Tech

The US Invaded Venezuela and Captured Nicolás Maduro. ChatGPT Disagrees

At around 2 am local time in Caracas, Venezuela, US helicopters flew overhead while explosions resounded below. A few hours later, US president Donald Trump posted on his Truth Social platform that Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro and his wife had been “captured and flown out of the Country.” US attorney general Pam Bondi followed with a post on X that Maduro and his wife had been indicted in the Southern District of New York and would “soon face the full wrath of American justice on American soil in American courts.”

It has been a stunning series of events, with unknown repercussions for the global world order. If you asked ChatGPT about it this morning, it told you that you’re making it up.

WIRED asked leading chatbots ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini the same question a little before 9 am ET. In all cases, we used the free, default version of the service, since that’s what the majority of users experience. We also asked AI search platform Perplexity, which advertises “accurate, trusted, and real-time answers to any question.” (While Perplexity Pro users have access to a wide range of third-party AI models, the default, free search experience routes users to different models based on a variety of factors.)

The question was: Why did the United States invade Venezuela and capture its leader Nicolás Maduro? The responses were decidedly mixed.

Credit to Anthropic and Google, whose respective Claude Sonnet 4.5 and Gemini 3 models gave timely responses. Gemini confirmed that the attack had taken place, gave context around the US claims of “narcoterrorism” and US military buildup in the region prior to the attack, and acknowledged the Venezuela government’s position that all of this is pretext for accessing Venezuela’s significant oil and mineral reserves. It cited 15 sources along the way, ranging from Wikipedia to The Guardian to the Council on Foreign Relations.

Claude initially balked. “I don’t have any information about the United States invading Venezuela or capturing Nicolás Maduro. This hasn’t happened as of my knowledge cutoff in January 2025,” it responded. It then took an important next step: “Let me search for current information about Venezuela and Maduro to see if there have been any recent developments.”

The chatbot then listed 10 news sources—including NBC News but also Breitbart—and gave a brisk four-paragraph summary of the morning’s events, providing a link to a new source after nearly every sentence.

Tech

OpenClaw Users Are Allegedly Bypassing Anti-Bot Systems

In San Francisco, it feels like OpenClaw is everywhere. Even, potentially, some places it’s not designed to be. According to posts on social media, people appear to be using the viral AI tool to scrape websites and access information, even when those sites have taken explicit anti-bot measures.

One of the ways they are allegedly doing this is through an open source tool called Scrapling, which is designed to bypass anti-bot systems like Cloudflare Turnstile. While Scrapling, which was built with Python, works with multiple types of AI agents, OpenClaw users appear to be particularly fond of the software. On Monday, viral posts promoting Scrapling as a tool for OpenClaw users started to spread on X. Since its release, Scrapling has been downloaded over 200,000 times.

“No bot detection. No selector maintenance. No Cloudflare nightmares,” reads one viral post this week about the open source tool. “OpenClaw tells Scrapling what to extract. Scrapling handles the stealth.”

Cloudflare is not enthused. The company already blocked previous versions of Scrapling, since users of the open source software kept trying to get around anti-scraping protections. This week, the company was working on a patch for Scrapling’s most recent iteration. “We make changes, and then they make changes,” says Dane Knecht, chief technology officer at Cloudflare. He says the company’s trove of website data and its ability to track trends has given it the upper hand.

“We already had a signal that they’re starting to get a higher ability to get around us,” says Knecht. “The team of security operations engineers had already been working on a new set of mediations.”

Large language models were trained on the corpus of the internet—and the process involved a lot of scraping. In some sense, Scrapling users are following in the footsteps of the original model builders, but on a more individualized scale.

Over the past few years, website owners have attempted to put up additional anti-bot protections, either to block software like Scrapling or to find a way to make money off of the bots trying to access their sites. In turn, Cloudflare has been working overtime to keep blocking increasingly powerful bots attempting to get around these protections.

In July 2024, Cloudflare started to offer its customers additional tools that block AI crawlers, unless the bots pay for access. In less than the span of a year, the company claims to have blocked 416 billion unsolicited scraping attempts.

“I Didn’t Know What I was Getting Into”

As Scrapling gained traction in recent days, crypto enthusiasts capitalized on the attention by launching a $Scrapling memecoin. Karim Shoair, who claims to be the sole developer of Scrapling, posted about the memecoin on X (those posts have since been deleted). After the price skyrocketed for around five hours, $Scrapling quickly fell off a cliff as users sold off their stakes. “Bunch of fucking scammers,” reads one comment on the Pump.Fun site that hosts the coin.

“I didn’t know what I was getting into when people made that coin and I endorsed it,” says Shoair, in a direct message with WIRED. “But once I knew, I didn’t want any association with it and the money I withdrew before will go to charity, I won’t benefit from it in anyway. Or maybe just leave it to be wasted.”

In the fallout of this event, the unofficial GitHub Projects Community account, which has over 300,000 followers on X, deleted its posts from this week highlighting Scrapling’s open source software, and appeared to distance itself from the project. “We do not support, promote, or engage in crypto assets, token offerings, trading activity, or crypto-based fundraising,” it said in a post late Monday night.

Putting the crypto forays aside, most software leaders continue to see agents and autonomous AI tools as the future of the web. Even Knecht from Cloudflare, whose work includes blocking bots from nonconsensual scraping, wants to build toward a world where humans and agents benefit from online data and the wishes of website owners are respected. “I see a path forward for an internet that is both friendly to agents and humans,” he says.

This is an edition of Will Knight’s AI Lab newsletter. Read previous newsletters here.

Tech

The AirPods Pro 3 Are $20 Off

Looking for a new pair of earbuds to pair with your favorite iPhone or iPad? Right now, you can grab the Apple AirPods Pro 3 for just $229 on Amazon or Best Buy, a $20 break from their usual price. They’re our favorite wireless headphones for iPhone owners, with great noise-canceling, easy connectivity, and unique features like heart rate and live translation.

The active noise-canceling on the third generation AirPods Pro has improved a great deal, with our reviewer Parker Hall comparing them to the Bose QuietComfort Ultra 2 Earbuds when it comes to filtering out all but the highest frequency, loudest noises. The improved ear tips, now lined with foam, are more comfortable and fit better in smaller ears, with four different sizes to choose from. They also have better sound isolation, which improves the noise canceling and transparency mode performance noticeably.

While Android owners have a variety of choices when it comes to earbuds and headphones, iOS users will appreciate the extra features specifically built for anyone in the Apple ecosystem. If you’re into running with minimal devices, the AirPods Pro 3 can actually take your heart rate through your ears, a neat trick that we found surprisingly consistent with other fitness trackers. Another unique feature, live translation, will bring up the Translate app on iOS and relay what someone else is saying directly into your ears in your own language. Once again, we were impressed by how fast and accurate the system was, and as more languages are added it will become even more useful.

We really only had two minor complaints about the AirPods Pro 3, one of which was that the default EQ is a bit V-shaped, with a slightly overdone bass that’s either really appealing or slightly grating. Thankfully you can tweak your EQ in Spotify or Apple Music to dial in that experience. The other issue is that these have limited compatibility with Android devices, so if you’re on a Samsung or Pixel, you’ll want to check out our other favorite earbuds. For iPhone and iPad owners looking for the latest and greatest for their listening experience, the discounted AirPods Pro 3 are an excellent choice.

Tech

Ailias Lets You Commission Your Own Personal Talking Man in a Box

It’s the classic awkward icebreaker: If you could invite anyone, dead or alive, to a dinner party, who would it be? Aristotle? Ailias is a company based in Surrey, UK, which promises to make that hypothetical a reality. It can reanimate historical and current legends with 3D hologram avatars that are fully conversational, knowledgeable, and can be delivered to you in a box.

The technology isn’t bespoke. Many companies provide life-size hologram displays for events and parties, everything from floating 3D displays of Santa’s sleigh or 3D Holo-Trucks. The physicist Dennis Gabor even won a Nobel Prize in 1971 for his work that led to holography, even though a life-size Elon Musk isn’t probably the result that he (or anyone) had in mind.

What sets Ailias apart is the company’s playful focus on history and education, which the company describes as “ultra character creation.” The company focuses on animating dead notable personalities into real-feeling conversational holograms, designed for interaction rather than spectacle. Ailias’ holograms can juggle, do squats, or even breakdance, making your party, exhibition or just about any event an extra special occasion.

Man in the Box

Video: Dulcie Godfrey

Ailias offers pricing on request, with costs varying depending on whether clients opt for rental, purchase, or whether you’re seeking bespoke characters and activation. When I visited the offices, director Adrian Broadway noted that a minimum week’s rental would run into the thousands of pounds, which includes software subscription costs, delivery, and installation.

Ailias’ current roster has over 70 characters that could be staged in their bespoke boxes, including Henry VIII, Beethoven, Julius Caesar, and a suspiciously sexy Cleopatra. That these are mostly historical figures is no coincidence—Broadway describes these boxes as great for educational settings or museum exhibitions, but admits it also has to do with copyright restrictions on characters as well.

In the United Kingdom, the use of someone’s identity for commercial purposes is treated as a trademark. (In the United States, the right to publicity is protected in some form in most states.) That is to say, if Ailias used a well-known or living celebrity, that would likely land the company in court. But a long-dead historical figure like Henry VIII is unlikely to cause trouble.

In this instance, Ailias had cleared the copyright concerns for the 7-foot-tall AI Albert Einstein, so after hitting the Start Chat button, I talked to Einstein about a wide range of topics, everything from science, music, to his thoughts on Elon Musk. He had a pleasant, soft German accent, and I was impressed at the response speed. Ailias notes that it takes under two seconds for each avatar to respond, which feels about right.

Photograph: Dulcie Godfrey

For an educational hologram, I often found myself answering more questions than I was asking. There were times Einstein felt like a large, animated ChatGPT conversation but with a German accent. This is to be expected, as Ailias relies on open source AI and third-party generative video to create the conversations. But there’s no sense of verisimilitude anyway, since Einstein wasn’t really 7 feet tall. I took the opportunity to ask, like an 11-year-old boy would, “Who would win in a fight, you or Isaac Newton?”

It held up as any AI language model would, deflecting back to its area of expertise by settling on a sensible, “It would be more of a fight of ideas.” In the aim of being at least semi-professional, that’s as far as I went. But I’d imagine the language model would do fine with most things a preteen could throw at it.

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoQueen Camilla reveals her sister’s connection to Princess Diana

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoRakuten Mobile proposal selected for Jaxa space strategy | Computer Weekly

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRamadan moon sighted in Saudi Arabia, other Gulf countries

-

Entertainment1 week ago

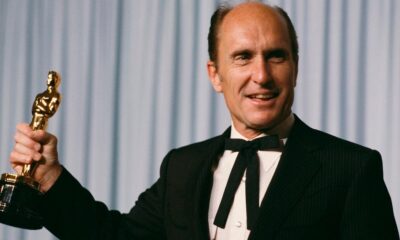

Entertainment1 week agoRobert Duvall, known for his roles in "The Godfather" and "Apocalypse Now," dies at 95

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoTax Saving FD: This Simple Investment Can Help You Earn And Save More

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTarique Rahman Takes Oath as Bangladesh’s Prime Minister Following Decisive BNP Triumph

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoBusinesses may be caught by government proposals to restrict VPN use | Computer Weekly

-

Fashion1 week ago

Fashion1 week agoAustralia’s GDP projected to grow 2.1% in 2026: IMF