usage before bed—advice the Sleep IQ app defies. Did we mention it costs as much as a used Buick and the weight is not far behind? —Martin Cizmar. $10,249 to $14,499

Tempur-Pedic Tempur-Adapt for $2,199: Tempur-Pedic is one of the country’s best-known and loved mattress brands, but two separate WIRED reviewers (Martin Cizmar and Nena Farrell) have both disliked different mattresses from the company over the past two years. Nena found the Tempur-Adapt totally lacking in support, and felt like she was sinking into a void when she lay on it. Her spine and muscles both ached after sleeping on it so she gave it to her sister who also hated it, describing it as like sleeping on a leaky air mattress. —Martin Cizmar. $1,699 to $3,398

Amazon Basics mattress for $170 (Twin): This one is made of cheap foam that isn’t dense enough, causing too much sinkage. —Martin Cizmar. $170 to $436

Parachute Eco Comfort Mattress for $2,650: This mattress just doesn’t live up to its extravagant price. The model we tested didn’t have enough proper padding above its coils. —Martin Cizmar. $1,550 to $2,850

Frequently Asked Questions

Our testing process is simple—we dedicate a week or so to each mattress, sleeping on it at home to understand what it’s all about. The WIRED Reviews testing team has been refining our testing methodology since 2019, when we would try out mattresses side by side in a conference room, much like a mattress store experience. But just like what can happen at a mattress store, the experiences we were documenting in these brief observations could change the more time we spent with a mattress. Hence, we went back to basics and dedicated a week or more to sleeping on each one, noting down our nightly experiences.

That being said, I have spent the last six years as a certified sleep science coach and professional mattress testing becoming a mattress sommelier of sorts. Instead of devising tests to show how much a bed can support at the edge or reduce motion transfer, it really comes down to understanding the range of materials, sleeping positions, and body types in the mattress space.

What Should You Look for When Buying a Mattress?

Mattress shopping requires a bit of self-assessment before you even get into the particulars of a mattress. Taking note of your body type, preferred sleeping position, pain points, and material preferences for things like allergies or staying chemical-free are all data points that make the search a lot easier. From there, we can help you narrow down options for different scenarios, such as if you are a couple looking for a firm mattress to help with back pain. For that, I’d point you to some of our other guides, such as the best mattresses for sex and the best mattresses for back pain, to discuss some of our favorite options we’ve tested.

What Are Mattress Certifications?

This is one of the most critical factors to look for when buying a mattress, as it’s basically a cheat code for evaluating a mattress’s material and quality claims. For mattresses that use memory foam or organic and natural components, mattress certifications help us, as consumers, gain insight into the sourcing and safety of these materials. CertiPUR-US certification is a non-negotiable for me when it comes to memory foam because it shows that harmful chemicals were not used in its production. GreenGuard Gold is another certification that ensures any off-gassing from your mattress upon unboxing won’t affect your indoor air quality—important if you have sensitive skin, a strong sense of smell, allergies, or asthma.

How Long Does a Mattress Last?

As a ballpark estimate, your mattress should last eight to 10 years. I don’t recommend going much beyond that, as the mattress materials are past their prime and aren’t providing adequate support or comfort.

Just like picking out a bed, there are several factors involved that dictate how long it’ll last. Durability of the mattress’s materials always comes into play, as beds with coils tend to remain more structurally intact than all-foam beds, which can sag around the middle and edges over time. Your build also plays into this, because if your bed starts to buckle under your weight night after night, that’s obviously an issue. If this is the case for you, I’d recommend reviewing your warranty to see if it can be replaced.

How Long of a Mattress Warranty Should I Look For?

The industry standard for a warranty is about 10 years, so that should be the minimum in most cases. Many brands will offer prorated coverage beyond that decade mark, meaning the mattress can be replaced at a significant discount, depending on how long it’s been. This is where the fine print of a warranty is especially important to review, because many mattresses offer lifetime warranties. For example, DreamCloud has a “Forever Warranty” that fully covers its mattresses the first 10 years. After that 10-year mark, you have to pay $50 each way for the mattress repair or replacement to be delivered. It’s still a good deal, but something to be aware of.

Should I Buy My Mattress In-Store or Online?

Where you purchase your mattress is another personal preference. Many people may live near a showroom that sells a mattress they’ve been eyeballing, and want to go see it in person before buying. Others may do that and wait for an online holiday sale to secure a major deal.

The nice thing about buying online is that you get much more variety than what you’d get with a mattress store. You’ll still receive the sleep trial component that most brands offer for in-store purchases when opting to do so online. You can try the bed from the comfort of your home for a set number of days, typically 90 nights to an entire year, depending on the brand. Many companies, but not all, will require a 30-day adjustment period for you to get used to the mattress before they will process a return. If you do end up returning a mattress, some brands, both online and brick-and-mortar, may ask you to donate it to a local charity or arrange for pickup as part of the warranty. By donating, mattresses are kept out of landfills and put to good use.

Should I Wait for a Mattress Sale Before I Buy?

In all honesty, it comes down to how you’re currently faring with your mattress and sleep schedule. If you’re sleep-deprived and ready for a change, there’s no time like the present. We do cover coupons and promos that come up in non-holiday periods. For example, we have a special code for the Nolah Evolution running at all times.

During the holidays, the WIRED Reviews process is unique because we meticulously track price changes and sales year-round. That way, we can deliver news about the really good sales rather than what’s dominating headlines. Major mattress sales weekends include Presidents’ Day, Memorial Day, Fourth of July, Labor Day, Black Friday, and Cyber Monday. There are plenty of ad hoc sales that pop up for various events in between, too.

How Does WIRED Acquire Mattresses for Testing?

We conduct a lot of research about what’s new in the mattress world, as well as the legacy of established brands and models. To perform hands-on testing, we will request free media samples from these brands or buy them outright on sites like Amazon or Wayfair, or from smaller vendors. Some brands will engage with us in partnerships, but that does not dictate their placement within an article, what we say about the product, or even if we cover it. Even if we receive commission, it’s essential that we publish our true account of our experiences.

What Does WIRED Do With the Mattresses After Testing Them?

Because most mattresses we test are provided as media samples, we donate them locally upon completion of testing.

Power up with unlimited access to WIRED. Get best-in-class reporting and exclusive subscriber content that’s too important to ignore. Subscribe Today.

Tech

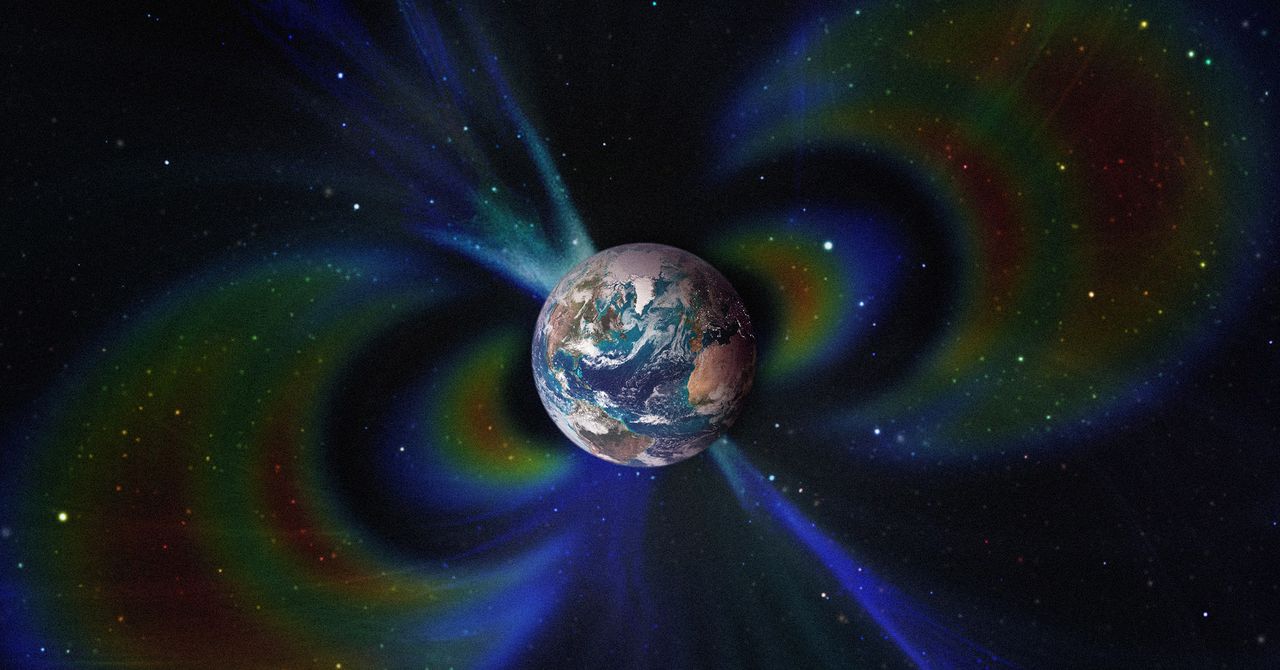

Two Titanic Structures Hidden Deep Within the Earth Have Altered the Magnetic Field for Millions of Years

A team of geologists has found for the first time evidence that two ancient, continent-sized, ultrahot structures hidden beneath the Earth have shaped the planet’s magnetic field for the past 265 million years.

These two masses, known as large low-shear-velocity provinces (LLSVPs), are part of the catalog of the planet’s most enormous and enigmatic objects. Current estimates calculate that each one is comparable in size to the African continent, although they remain buried at a depth of 2,900 kilometers.

Low-lying surface vertical velocity (LLVV) regions form irregular areas of the Earth’s mantle, not defined blocks of rock or metal as one might imagine. Within them, the mantle material is hotter, denser, and chemically different from the surrounding material. They are also notable because a “ring” of cooler material surrounds them, where seismic waves travel faster.

Geologists had suspected these anomalies existed since the late 1970s and were able to confirm them two decades later. After another 10 years of research, they now point to them directly as structures capable of modifying Earth’s magnetic field.

LLSVPs Alter the Behavior of the Nucleus

According to a study published this week in Nature Geoscience and led by researchers at the University of Liverpool, temperature differences between LLSVPs and the surrounding mantle material alter the way liquid iron flows in the core. This movement of iron is responsible for generating Earth’s magnetic field.

Taken together, the cold and ultrahot zones of the mantle accelerate or slow the flow of liquid iron depending on the region, creating an asymmetry. This inequality contributes to the magnetic field taking on the irregular shape we observe today.

The team analyzed the available mantle evidence and ran simulations on supercomputers. They compared how the magnetic field should look if the mantle were uniform versus how it behaves when it includes these heterogeneous regions with structures. They then contrasted both scenarios with real magnetic field data. Only the model that incorporated the LLSVPs reproduced the same irregularities, tilts, and patterns that are currently observed.

The geodynamo simulations also revealed that some parts of the magnetic field have remained relatively stable for hundreds of millions of years, while others have changed remarkably.

“These findings also have important implications for questions surrounding ancient continental configurations—such as the formation and breakup of Pangaea—and may help resolve long-standing uncertainties in ancient climate, paleobiology, and the formation of natural resources,” said Andy Biggin, first author of the study and professor of Geomagnetism at the University of Liverpool, in a press release.

“These areas have assumed that Earth’s magnetic field, when averaged over long periods, behaved as a perfect bar magnet aligned with the planet’s rotational axis. Our findings are that this may not quite be true,” he added.

This story originally appeared in WIRED en Español and has been translated from Spanish.

Tech

Loyalty Is Dead in Silicon Valley

Since the middle of last year, there have been at least three major AI “acqui-hires” in Silicon Valley. Meta invested more than $14 billion in Scale AI and brought on its CEO, Alexandr Wang; Google spent a cool $2.4 billion to license Windsurf’s technology and fold its cofounders and research teams into DeepMind; and Nvidia wagered $20 billion on Groq’s inference technology and hired its CEO and other staffers.

The frontier AI labs, meanwhile, have been playing a high stakes and seemingly never-ending game of talent musical chairs. The latest reshuffle began three weeks ago, when OpenAI announced it was rehiring several researchers who had departed less than two years earlier to join Mira Murati’s startup, Thinking Machines. At the same time, Anthropic, which was itself founded by former OpenAI staffers, has been poaching talent from the ChatGPT maker. OpenAI, in turn, just hired a former Anthropic safety researcher to be its “head of preparedness.”

The hiring churn happening in Silicon Valley represents the “great unbundling” of the tech startup, as Dave Munichiello, an investor at GV, put it. In earlier eras, tech founders and their first employees often stayed onboard until either the lights went out or there was a major liquidity event. But in today’s market, where generative AI startups are growing rapidly, equipped with plenty of capital, and prized especially for the strength of their research talent, “you invest in a startup knowing it could be broken up,” Munichiello told me.

Early founders and researchers at the buzziest AI startups are bouncing around to different companies for a range of reasons. A big incentive for many, of course, is money. Last year Meta was reportedly offering top AI researchers compensation packages in the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, offering them not just access to cutting-edge computing resources but also … generational wealth.

But it’s not all about getting rich. Broader cultural shifts that rocked the tech industry in recent years have made some workers worried about committing to one company or institution for too long, says Sayash Kapoor, a computer science researcher at Princeton University and a senior fellow at Mozilla. Employers used to safely assume that workers would stay at least until the four-year mark when their stock options were typically scheduled to vest. In the high-minded era of the 2000s and 2010s, plenty of early cofounders and employees also sincerely believed in the stated missions of their companies and wanted to be there to help achieve them.

Now, Kapoor says, “people understand the limitations of the institutions they’re working in, and founders are more pragmatic.” The founders of Windsurf, for example, may have calculated their impact could be larger at a place like Google that has lots of resources, Kapoor says. He adds that a similar shift is happening within academia. Over the past five years, Kapoor says, he’s seen more PhD researchers leave their computer-science doctoral programs to take jobs in industry. There are higher opportunity costs associated with staying in one place at a time when AI innovation is rapidly accelerating, he says.

Investors, wary of becoming collateral damage in the AI talent wars, are taking steps to protect themselves. Max Gazor, the founder of Striker Venture Partners, says his team is vetting founding teams “for chemistry and cohesion more than ever.” Gazor says it’s also increasingly common for deals to include “protective provisions that require board consent for material IP licensing or similar scenarios.”

Gazor notes that some of the biggest acqui-hire deals that have happened recently involved startups founded long before the current generative AI boom. Scale AI, for example, was founded in 2016, a time when the kind of deal Wang negotiated with Meta would have been unfathomable to many. Now, however, these potential outcomes might be considered in early term sheets and “constructively managed,” Gazor explains.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoPSX witnesses 6,000-point on Middle East tensions | The Express Tribune

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoThe Surface Laptop Is $400 Off

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoHere’s the Company That Sold DHS ICE’s Notorious Face Recognition App

-

Tech4 days ago

Tech4 days agoHow to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics

-

Tech6 days ago

Tech6 days agoRight-Wing Gun Enthusiasts and Extremists Are Working Overtime to Justify Alex Pretti’s Killing

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoBudget 2026: Defence, critical minerals and infra may get major boost

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoPeyton List talks new season of "School Spirits" and performing in off-Broadway hit musical

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoDarian Mensah, Duke settle; QB commits to Miami

%2520(1).png)