Entertainment

Keira Knightley reveals reason for feeling ‘fortunate’

Keira Knightley feels “fortunate” to have survived her early experiences of fame.

The 40-year-old actress has enjoyed a very successful career in the film industry, having starred in Bend It Like Beckham back in 2002 – but Keira acknowledges that her life and her career could’ve easily gone in another direction.

Speaking to The Independent, Keira explained: “The adult me is very aware that people can go through very difficult periods in their life, and they do not come out of it with a very successful career and a very healthy bank balance. I feel incredibly fortunate.”

The Pride and Prejudice star also acknowledged that she’s now achieved a level of respect from the public that didn’t exist during her teenage years.

“I think being a 40-year-old woman, people have a different response to you than when you’re 18. That’s just the way the world is,” she said.

Keira added, “When you’re 18, you haven’t got much work, you’re all image. When you have a career that’s 25 years long, and you’ve got enough stuff to be like, ‘Well, that’s a body of work; some worked, some didn’t’ – people can look, and go, ‘That’s a career.’”

Meanwhile, the Black Doves talent previously claimed that there’s “an inherent rage to actors.”

Keira Knightley told the Guardian newspaper: “I think there’s an inherent rage to actors. I see that quite a lot. Masked brilliantly but easy to access.”

“Not that people behave badly, because generally they don’t. But there’s a well of anger that opens very quickly,” she concluded.

Entertainment

Over 73,000 passengers offloaded in 2025: interior ministry

- 35,270 passengers were offloaded in 2023: interior ministry.

- Number of those offloaded increased to 39,214 in 2024, it adds.

- 45,356 passengers offloaded in 2025 on technical grounds.

In the wake of tightened screening measures at airports and growing reports of passengers being offloaded, the Ministry of Interior has revealed that more than 73,000 passengers were offloaded during 2025.

“A total of 35,270 passengers were offloaded in 2023, 39,214 in 2024 and 73,358 in 2025,” read the Ministry of Interior’s reply to a question in the Senate, adding that 147,842 passengers were offloaded during the three-year period.

The ministry’s submission comes against the backdrop of thousands of Pakistanis being deported from various countries for begging, while tens of thousands were also offloaded at airports over suspected illegal travel attempts, a National Assembly committee was informed in December 2025.

Last month, Interior Minister Mohsin Naqvi directed the relevant authorities to enforce strict screening of passengers’ travel documents at all airports across the country to curb illegal immigration.

Directing the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) to continue strict and impartial action against the mafia involved in illegal immigration, he ordered the agency to ensure the effective implementation of immigration laws and strengthen airport immigration systems.

He also called for rigorous scrutiny of travellers’ documents at all airports to prevent illegal activities.

Meanwhile, explaining the reasons for passengers being offloaded, the interior ministry informed the Senate that only those passengers are offloaded whose behaviour indicates possible illegal intentions.

Out of the total 73,358 passengers offloaded in 2025, 45,356 were offloaded for technical reasons, including flight cancellations, passengers’ refusal to travel, technical faults in aircraft, bad weather, flight delays and offloading by airlines.

Providing data on illegal immigration attempts, the ministry said that 861 suspects carrying fake documents were identified at airports over the past three years.

It said that 303 suspects were deported on fake documents, 417 cases were registered, 557 people were arrested and 206 were convicted.

The ministry further stated that 153 additional cases were registered in connection with fake documents and deportations, 181 suspects were arrested and 93 were convicted.

It also noted that 23 departmental inquiries are under way against FIA employees over fake document cases, of which 17 have been concluded.

Beggars issue

The ministry also shared details of beggars who were offloaded and deported over the past two years.

It said that 507 beggars were offloaded in 2024 and 90 in 2025, while 49 inquiries and 32 first information reports (FIRs) were registered in connection with beggars offloaded in 2024.

Of those offloaded in 2024, 59 beggars and 17 agents were arrested and 19 were convicted.

Meanwhile, in 2025, 43 inquiries were initiated into beggars who were offloaded, 37 FIRs were registered and 36 beggars were arrested, while one was convicted.

The ministry further said that 4,850 beggars were deported in 2024, whereas the number declined to 1,187 in 2025.

It added that 105 inquiries and 48 FIRs were registered against beggars deported in 2024.

During the same year, 91 deported beggars and two agents were arrested, while 12 were convicted.

In 2025, the ministry said, 354 inquiries were initiated and 201 FIRs were registered, leading to the arrest of 589 beggars and one agent, of whom 27 were convicted.

Entertainment

Princess Kate sends ultimatum to Harry as royals land in grave crisis

Kate Middleton sped up her efforts to bring back Prince Harry to the royal fold, especially during hard times for the royal family.

The Princess of Wales is reportedly urging her brother-in-law to share his plans related to Princess Diana’s death anniversary, so it won’t spoil the Waleses plans.

As Harry is in the news related to a possible reunion with his family, Catherine does not want his actions to shatter reconciliation dreams, Heat World reported.

The source shared, “Royal aides have been working behind the scenes to ensure that Diana’s anniversary is marked in a way that William is comfortable with.”

However, the Sussexes are “said to be organising their own thing, despite requests to coordinate activities.”

Princess Kate seemingly is not in favour of any “clash” between the two brothers, who are already on the verge of lifelong estrangement.

An insider claimed that the future Queen warned Harry that if he wouldn’t share his plans for the sombre event, it “could be the final nail in the coffin for Kate.”

“She’s always tried to see both sides in the hope that Harry would come back to his family. But this situation risks crossing a line,” added the source.

The mother-of-three is no longer in favour of defying her husband William, as the upcoming occasion also holds a special place in his heart.

“She will always stand by her husband. If siding with William means going against Harry, so be it,” the report shared.

Notably, Kate Middleton’s ultimatum to Harry came at a time when the royal family once again made it to the negative limelight following Andrew and Fergie’s vulgar exchange with Epstein.

Entertainment

Royal Princess photo emerges in Epstein files weeks after Palace notice

Fears sweep royal families across Europe as shocking revelations have come to light in the latest tranche of Epstein files released by the Department of Justice in US.

King Charles had ousted his shamed brother Andrew from the royal fold, stripping off the shamed royal of his honours and titles including Prince-style, over his ties to convicted paedophile Jeffrey Epstein. After the King’s landmark move, a beloved royal’s name emerged in the documents.

The Swedish Royal Court had to release a statement which confirmed that Princess Sofia, wife of Prince Carl Philip, had met Epstein but asserted that Sofia did not have any contact with the financier since 2005.

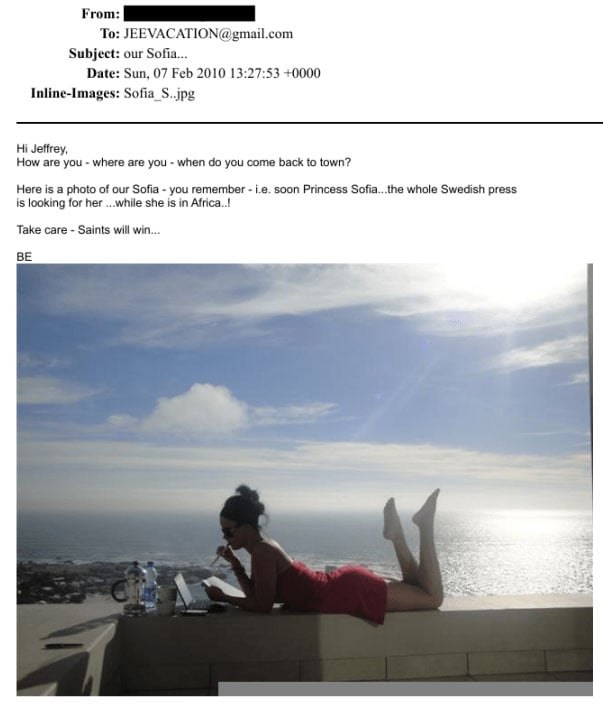

Although, a new email from 2010 reveals that Epstein was receiving updates on the Sofia, as she was getting ready to marry the Prince. Epstein had been interested in inviting Sofia to his private island in the Caribbean.

Sofia’s connection came from her mentor, financier Barbro Ehnbom, who had ties to Epstein. He had introduced her to Epstein as an “aspiring” actress.

In the email sent by Barbro, as it was signed off as ‘BE’, he sent a photo of “our Sofia” who had been enjoying her time in Africa.

Epstein replied by asking whether she wanted to come to the Caribbean and offering to send a ticket.

The exchange was from the time when Sofia had started dating the second son of King Carl XVI Gustaf. She went on to marry Prince Carl Philip in 2015, and welcomed four children together.

There has been no new statement from the Royal Courts so far.

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoPSL 11: Local players’ category renewals unveiled ahead of auction

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoCollege football’s top 100 games of the 2025 season

-

Entertainment7 days ago

Entertainment7 days agoClaire Danes reveals how she reacted to pregnancy at 44

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoBanking services disrupted as bank employees go on nationwide strike demanding five-day work week

-

Politics7 days ago

Politics7 days agoTrump vows to ‘de-escalate’ after Minneapolis shootings

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoBrighten Your Darkest Time (of Year) With This Smart Home Upgrade

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoTammy Abraham joins Aston Villa 1 day after Besiktas transfer

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoGM expects to top Ford in U.S. vehicle production as it faces up to $4 billion in tariff costs