Tech

Security pros should prepare for tough questions on AI in 2026 | Computer Weekly

For the last couple of years, many organisations have comforted themselves with a single slide or paragraph that reads along the lines of “We use artificial intelligence [AI] responsibly.” That line might have been enough to get through informal supplier due diligence in 2023 but it will not survive the next serious round of tenders.

Enterprise buyers, particularly in government, defence and critical national infrastructure (CNI), are now using AI heavily themselves. They understand the risk language. They are making connections between AI, data protection, operational resilience and supply chain exposure. Their procurement teams will no longer ask whether you use AI. They will ask how you govern it.

The AI question is changing

In practical terms, the questions in requests for proposals (RFPs) and invitations to tender (ITTs) are already shifting.

Instead of the soft “Do you use AI in your services?”, you can expect wording more like:

“Please describe your controls for generative AI, including data sovereignty, human oversight, model accountability and compliance with relevant data protection, security and intellectual property obligations.”

Underneath that line sit a number of very specific concerns.

Where is client or citizen data going when you use tools such as ChatGPT, Claude or other hosted models?

Which jurisdictions does that data transit or reside in?

How is AI assisted output checked by humans before it influences a critical decision, a piece of advice, or a safety related activity?

Who owns and can reuse the prompts and outputs, and how is confidential or classified material protected in that process?

The generic boilerplate no longer answers any of those points. In fact, it advertises that there is no structured governance at all.

The uncomfortable reality in many service providers is that if you strip away the marketing language, most professional services organisations are using AI in a very familiar pattern.

Individual staff have adopted tools to speed up drafting, analysis or coding. Teams share tips informally. Some groups have written local guidance on what is acceptable. A few policies have been updated to mention AI.

What is often missing is evidence

Very few organisations can say with certainty which client engagements involved AI assistance, what categories of data were used in prompts, which models or providers were involved, where those providers processed and stored the information, and how review and approval of AI output was recorded.

From a governance, risk and compliance (GRC) perspective, that is a problem. It touches data protection, information security, records management, professional indemnity, and in some sectors safety and mission assurance. It also follows you into every future tender, because buyers are increasingly asking about past AI related incidents, near misses and lessons learned.

Why this matters so much in government, defence and CNI

In central and local government, policing and justice, AI is increasingly influencing decisions that affect citizens directly. That might be in triaging cases, prioritising inspections, supporting investigations or shaping policy analysis.

When AI is involved in those processes, public bodies must be able to show lawful basis, transparency, fairness and accountability. That means understanding where AI is used, how it is supervised, and how outputs are challenged or overridden. Suppliers into that space are expected to demonstrate the same discipline.

In the defence and wider national security supply chain, the stakes are even higher. AI is already appearing in logistics optimisation, predictive maintenance, intelligence fusion, training environments and decision support. Here the questions are not just about privacy or intellectual property. They are about reliability under stress, robustness against manipulation, and assurance that sensitive operational data is not leaking into systems outside sovereign or approved control.

CNI operators have a similar challenge. Many are exploring AI for anomaly detection in OT environments, demand forecasting, and automated response. A failure or misfire here can quickly turn into a service outage, safety incident or environmental impact. Regulators will expect operators and their suppliers to treat AI as an element of operational risk, not a novelty tool.

In all of these sectors, the organisations that cannot explain their AI governance will quietly fall down the scoring matrix.

Turning AI governance into a commercial advantage

The good news is that this picture can be turned around. AI governance, done properly, is not about slowing down or banning innovation. It is about putting enough structure around AI use that you can explain it, defend it and scale it.

A practical starting point is an AI procurement readiness assessment. At Advent IM, we describe this in very simple terms: can you answer the questions your next major client is going to ask?

That involves mapping where AI is used across your services, identifying which workflows touch client or citizen data, understanding which third party models or platforms are involved, and documenting how humans supervise, approve or override AI outputs. It also means looking at how AI fits into your existing incident response, data breach handling and risk registers.

From there, you can develop a short, evidence-based narrative that fits neatly into RFP and ITT responses, backed by policies, process descriptions and example logs. Instead of hand waving about responsible AI, you can present a clear story about how AI is governed as part of your wider security and GRC framework.

ISO 42001 as the backbone for AI governance

ISO IEC 42001, the new standard for AI management systems, gives this work structure. It provides a framework for managing AI across its lifecycle, from design and acquisition through to operation, monitoring and retirement.

For organisations that already operate an information security management system (ISMS), quality management system or privacy information management system, 42001 should not feel alien. It can be integrated with existing ISO 27001, 9001 and 27701 arrangements. Roles such as senior information risk owner (SIRO), information asset owner (IAO), data protection officer, heads of service and system owners simply gain clearer responsibilities for AI related activities.

Aligning with 42001 also signals to clients, regulators and insurers that AI is not being treated informally. It shows that there are defined roles, documented processes, risk assessments, monitoring and continual improvement around AI. Over time, that alignment can be taken further into formal certification for those organisations where it makes commercial sense.

Bringing people, process and assurance together

Policies and frameworks are only part of the picture. The real test is whether people across the organisation understand what is permitted, what is prohibited, and when they need to ask for help.

AI security and governance training is therefore critical. Staff need to understand how to handle prompts that contain personal or sensitive data, how to recognise when AI outputs might be biased or incomplete, and how to record their own oversight. Managers need to know how to approve use cases, sign off risk assessments and respond to incidents involving AI.

Bringing all of this together gives you something very simple but very powerful. When the next RFP or ITT lands with a page of questions about AI, you will not be scrambling for ad hoc answers. You will be able to describe an AI management system that is aligned to recognised standards, integrated with your existing security and GRC practices, and backed by training and evidence.

In a crowded services market, that may be the difference between being seen as an interesting supplier and being trusted with high value, sensitive work.

Tech

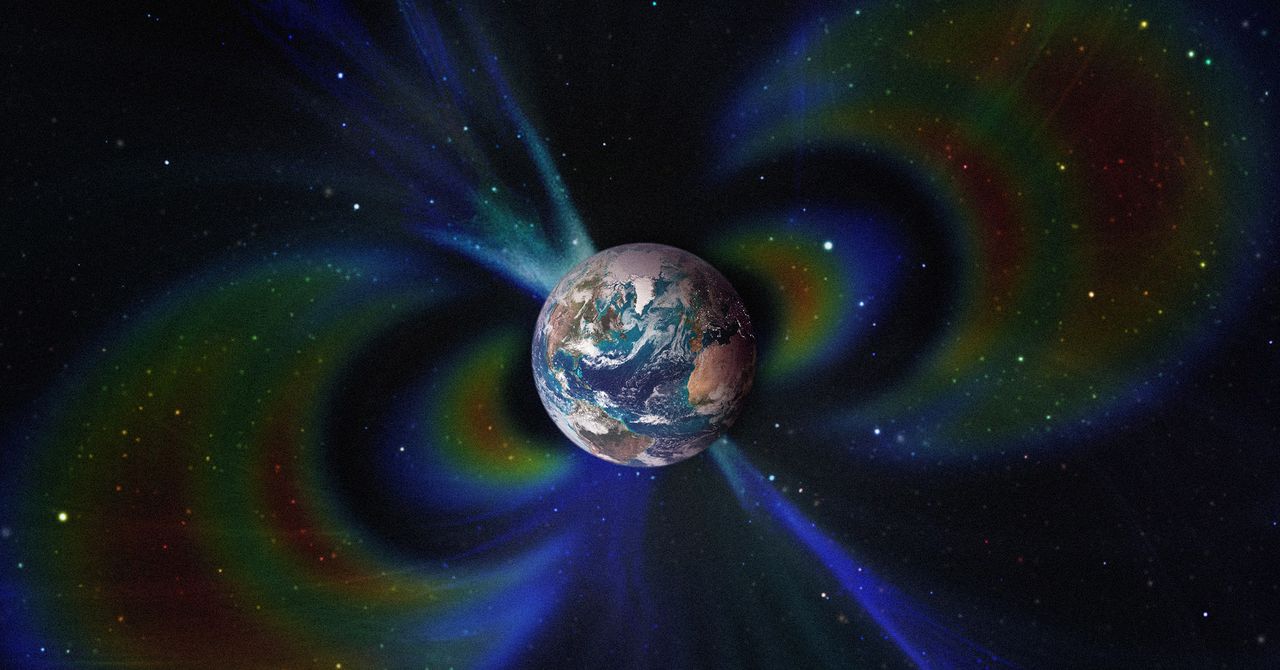

Two Titanic Structures Hidden Deep Within the Earth Have Altered the Magnetic Field for Millions of Years

A team of geologists has found for the first time evidence that two ancient, continent-sized, ultrahot structures hidden beneath the Earth have shaped the planet’s magnetic field for the past 265 million years.

These two masses, known as large low-shear-velocity provinces (LLSVPs), are part of the catalog of the planet’s most enormous and enigmatic objects. Current estimates calculate that each one is comparable in size to the African continent, although they remain buried at a depth of 2,900 kilometers.

Low-lying surface vertical velocity (LLVV) regions form irregular areas of the Earth’s mantle, not defined blocks of rock or metal as one might imagine. Within them, the mantle material is hotter, denser, and chemically different from the surrounding material. They are also notable because a “ring” of cooler material surrounds them, where seismic waves travel faster.

Geologists had suspected these anomalies existed since the late 1970s and were able to confirm them two decades later. After another 10 years of research, they now point to them directly as structures capable of modifying Earth’s magnetic field.

LLSVPs Alter the Behavior of the Nucleus

According to a study published this week in Nature Geoscience and led by researchers at the University of Liverpool, temperature differences between LLSVPs and the surrounding mantle material alter the way liquid iron flows in the core. This movement of iron is responsible for generating Earth’s magnetic field.

Taken together, the cold and ultrahot zones of the mantle accelerate or slow the flow of liquid iron depending on the region, creating an asymmetry. This inequality contributes to the magnetic field taking on the irregular shape we observe today.

The team analyzed the available mantle evidence and ran simulations on supercomputers. They compared how the magnetic field should look if the mantle were uniform versus how it behaves when it includes these heterogeneous regions with structures. They then contrasted both scenarios with real magnetic field data. Only the model that incorporated the LLSVPs reproduced the same irregularities, tilts, and patterns that are currently observed.

The geodynamo simulations also revealed that some parts of the magnetic field have remained relatively stable for hundreds of millions of years, while others have changed remarkably.

“These findings also have important implications for questions surrounding ancient continental configurations—such as the formation and breakup of Pangaea—and may help resolve long-standing uncertainties in ancient climate, paleobiology, and the formation of natural resources,” said Andy Biggin, first author of the study and professor of Geomagnetism at the University of Liverpool, in a press release.

“These areas have assumed that Earth’s magnetic field, when averaged over long periods, behaved as a perfect bar magnet aligned with the planet’s rotational axis. Our findings are that this may not quite be true,” he added.

This story originally appeared in WIRED en Español and has been translated from Spanish.

Tech

Loyalty Is Dead in Silicon Valley

Since the middle of last year, there have been at least three major AI “acqui-hires” in Silicon Valley. Meta invested more than $14 billion in Scale AI and brought on its CEO, Alexandr Wang; Google spent a cool $2.4 billion to license Windsurf’s technology and fold its cofounders and research teams into DeepMind; and Nvidia wagered $20 billion on Groq’s inference technology and hired its CEO and other staffers.

The frontier AI labs, meanwhile, have been playing a high stakes and seemingly never-ending game of talent musical chairs. The latest reshuffle began three weeks ago, when OpenAI announced it was rehiring several researchers who had departed less than two years earlier to join Mira Murati’s startup, Thinking Machines. At the same time, Anthropic, which was itself founded by former OpenAI staffers, has been poaching talent from the ChatGPT maker. OpenAI, in turn, just hired a former Anthropic safety researcher to be its “head of preparedness.”

The hiring churn happening in Silicon Valley represents the “great unbundling” of the tech startup, as Dave Munichiello, an investor at GV, put it. In earlier eras, tech founders and their first employees often stayed onboard until either the lights went out or there was a major liquidity event. But in today’s market, where generative AI startups are growing rapidly, equipped with plenty of capital, and prized especially for the strength of their research talent, “you invest in a startup knowing it could be broken up,” Munichiello told me.

Early founders and researchers at the buzziest AI startups are bouncing around to different companies for a range of reasons. A big incentive for many, of course, is money. Last year Meta was reportedly offering top AI researchers compensation packages in the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, offering them not just access to cutting-edge computing resources but also … generational wealth.

But it’s not all about getting rich. Broader cultural shifts that rocked the tech industry in recent years have made some workers worried about committing to one company or institution for too long, says Sayash Kapoor, a computer science researcher at Princeton University and a senior fellow at Mozilla. Employers used to safely assume that workers would stay at least until the four-year mark when their stock options were typically scheduled to vest. In the high-minded era of the 2000s and 2010s, plenty of early cofounders and employees also sincerely believed in the stated missions of their companies and wanted to be there to help achieve them.

Now, Kapoor says, “people understand the limitations of the institutions they’re working in, and founders are more pragmatic.” The founders of Windsurf, for example, may have calculated their impact could be larger at a place like Google that has lots of resources, Kapoor says. He adds that a similar shift is happening within academia. Over the past five years, Kapoor says, he’s seen more PhD researchers leave their computer-science doctoral programs to take jobs in industry. There are higher opportunity costs associated with staying in one place at a time when AI innovation is rapidly accelerating, he says.

Investors, wary of becoming collateral damage in the AI talent wars, are taking steps to protect themselves. Max Gazor, the founder of Striker Venture Partners, says his team is vetting founding teams “for chemistry and cohesion more than ever.” Gazor says it’s also increasingly common for deals to include “protective provisions that require board consent for material IP licensing or similar scenarios.”

Gazor notes that some of the biggest acqui-hire deals that have happened recently involved startups founded long before the current generative AI boom. Scale AI, for example, was founded in 2016, a time when the kind of deal Wang negotiated with Meta would have been unfathomable to many. Now, however, these potential outcomes might be considered in early term sheets and “constructively managed,” Gazor explains.

Tech

ICE and CBP’s Face-Recognition App Can’t Actually Verify Who People Are

The face-recognition app Mobile Fortify, now used by United States immigration agents in towns and cities across the US, is not designed to reliably identify people in the streets and was deployed without the scrutiny that has historically governed the rollout of technologies that impact people’s privacy, according to records reviewed by WIRED.

The Department of Homeland Security launched Mobile Fortify in the spring of 2025 to “determine or verify” the identities of individuals stopped or detained by DHS officers during federal operations, records show. DHS explicitly linked the rollout to an executive order, signed by President Donald Trump on his first day in office, which called for a “total and efficient” crackdown on undocumented immigrants through the use of expedited removals, expanded detention, and funding pressure on states, among other tactics.

Despite DHS repeatedly framing Mobile Fortify as a tool for identifying people through facial recognition, however, the app does not actually “verify” the identities of people stopped by federal immigration agents—a well-known limitation of the technology and a function of how Mobile Fortify is designed and used.

“Every manufacturer of this technology, every police department with a policy makes very clear that face recognition technology is not capable of providing a positive identification, that it makes mistakes, and that it’s only for generating leads,” says Nathan Wessler, deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project.

Records reviewed by WIRED also show that DHS’s hasty approval of Fortify last May was enabled by dismantling centralized privacy reviews and quietly removing department-wide limits on facial recognition—changes overseen by a former Heritage Foundation lawyer and Project 2025 contributor, who now serves in a senior DHS privacy role.

DHS—which has declined to detail the methods and tools that agents are using, despite repeated calls from oversight officials and nonprofit privacy watchdogs—has used Mobile Fortify to scan the faces not only of “targeted individuals,” but also people later confirmed to be US citizens and others who were observing or protesting enforcement activity.

Reporting has documented federal agents telling citizens they were being recorded with facial recognition and that their faces would be added to a database without consent. Other accounts describe agents treating accent, perceived ethnicity, or skin color as a basis to escalate encounters—then using face scanning as the next step once a stop is underway. Together, the cases illustrate a broader shift in DHS enforcement toward low-level street encounters followed by biometric capture like face scans, with limited transparency around the tool’s operation and use.

Fortify’s technology mobilizes facial capture hundreds of miles from the US border, allowing DHS to generate nonconsensual face prints of people who, “it is conceivable,” DHS’s Privacy Office says, are “US citizens or lawful permanent residents.” As with the circumstances surrounding its deployment to agents with Customs and Border Protection and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Fortify’s functionality is visible mainly today through court filings and sworn agent testimony.

In a federal lawsuit this month, attorneys for the State of Illinois and the City of Chicago said the app had been used “in the field over 100,000 times” since launch.

In Oregon testimony last year, an agent said two photos of a woman in custody taken with his face-recognition app produced different identities. The woman was handcuffed and looking downward, the agent said, prompting him to physically reposition her to obtain the first image. The movement, he testified, caused her to yelp in pain. The app returned a name and photo of a woman named Maria; a match that the agent rated “a maybe.”

Agents called out the name, “Maria, Maria,” to gauge her reaction. When she failed to respond, they took another photo. The agent testified the second result was “possible,” but added, “I don’t know.” Asked what supported probable cause, the agent cited the woman speaking Spanish, her presence with others who appeared to be noncitizens, and a “possible match” via facial recognition. The agent testified that the app did not indicate how confident the system was in a match. “It’s just an image, your honor. You have to look at the eyes and the nose and the mouth and the lips.”

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoPSX witnesses 6,000-point on Middle East tensions | The Express Tribune

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoThe Surface Laptop Is $400 Off

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoHere’s the Company That Sold DHS ICE’s Notorious Face Recognition App

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoBudget 2026: Defence, critical minerals and infra may get major boost

-

Tech4 days ago

Tech4 days agoHow to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics

-

Tech6 days ago

Tech6 days agoRight-Wing Gun Enthusiasts and Extremists Are Working Overtime to Justify Alex Pretti’s Killing

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoLabubu to open seven UK shops, after PM’s China visit

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoDarian Mensah, Duke settle; QB commits to Miami