Tech

Why bug bounty schemes have not led to secure software | Computer Weekly

Governments should make software companies liable for developing insecure computer code. So says Katie Moussouris, the white hat hacker and security expert who first persuaded Microsoft and the Pentagon to offer financial rewards to security researchers who found and reported serious security vulnerabilities.

Bug bounty schemes have since proliferated and have now become the norm for software companies, with some, such as Apple, offering awards of $2m or more to those who find critical security vulnerabilities.

Moussouris likens security vulnerability research to working for Uber, only with lower pay and less job security. The catch is that people only get paid if they are the first to find and report a vulnerability. Those who put in the work but get results second or third get nothing.

“Intrinsically, it is exploitative of the labour market. You are asking them to do speculative labour, and you are getting something quite valuable out of them,” she says.

Some white hat hackers, motivated by helping people fix security problems, have managed to make a living by specialising in finding medium-risk vulnerabilities that may not pay as well as the high-risk bugs, but are easier to find.

But most security researchers struggle to make a living as bug bounty hunters.

“Very few researchers are capable of finding those elite-level vulnerabilities, and very few of the ones that are capable think it is worth their while to chase a bug bounty. They would rather have a nice contract or a full-time role,” she says.

Ethical hacking comes with legal risks

Its not just the lack of a steady income. Security researchers also face legal risks from anti-hacking laws, such as the UK’s Computer Misuse Act and the US’s draconian Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

When Moussouris joined Microsoft in 2007, she persuaded the company to announce that it would not prosecute bounty hunters if they found online vulnerabilities in Microsoft products and reported them responsibly. Other software companies have since followed suit.

The UK government has now recognised the problem and promised to introduce a statutory defence for cyber security researchers who spot and share vulnerabilities to protect them from prosecution.

Another issue is that many software companies insist on security researchers signing a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) before paying them for their vulnerability disclosures.

This flies against the best practices for security disclosures, which Moussouris has championed through the International Standards Organisation (ISO).

When software companies pay the first person to discover a vulnerability a bounty in return for signing an NDA, that creates an incentive for those who find the same vulnerability to publicly disclose it, increasing the risk that a bad actor will exploit it for criminal purposes.

Worse, some companies use NDAs to keep vulnerabilities hidden but don’t take steps to fix them, says Moussouris, whose company, Luta Security, manages and advises on bug bounty and vulnerability disclosure programmes.

“We often see a big pile of unfixed bugs,” she says. “And some of these programmes are well funded by publicly traded companies that have plenty of cyber security employees, application security engineers and funding.”

Some companies appear to regard bug bounties as a replacement for secure coding and proper investment in software testing.

“We are using bug bounties as a stop-gap, as a way to potentially control the public disclosure of bugs, and we are not using them to identify symptoms that can diagnose our deeper lack of security controls,” she adds.

Ultimately, Moussouris says, governments will have to step in and change laws to make software companies liable for errors in their software, in much the same way car manufacturers are responsible for safety flaws in their vehicles.

“All governments have pretty much held off on holding software companies responsible and legally liable, because they wanted to encourage the growth of their industry,” she says. “But that has to change at a certain point, like automobiles were not highly regulated, and then seatbelts were required by law.”

AI could lead to less secure code

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) could make white hat hackers redundant altogether, but perhaps not in a way that leads to better software security.

All of the major bug bounty platforms in the US are using AI to help with the triage of vulnerabilities and to augment penetration testing.

An AI-powered penetration testing platform, XBow, recently topped the bug bounty leaderboard by using AI to focus on relatively easy-to-find vulnerabilities and testing likely candidates in a systematic way to harvest security bugs.

“Once we create the tools to train AI to make it appear to be as good, or better in a lot of cases, than humans, you are pulling the rug out of the market. And then where are we going to get the next bug bounty expert?” she asks.

The current generation of experts with the skills to spot when AI systems are missing something important is in danger of disappearing.

“Bug bounty platforms are moving towards an automated, driverless version of bug bounties, where AI agents are going to take the place of human bug hunters,” she says.

Unfortunately, it’s far easier for AI to find software bugs than it is to use AI to fix them. And companies are not investing as much as they should in using AI to mitigate security risks.

“We have to figure out how to change that equation very quickly. It is easier to find and report a bug than it is for AI to write and test a patch,” she says.

Bug bounties have failed

Moussouris, a passionate and enthusiastic advocate of bug bounty schemes, is the first to acknowledge that bug bounty schemes have, in one sense, failed.

Some things have improved. Software developers have shifted to better programming languages and frameworks that make it harder to introduce particular classes of vulnerability, such as cross-site scripting errors.

But there is, she suggests, too much security theatre. Companies still address faults because they are visible, but hold off fixing things that the public can’t see, or use non-disclosure agreements to buy silence from researchers to keep vulnerabilities from the public.

Moussouris believes that AI will ultimately take over from human bug researchers, but says the loss of expertise will damage security.

The world is on the verge of another industrial revolution, but it will be bigger and faster than the last industrial revolution. In the 19th century, people left agriculture to work long hours in factories, often in dangerous conditions for poor wages.

As AI takes over more tasks currently carried out by people, unemployment will rise, incomes will fall and economies risk stagnation, Moussouris predicts.

The only answer, she believes, is for governments to tax AI companies and use the proceeds to provide the population with a universal basic income (UBI). “I think it has to, or literally there will be no way for capitalism to survive,” she says. “The good news is that human engineering ingenuity is still intact for now. I still believe in our ability to hack our way out of this problem.”

Growing tensions between governments and bug bounty hunters

The work of bug bounty hunters has also been impacted by moves to require software technology companies to report vulnerabilities to governments before they fix them.

It began with China in 2021, which required tech companies to disclose new vulnerabilities within 48 hours of discovery.

“It was very clear that they were going to evaluate whether or not they were going to use vulnerabilities for offensive purposes,” says Moussouris.

In 2020, the European Union (EU) introduced the Cyber Resilience Act (CRA), which introduced similar disclosure obligations, ostensibly to allow European government to prepare their cyber defences.

Moussouris is a co-author of the ISO standard on vulnerability disclosure. One of its principles is to limit the knowledge of security bugs to the smallest number of people before they are fixed.

The EU argues that its approach will be safe because it is not asking for a deep technical explanation of the vulnerabilities, nor is it asking for proof-of-concept code to show how vulnerabilities can be exploited.

But that misses the point, says Moussouris. Widening the pool of people with access to information about vulnerabilities will make leaks more likely and raises the risk that criminal hackers or hostile nation-states will exploit them for crime or espionage.

Risk from hostile nations

Moussouris does not doubt that hostile nations will exploit the weakest links in government bug notification schemes to learn new security exploits. If they are already using those vulnerabilities for offensive hacking, they will be able to cover their tracks.

“I anticipate there will be an upheaval in the threat intelligence landscape because our adversaries absolutely know this law is going to take effect. They are certainly positioning themselves to learn about these things through the leakiest party that gets notified,” she says.

“And they will either start targeting that particular software, if they weren’t already, or start pulling back their operations or hiding their tracks if they were the ones using it. It’s counterproductive,” she adds.

Moussouris is concerned that the US will likely follow the EU by introducing its own bug reporting scheme. “I am just holding my breath, anticipating that the US is going to follow, but I have been warning them against it.”

The UK’s equities programme

In the UK, GCHQ regulates government use of security vulnerabilities for spying through a process known as the equities scheme.

That involves security experts weighing up whether the UK would place its own critical systems at risk if it failed to notify software suppliers of potential exploits against the potential value of the exploit for gathering intelligence.

The process has a veneer of rationality, but it falls down because, in practice, government experts can have no idea how widespread vulnerabilities are in the critical national infrastructure. Even large suppliers like Microsoft have trouble tracking where their own products are used.

“When I was working at Microsoft, it was very clear that while Microsoft had a lot of visibility into what was deployed in the world, there were tonnes of things out there that they wouldn’t know about until they were exploited,” she says.

“The fact that Microsoft, with all its telemetry ability to know where its customers are, struggled means there is absolutely no way to gauge in a reliable way how vulnerable we are,” she adds.

Kate Moussouris spoke to Computer Weekly at the SANS CyberThreat Summit.

Tech

Onnit’s Instant Melatonin Spray Is the Easiest Part of My Nightly Routine

I’ve always approached taking melatonin supplements with skepticism. They seem to help every once in a while, but your brain is already making melatonin. Beyond that, I am not a fan of the sickly-sweet tablets, gummies, and other forms of melatonin I’ve come across. No one wants a bad taste in their mouth when they’re supposed to be drifting off to sleep.

This is where Onnit’s Instant Melatonin Spray comes in. Fellow WIRED reviewer Molly Higgins first gave it a go, and reported back favorably. This spray comes in two flavors, lavender and mint, and is sweetened with stevia. While I wouldn’t consider it a gourmet taste, I appreciate that it leans more into herbal components known for sleep and relaxation.

Keep in mind that melatonin is meant to be a sleep aid, not a cure-all. That being said, one serving of this spray has 3 milligrams of melatonin, which takes about six pumps to dispense. While 3 milligrams may not seem like a lot to really kickstart your circadian rhythm, it’s actually the ideal dosage to get your brain’s wind-down process kicked off. Some people can do more (but don’t go over 10 milligrams!), some less, but based on what experts have relayed to me, this is the preferable amount.

A couple of reminders for any supplement: consult your doctor if and when you want to incorporate anything, melatonin included, into your nighttime regimen. Your healthcare provider can help confirm that you’re not on any medications where adding a sleep aid or supplement wouldn’t feel as effective. Onnit’s Instant Melatonin Spray is International Genetically Modified Organism Evaluation and Notification certified (IGEN) to verify that it uses truly non-GMO ingredients.

Apart from that, there may be some trial and error on the ideal amount for you, and how much time it takes to kick in. Some may feel the melatonin sooner than others. For my colleague Molly, it took about an hour. Melatonin can’t do all the heavy lifting, so make sure you’re ready to go to bed when you take it, and that your sleep space is set up for sleep success, down to your mattress, sheets, and pillows.

Tech

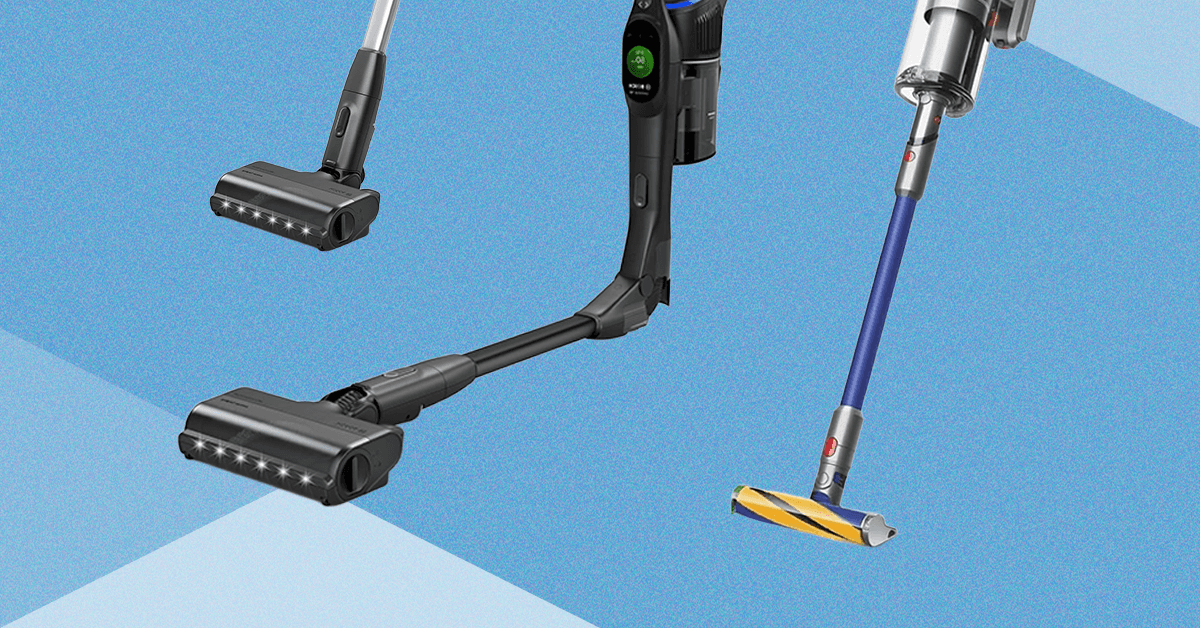

I Tested Bosch’s New Vacuum Against Shark and Dyson. It Didn’t Beat Them

There’s a lever on the back for this compression mechanism that you manually press down and a separate button to open the dustbin at the bottom. You can use the compression lever when it’s both closed and open. It did help compress the hair and dust while I was vacuuming, helping me see if I had really filled the bin, though at a certain point it doesn’t compress much more. It was helpful to push debris out if needed too, versus the times I’ve had to stick my hand in both the Dyson and Shark to get the stuck hair and dust out. Dyson has this same feature on the Piston Animal V16, which is due out this year, so I’ll be curious to see which mechanism is better engineered.

Bendable Winner: Shark

Photograph: Nena Farrell

If you’re looking for a vacuum that can bend to reach under furniture, I prefer the Shark to the Bosch. Both have a similar mechanism and feel, but the Bosch tended to push debris around when I was using it with an active bend, while the Shark managed to vacuum up debris I couldn’t get with the Bosch without lifting it and placing it on top of that particular debris (in this case, rogue cat kibble).

Accessory Winner: Dyson

Dyson pulls ahead because the Dyson Gen5 Detect comes with three attachments and two heads. You’ll get a Motorbar head, a Fluffy Optic head, a hair tool, a combination tool, and a dusting and crevice tool that’s actually built into the stick tube. I love that it’s built into the vacuum so that it’s one less separate attachment to carry around, and it makes me more likely to use it.

But Bosch does well in this area, too. You’ll get an upholstery nozzle, a furniture brush, and a crevice nozzle. It’s one more attachment than you’ll get with Shark, and Bosch also includes a wall mount that you can wire the charging cord into for storage and charging, and you can mount two attachments on it. But I will say, I like that Shark includes a simple tote bag to store the attachments in. The rest of my attachments are in plastic bags for each vacuum, and keeping track of attachments is the most annoying part of a cordless vacuum.

Build Winner: Tie

Photograph: Nena Farrell

All three of these vacuums have a good build quality, but each one feels like it focuses on something different. Bosch feels the lightest of the three and stands up the easiest on its own, but all three do need something to lean against to stay upright. The Dyson is the worst at this; it also needs a ledge or table wedged under the canister, or it’ll roll forward and tip over. The Bosch has a sleek black look and a colorful LED screen that will show you a picture of carpet or hardwood depending on what mode it’s vacuuming in. The vacuum head itself feels like the lightest plastic of the bunch, though.

Tech

Right-Wing Gun Enthusiasts and Extremists Are Working Overtime to Justify Alex Pretti’s Killing

Brandon Herrera, a prominent gun influencer with over 4 million followers on YouTube, said in a video posted this week that while it was unfortunate that Pretti died, ultimately the fault was his own.

“Pretti didn’t deserve to die, but it also wasn’t just a baseless execution,” Herrera said, adding without evidence that Pretti’s purpose was to disrupt ICE operations. “If you’re interfering with arrests and things like that, that’s a crime. If you get in the fucking officer’s way, that will probably be escalated to physical force, whether it’s arresting you or just getting you the fuck out of the way, which then can lead to a tussle, which, if you’re armed, can lead to a fatal shooting.” He described the situation as “lawful but awful.”

Herrera was joined in the video by former police officer and fellow gun influencer Cody Garrett, known online as Donut Operator.

Both men took the opportunity to deride immigrants, with Herrera saying “every news outlet is going to jump onto this because it’s current thing and they’re going to ignore the 12 drunk drivers who killed you know, American citizens yesterday that were all illegals or H-1Bs or whatever.”

Herrera also referenced his “friend” Kyle Rittenhouse, who has become central to much of the debate about the shooting.

On August 25, 2020, Rittenhouse, who was 17 at the time, traveled from his home in Illinois to a protest in Kenosha, Wisconsin, brandishing an AR-15-style rifle, claiming he was there to protect local businesses. He killed two people and shot another in the arm that night.

Critics of ICE’s actions in Minneapolis quickly highlighted what they saw as the hypocrisy of the right’s defense of Rittenhouse and attacks on Pretti.

“Kyle Rittenhouse was a conservative hero for walking into a protest actually brandishing a weapon, but this guy who had a legal permit to carry and already had had his gun removed is to some people an instigator, when he was actually going to help a woman,” Jessica Tarlov, a Democratic strategist, said on Fox News this week.

Rittenhouse also waded into the debate, writing on X: “The correct way to approach law enforcement when armed,” above a picture of himself with his hands up in front of police after he killed two people. He added in another post that “ICE messed up.”

The claim that Pretti was to blame was repeated in private Facebook groups run by armed militias, according to data shared with WIRED by the Tech Transparency Project, as well as on extremist Telegram channels.

“I’m sorry for him and his family,” one member of a Facebook group called American Patriots wrote. “My question though, why did he go to these riots armed with a gun and extra magazines if he wasn’t planning on using them?”

Some extremist groups, such as the far-right Boogaloo movement, have been highly critical of the administration’s comments on being armed at a protest.

“To the ‘dont bring a gun to a protest’ crowd, fuck you,” one member of a private Boogaloo group wrote on Facebook this week. “To the fucking turn coats thinking disarming is the answer and dont think it would happen to you as well, fuck you. To the federal government who I’ve watched murder citizens just for saying no to them, fuck you. Shall not be infringed.”

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoSuccess Story: This IITian Failed 17 Times Before Building A ₹40,000 Crore Giant

-

Fashion1 week ago

Fashion1 week agoSouth Korea tilts sourcing towards China as apparel imports shift

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoPSL 11: Local players’ category renewals unveiled ahead of auction

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoWanted Olympian-turned-fugitive Ryan Wedding in custody, sources say

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoStrap One of Our Favorite Action Cameras to Your Helmet or a Floaty

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoThree dead after suicide blast targets peace committee leader’s home in DI Khan

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoThis Mega Snowstorm Will Be a Test for the US Supply Chain

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoStorylines shaping the 2025-26 men’s college basketball season