Tech

The importance of upgrading to the latest Windows operating system | Computer Weekly

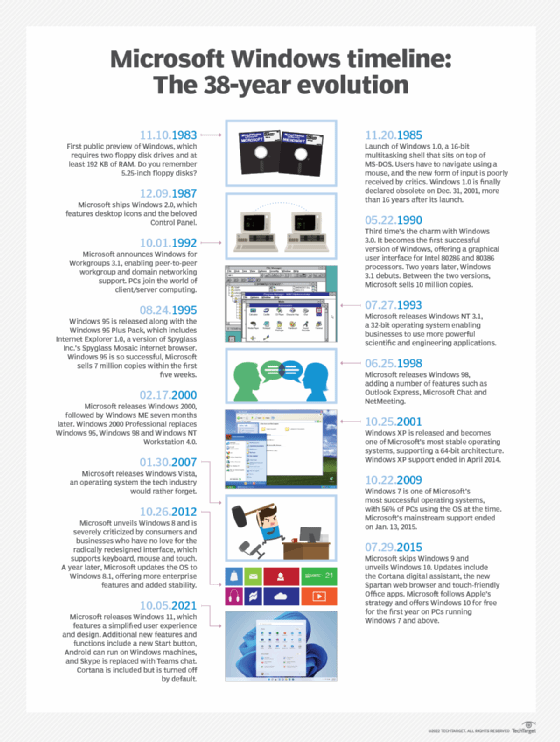

Windows 10 was launched in July 2015. It was supposed to be the last major operating system (OS) upgrade, but Microsoft released Windows 11 in October 2021, and now Windows 10 has reached end of life, which means it will no longer be updated.

Consumers who register for extended support and back up their PCs in the Microsoft cloud will be able to get free security updates until October 2026. Corporate PCs and devices connected to Active Directory will only receive Windows 10 security updates if they are covered by an Extended Security Updates (ESU) subscription.

In July, the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) warned that the security risks of not upgrading are significant. As the NCSC notes in a blog post on its website, in addition to the difficulties associated with being out of support, an out-of-date operating system is a prime target for cyber criminals.

“We saw this when a vulnerability in Internet Explorer 6-11 was exploited after Windows XP support ended on 8 April 2014, and before it was patched on 1 May 2014. And again in 2017, a vulnerability in unpatched versions of XP was exploited extensively by the WannaCry ransomware – an attack which resulted in huge costs and damage globally,” says the NCSC in the post.

Analyst Forrester’s Say goodbye to Windows 10 to reduce your cyber risk report points out that Windows 11 now has significant security features that are not available in Windows 10. These include administrator protection that Forrester says helps enable least privileged access. There is a feature called Smart App Control, which is used to validate the applications before they are run. In the report, Forrester notes that the latest version of Credential Guard extends account protection to machine account passwords, which is a new feature in Windows 11.

“Much has been made about Microsoft’s plans to better control the security of the kernel after CrowdStrike’s 2024 issue. Their goal isn’t to completely lock out vendors, but to ensure incidents like this don’t reoccur; if features and functions can be moved out of the kernel and into the user space, they should be,” write Forrester analysts Paddy Harrington, Merritt Maxim, Sophia Barrett and Christine Turley in the report.

But the improvements in Windows security also make it more difficult to move older hardware onto Windows 11. One of the difficulties holding organisations back is the hardware requirements of Windows 11, which introduced a need for PCs to have the Trusted Platform Module (TPM 2.0), UEFI and support for Secure Boot. “If your devices lack even one of these features, you’ll be unable to upgrade easily,” says the NCSC.

Following an analysis of its customers’ PCs, Nexthink estimates there has been a 33% decrease in Windows 10 devices between 19 May and 1 August. Assuming a further 33% reduction by 14 October – the date on which support officially ends – this leaves around 121 million Windows 10 PCs still running the operating system at the end of support deadline.

Discussing the challenge of migration, Tim Flower, DEX strategist at Nexthink, says: “Windows 11 brings powerful new capabilities, but only if devices and employees are ready to take advantage of them.”

Why Windows 10 wasn’t the last major OS update

Microsoft releases two major updates of its Windows operating system each year. Windows 10 was supposed to be the largest refresh before it moved to bi-annual updates, as Gartner research director Ranjit Atwal recalls.

“When Windows 10 came out after Windows 7, Microsoft, I’m sure, said it was going to be the last big operating system upgrade,” he says. “Effectively, Microsoft was saying there would be no Windows 11 after Windows 10, and we took that for gospel to mean that it would be the last upgrade.”

However, in a Computer Weekly YouTube video, Atwal points out that the success of the Windows operating system actually hinders progress.

“So much legacy software and peripherals are supported through the operating system. At some point, that’s just become too much in terms of the code and managing the updates,” he says.

What this implies is that, at some point, updates to device driver software will no longer be available. If a PC continues to run outdated device drivers, there is a risk that the old driver software could have a known vulnerability that is being exploited. Clearly, Microsoft is unwilling to coordinate the effort required to support device drivers indefinitely, which means that perfectly good peripherals will lose support eventually; they may still run using the older (legacy) device driver, but there will not be any newer versions (see box: MacOS end-of-life).

To discourage people from trying to continue using these device drivers, Windows 11 uses a feature called Secure Boot, which enforces signed device drivers. This means only software that has a current digital signature can be installed. But like many features in Windows, there are workarounds, and unless an IT department runs a fully locked-down PC environment, savvy end users can workaround the Secure Boot feature.

Moving to Windows 11

The NCSC says Windows 11 introduces a secure-by-default setup, which includes BitLocker, virtualisation-based security (VBS) and support for native passkey management. While some of these features were available in Windows 10, they are now switched on by default. “Devices that don’t meet Windows 11 hardware requirements – and are therefore unable to use the features that are needed to secure Windows – remain fundamentally vulnerable to attack,” the NCSC warns.

Among the benefits of migrating is the built-in artificial intelligence (AI) that Microsoft is promoting, which is available in Copilot+ PCs. AI PCs will represent 31% of the total PC market globally by the end of 2025, according to Gartner. The analyst firm’s latest forecast projects that worldwide shipments of AI PCs will total 77.8 million units in 2025.

By the end of 2026, Gartner expects 40% of software providers to prioritise investments in AI capabilities directly on PCs, up from 2% in 2024. In the same year, multiple small language models (SLMs) will run locally on PCs, up from zero in 2023.

Unlike five years ago, there is growing interest in using ARM-based hardware to support AI inference workloads on Windows 11. According to Microsoft, ARM-based PCs offer all-day battery life.

Gartner’s forecast shows that ARM-based laptops will gain a larger share of the consumer market than the business market, as application compatibility challenges are overcome. Its research found that business users prefer x86 PCs to run Windows. According to Gartner, the x86 PC market is expected to make up 71% of the AI business laptop market in 2025, with ARM making up 24%.

Discussing the forecast, Atwal says: “Businesses are evaluating ARM-based PCs to understand if it is a viable platform. The issue is that not all of the applications they need run on ARM at the moment, although the large majority of applications are ARM-compatible.”

Microsoft says applications need to be rebuilt to run natively on Windows ARM-based PCs. Applications that have not been rebuilt can be run using the Prism emulation that was shipped with Windows 11, version 24H2.

Atwal expects more native ARM applications to become available over the next 12 months. In particular, he sees an opportunity to use small language models directly on AI PCs, offering faster response times, lower energy consumption and reduced reliance on cloud services.

As Atwal notes, SLMs provide task-specific intelligence. “Since the AI runs directly on devices, SLMs help keep user and business data secure,” he adds.

Over time, the partnership between Qualcomm and Microsoft to deliver ARM-based Copilot+ PCs is likely to result in an enterprise alternative to x86-based Windows hardware.

“That partnership is driving ARM onto mainstream PCs, which is different to where we were maybe five years ago or 10 years ago when ARM hardware was around the edges,” says Atwal.

However, the support for new hardware and constant development of new and improved PC peripherals mean Microsoft will continue to be challenged with how much legacy software the Windows OS can support. From an IT management perspective, this means support for older hardware will continue to drop and IT leaders will continue to plan PC and operating system refreshes to ensure their PC estate remains current.