Tech

Lumbar Support Can Make a Huge Difference in Your Office Chair

I also spoke to John Gallucci, a licensed physical therapist and athletic trainer who specializes in treating symptoms from poor office posture, and he confirmed much of what Egbert said. Closed case, right? Well, it’s certainly not just marketing speak so that office chair manufacturers can charge you extra. But there are some important factors to consider.

Not All Lumbar Support Is Equal

Gallucci was quick to point out the benefits of lumbar support, but he also issued some warnings about how to proceed. Turns out, not all lumbar support is equal. “The most important thing to look for in a chair is ergonomic adjustability,” he says, referencing the need for adjustable lumbar support. “A good chair should support your posture for long periods without causing discomfort or fatigue. That means it should allow you to adjust the seat height, seat pan depth, armrests, lumbar support, and backrest tilt.”

Chairs with fixed lumbar support mean it isn’t adjustable to your body. Lumbar support and adjustments come in different forms these days. For example, some chairs have lumbar height adjustment but not depth, also known as “two-way” adjustment. Some use a dial for adjustment, and others use a ratchet or lever system. Other chairs let you adjust the entire backrest to find the right position, and some cheaper chairs resort to just a simple pad that can be manually moved. These can, in theory, all be good solutions, so long as you’re able to find the right position.

“That curve has to be adjustable as to where it is,” Egbert says. “My butt might be lower than your butt, and you want it to match where that curve in your lower back is. You want to be able to slide it up and down.”

A good example of an ergonomic chair with “two-way” lumbar adjustment is the Branch Ergonomic Chair Pro. We’ve tested dozens of chairs, and this excellent lumbar support is one of the reasons WIRED’s office chair reviewer, Julian Chokkattu, found it so comfortable. It also doesn’t cost over a thousand dollars like so many high-end office chairs.

If you aren’t ready to shell out $500 on an ergonomic chair, that doesn’t mean you have to be doomed to lower back pain. Some DIY solutions can even be better than a chair with inadequate lumbar adjustment. We’ve even tested some add-on lumbar cushions that we like, such as this LoveHome model you can find on Amazon.

When it comes down to it, though, lumbar support isn’t the first thing to tackle when setting up your workspace. If you’re sitting at an old desk working from only a laptop, lumbar support is never going to solve your posture issues. Fix that first, with either a laptop stand or a height-adjustable monitor.

After that, yes, lumbar support is a good thing. It needs to be adjustable and well-implemented, but it’s something you’ll want to make sure is available on your next office chair. If you’re sitting for eight hours a day, your back deserves it.

Tech

Onnit’s Instant Melatonin Spray Is the Easiest Part of My Nightly Routine

I’ve always approached taking melatonin supplements with skepticism. They seem to help every once in a while, but your brain is already making melatonin. Beyond that, I am not a fan of the sickly-sweet tablets, gummies, and other forms of melatonin I’ve come across. No one wants a bad taste in their mouth when they’re supposed to be drifting off to sleep.

This is where Onnit’s Instant Melatonin Spray comes in. Fellow WIRED reviewer Molly Higgins first gave it a go, and reported back favorably. This spray comes in two flavors, lavender and mint, and is sweetened with stevia. While I wouldn’t consider it a gourmet taste, I appreciate that it leans more into herbal components known for sleep and relaxation.

Keep in mind that melatonin is meant to be a sleep aid, not a cure-all. That being said, one serving of this spray has 3 milligrams of melatonin, which takes about six pumps to dispense. While 3 milligrams may not seem like a lot to really kickstart your circadian rhythm, it’s actually the ideal dosage to get your brain’s wind-down process kicked off. Some people can do more (but don’t go over 10 milligrams!), some less, but based on what experts have relayed to me, this is the preferable amount.

A couple of reminders for any supplement: consult your doctor if and when you want to incorporate anything, melatonin included, into your nighttime regimen. Your healthcare provider can help confirm that you’re not on any medications where adding a sleep aid or supplement wouldn’t feel as effective. Onnit’s Instant Melatonin Spray is International Genetically Modified Organism Evaluation and Notification certified (IGEN) to verify that it uses truly non-GMO ingredients.

Apart from that, there may be some trial and error on the ideal amount for you, and how much time it takes to kick in. Some may feel the melatonin sooner than others. For my colleague Molly, it took about an hour. Melatonin can’t do all the heavy lifting, so make sure you’re ready to go to bed when you take it, and that your sleep space is set up for sleep success, down to your mattress, sheets, and pillows.

Tech

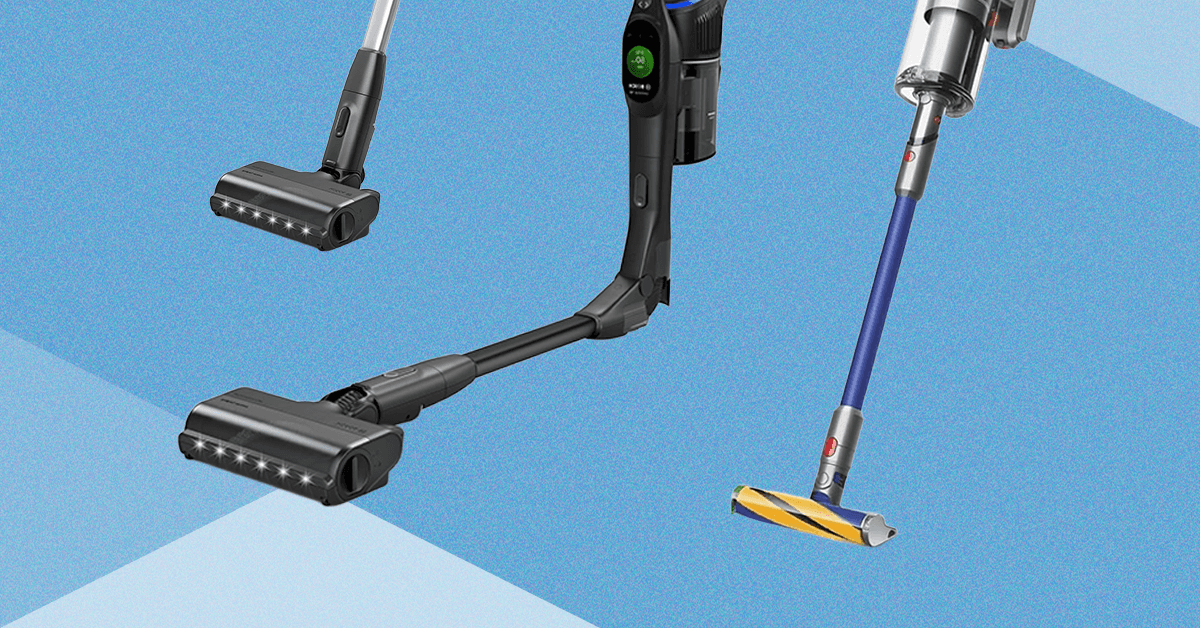

I Tested Bosch’s New Vacuum Against Shark and Dyson. It Didn’t Beat Them

There’s a lever on the back for this compression mechanism that you manually press down and a separate button to open the dustbin at the bottom. You can use the compression lever when it’s both closed and open. It did help compress the hair and dust while I was vacuuming, helping me see if I had really filled the bin, though at a certain point it doesn’t compress much more. It was helpful to push debris out if needed too, versus the times I’ve had to stick my hand in both the Dyson and Shark to get the stuck hair and dust out. Dyson has this same feature on the Piston Animal V16, which is due out this year, so I’ll be curious to see which mechanism is better engineered.

Bendable Winner: Shark

Photograph: Nena Farrell

If you’re looking for a vacuum that can bend to reach under furniture, I prefer the Shark to the Bosch. Both have a similar mechanism and feel, but the Bosch tended to push debris around when I was using it with an active bend, while the Shark managed to vacuum up debris I couldn’t get with the Bosch without lifting it and placing it on top of that particular debris (in this case, rogue cat kibble).

Accessory Winner: Dyson

Dyson pulls ahead because the Dyson Gen5 Detect comes with three attachments and two heads. You’ll get a Motorbar head, a Fluffy Optic head, a hair tool, a combination tool, and a dusting and crevice tool that’s actually built into the stick tube. I love that it’s built into the vacuum so that it’s one less separate attachment to carry around, and it makes me more likely to use it.

But Bosch does well in this area, too. You’ll get an upholstery nozzle, a furniture brush, and a crevice nozzle. It’s one more attachment than you’ll get with Shark, and Bosch also includes a wall mount that you can wire the charging cord into for storage and charging, and you can mount two attachments on it. But I will say, I like that Shark includes a simple tote bag to store the attachments in. The rest of my attachments are in plastic bags for each vacuum, and keeping track of attachments is the most annoying part of a cordless vacuum.

Build Winner: Tie

Photograph: Nena Farrell

All three of these vacuums have a good build quality, but each one feels like it focuses on something different. Bosch feels the lightest of the three and stands up the easiest on its own, but all three do need something to lean against to stay upright. The Dyson is the worst at this; it also needs a ledge or table wedged under the canister, or it’ll roll forward and tip over. The Bosch has a sleek black look and a colorful LED screen that will show you a picture of carpet or hardwood depending on what mode it’s vacuuming in. The vacuum head itself feels like the lightest plastic of the bunch, though.

Tech

Right-Wing Gun Enthusiasts and Extremists Are Working Overtime to Justify Alex Pretti’s Killing

Brandon Herrera, a prominent gun influencer with over 4 million followers on YouTube, said in a video posted this week that while it was unfortunate that Pretti died, ultimately the fault was his own.

“Pretti didn’t deserve to die, but it also wasn’t just a baseless execution,” Herrera said, adding without evidence that Pretti’s purpose was to disrupt ICE operations. “If you’re interfering with arrests and things like that, that’s a crime. If you get in the fucking officer’s way, that will probably be escalated to physical force, whether it’s arresting you or just getting you the fuck out of the way, which then can lead to a tussle, which, if you’re armed, can lead to a fatal shooting.” He described the situation as “lawful but awful.”

Herrera was joined in the video by former police officer and fellow gun influencer Cody Garrett, known online as Donut Operator.

Both men took the opportunity to deride immigrants, with Herrera saying “every news outlet is going to jump onto this because it’s current thing and they’re going to ignore the 12 drunk drivers who killed you know, American citizens yesterday that were all illegals or H-1Bs or whatever.”

Herrera also referenced his “friend” Kyle Rittenhouse, who has become central to much of the debate about the shooting.

On August 25, 2020, Rittenhouse, who was 17 at the time, traveled from his home in Illinois to a protest in Kenosha, Wisconsin, brandishing an AR-15-style rifle, claiming he was there to protect local businesses. He killed two people and shot another in the arm that night.

Critics of ICE’s actions in Minneapolis quickly highlighted what they saw as the hypocrisy of the right’s defense of Rittenhouse and attacks on Pretti.

“Kyle Rittenhouse was a conservative hero for walking into a protest actually brandishing a weapon, but this guy who had a legal permit to carry and already had had his gun removed is to some people an instigator, when he was actually going to help a woman,” Jessica Tarlov, a Democratic strategist, said on Fox News this week.

Rittenhouse also waded into the debate, writing on X: “The correct way to approach law enforcement when armed,” above a picture of himself with his hands up in front of police after he killed two people. He added in another post that “ICE messed up.”

The claim that Pretti was to blame was repeated in private Facebook groups run by armed militias, according to data shared with WIRED by the Tech Transparency Project, as well as on extremist Telegram channels.

“I’m sorry for him and his family,” one member of a Facebook group called American Patriots wrote. “My question though, why did he go to these riots armed with a gun and extra magazines if he wasn’t planning on using them?”

Some extremist groups, such as the far-right Boogaloo movement, have been highly critical of the administration’s comments on being armed at a protest.

“To the ‘dont bring a gun to a protest’ crowd, fuck you,” one member of a private Boogaloo group wrote on Facebook this week. “To the fucking turn coats thinking disarming is the answer and dont think it would happen to you as well, fuck you. To the federal government who I’ve watched murder citizens just for saying no to them, fuck you. Shall not be infringed.”

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoSuccess Story: This IITian Failed 17 Times Before Building A ₹40,000 Crore Giant

-

Fashion1 week ago

Fashion1 week agoSouth Korea tilts sourcing towards China as apparel imports shift

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoPSL 11: Local players’ category renewals unveiled ahead of auction

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoWanted Olympian-turned-fugitive Ryan Wedding in custody, sources say

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoStrap One of Our Favorite Action Cameras to Your Helmet or a Floaty

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoThree dead after suicide blast targets peace committee leader’s home in DI Khan

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoThis Mega Snowstorm Will Be a Test for the US Supply Chain

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoStorylines shaping the 2025-26 men’s college basketball season