Business

The true cost of cyber hacking on businesses

Theo LeggettInternational Business Correspondent

Theo LeggettInternational Business Correspondent BBC

BBCThe first day of September should have marked the beginning of one of the busiest periods of the year for Jaguar Land Rover.

It was a Monday, and the release of new 75 series number plates was expected to produce a surge in demand from eager car buyers. At factories in Solihull and Halewood, as well as at its engine plant in Wolverhampton, staff were expecting to be working flat out.

Instead, when the early shift arrived, they were sent home. The production lines have remained idle ever since.

Though they are expected to resume operations in the coming days, it will be in a slow and carefully controlled manner. It could be another month before output returns to normal. Such was the impact of a major cyber attack that hit JLR at the end of August.

It is working with various cyber security specialists and police to investigate, but the financial damage has already been done. Over a month’s worth of worldwide production was lost.

Analysts have estimated its losses at £50m per week.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor a company that made a £2.5bn profit in the last financial year, and which is owned by the Indian giant Tata Group, the losses should be painful but not fatal. But JLR is not an isolated incident.

So far this year there has been a wave of cyber attacks targeting big businesses, including retailers such as Marks & Spencer and the Co-op, as well as a key airport systems provider. Other high profile victims have included the children’s nursery chain Kido, while last year incidents involving Southern Water and a company that provided essential blood tests to the NHS raised serious concerns about the vulnerability of critical infrastructure and services.

In all, a government run survey on cyber security breaches estimates 612,000 businesses and 61,000 charities were targeted across the UK. So just how much are attacks like these costing businesses and the economy?

And could it be, as one expert analyst puts it, that this year’s major attacks are the result of a “cumulative effect of a kind of inaction” on cyber security from the government and businesses that is now starting to bite?

Pyramid of suppliers affected

What is significant about an attack on the scale of the one that hit JLR is just how far the consequences can stretch.

The company sits at the top of a pyramid of suppliers, thousands of them. They range from major multinationals, such as Bosch, down to small firms with a handful of employees, and they include companies which are heavily reliant on a single customer: JLR.

For many of those firms, the shutdown represented a very real threat to their business.

In a letter to the Chancellor on 25 September, the Business and Trade Committee warned that smaller firms “may have at best a week of cashflow left to support themselves”, while larger companies “may begin to seriously struggle within a fortnight”.

Industry analysts expressed concerns that if companies started to go bankrupt, a trickle could soon become a flood – potentially causing permanent damage to the country’s advanced engineering industry.

Resuming production does not automatically mean the crisis is over either.

“It has come too late,” explains David Roberts, who is the Chairman of Coventry-based Evtec, a direct supplier to JLR, with some 1,250 employees.

“All of our companies have had six weeks of zero sales, but all the costs. The sector still desperately needs cash.”

From Co-op to Marks & Spencer

A recent IBM report, which looked at data breaches experienced by about 600 organisations worldwide found that the average cost was $4.4m (or £3.3m).

But JLR is far from an outlier when it comes to high-profile cyber attacks on an even greater scale. Marks & Spencer and the Co-op supermarket chain this year are estimated to have cost £300 million and £120 million respectively.

Over the Easter weekend in April, attackers managed to gain entry to Marks & Spencer’s IT systems via a third-party contractor, forcing it to take some networks offline.

Initially, the disruption seemed relatively minor – with contactless payment systems out of action, and customers unable to use its ‘click and collect’ service. However, within days, it had halted all online shopping – which normally makes up around a third of its business.

It was described at the time as “almost like cutting off one of your limbs”, by Nayna McIntosh, former executive committee member of M&S and the founder of Hope Fashion.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty ImagesWhen the Co-op supermarket chain was hit, the same group of hackers claimed responsibility.

It was, they suggested, an attempt to extort a ransom from the company by infecting its networks with malicious software. However the IT networks were shut down quickly enough to avoid significant damage.

As the criminals angrily described it to the BBC, “they yanked their own plug – tanking sales, burning logistics, and torching shareholder value”.

According to Jamie MacColl, a cyber expert at the security research group, the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), it is no surprise to see major businesses being targeted in this way.

He says it is the result of hackers being easily able to get hold of so-called ransomware (software which can lock up or encrypt a victim’s computer networks until a ransom is paid).

“Historically, this kind of cyber crime… has mostly been carried out by Russian-speaking criminals, based in Russia or other parts of the former Soviet Union”, he explains.

“But there’s been a bit of a change in the last couple of years where English-speaking, mostly teenage hackers have been leasing or renting ransomware from those Russian-speaking cyber criminals, and then using it to disrupt and extort from the businesses they’ve gained access to.

“And those English-speaking criminals do tend to focus on quite high-profile victims, because they’re not just financially motivated: they want to demonstrate their skill and get kudos within this quite nasty sort of hacking ecosystem that we have.”

Weak spots of big business

What makes companies like Jaguar Land Rover and Marks & Spencer particularly vulnerable is the way in which their supply chains work.

Carmakers have a long tradition of using so-called “just-in-time delivery”, where parts are not held in stock but delivered from suppliers exactly where and when they are needed.

This cuts down on storage and waste costs. But it also requires intricate coordination of every aspect of the supply chain, and if the computers break down, the disruption can be dramatic.

Likewise, a retailer like Marks & Spencer relies on a carefully coordinated supply chain to guarantee customers the right quantities of fresh produce in the right places – which similarly proves vulnerable.

Reuters

Reuters“Other industries have this model too: electronics and high-tech, because it’s expensive and risky to hold inventory for a long time due to obsolescence. And then other industrial firms, such as in aerospace, for similar reasons to automotive,” explains Elizabeth Rust, lead economist at Oxford Economics.

“So they’re a bit more vulnerable to supply chain disruption from a cyber attack.”

But she points out this is not the case for industries such as pharmaceuticals, where regulators require firms to hold minimum levels of stock.

Rethinking lean production

Andy Palmer, a former chief executive of Aston Martin who has spent decades working in the manufacturing sector, thinks the lean production models in the car and food industries need a rethink.

It is a major risk, he says, when you have “these systems where everything is tied to everything else, where the waste is taken out of every stage… but you break one link in that chain and you have no safety.

“The manufacturing sector has to have another look at the way it tackles this latest black swan”, he says, referring to an event that is unforeseen but which has significant consequences.

But according to Ms Rust, businesses are unlikely to change the way their supply chains operate.

“Cyber attacks are really expensive… but shifting away from just-in-time management is potentially even more expensive. This is hundreds of millions, possibly, that a firm would have to incur annually”.

She believes the costs would also make it a steep challenge for regulators to demand such changes.

‘The cumulative effect of inaction’

In late September a ransomware attack on American aviation technology firm Collins Aerospace caused serious problems at a number of European airports, including London Heathrow, after it disabled check-in and baggage handling systems.

The problem was resolved relatively quickly, but not before a large number of flights had been cancelled.

Industry sources warn that Europe’s airspace and key airports are so heavily congested that disruption in one area can quickly spread to others – and the costs can quickly add up.

In this instance, the knock-on effects were largely confined to widespread delays and flight cancellations. But it nods to a bigger question of what happens if a hack on critical infrastructure paralyses financial, transport or energy networks, potentially leading to huge economic costs – or worse?

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images“I think the worst-case scenario is probably something affecting financial services or energy provision, because of the potential cascading effects of either of those two”, says RUSI analyst Jamie MacColl.

“The good news is the financial sector is by far the most heavily-regulated sector in the UK for cyber security. And I think it’s quite telling, there’s rarely been a very impactful cyber attack on a Western bank.”

The outlook, were there an attack on the energy sector, is not clear.

A 2015 study by Lloyds Bank, entitled “Business Blackout”, modelled the impact of a hypothetical attack on the US power grid, concluding that economic losses could exceed $1 trillion (£742bn). However Mr MacColl believes that in the UK, there is probably enough spare capacity in the grid to deal with a cyber incident.

More concerningly, Mr MacColl thinks the UK has had “quite a laissez-faire approach to cyber security over the past 15 years”, with the issue given little priority by successive governments.

He believes that this year’s major attacks may be the “cumulative effect of a kind of inaction on cyber security, both from the government and from businesses, and it’s sort of really starting to bite now”.

That inaction, he says, needs to change, with both regulators and large businesses taking more responsibility.

Anadolu via Getty Images

Anadolu via Getty ImagesIn July last year the government did announce plans to introduce a Cyber Security and Resilience bill but its passage to becoming law has been repeatedly delayed.

In May, GCHQ’s National Cyber Security Centre published a report warning about the growing impact of cyber threats from hackers using artificial intelligence-based tools. It suggested that over the next two years, “a growing divide will emerge between organisations that can keep pace with AI-enabled threats, and those that fall behind – exposing them to greater risk, and intensifying the overall threat to the UK’s digital infrastructure.

However, what worries Jamie MacColl most are the sorts of attacks we haven’t yet thought to protect against.

“I would be more concerned about the sort of company that is the only business that provides a particular service, but that we don’t really know about, and that isn’t regulated as critical national infrastructure”, he says.

An attack on one of these less glamourous economic pivots, he argues, could have huge ramifications through the wider economy.

“That’s the sort of thing that would keep me up at night,” he says. “The single point of failure that we are not aware of yet.”

Top image credit: PA

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Business

HSBC reclaims top spot as FTSE 100 hits new high

The FTSE 100 reached fresh heights on Wednesday, with well-received results from HSBC, and gains in mining stocks, paving the way for another record-breaking day.

“The strong showing from the UK stock market so far in 2026, on top of a major success in 2025, bodes well for changing its reputation from unloved to admired,” said Russ Mould, investment director at AJ Bell.

The FTSE 100 index ended up 125.82 points, 1.2%, at 10,806.41, a record close and its best level for the day.

The FTSE 250 ended up 135.85 points, 0.6%, at 23,636.89, and the AIM All-Share closed up 1.26 points, 0.2%, at 816.79.

London’s brighter mood was reflected elsewhere in Europe.

The CAC 40 in Paris closed up 0.5% on Wednesday, while the DAX 40 in Frankfurt ended 0.8% higher.

Stocks in New York were also higher. The Dow Jones Industrial Average was up 0.4%, the S&P 500 index was 0.6% higher, and the Nasdaq Composite advanced 1.0%.

Across the pond all eyes point towards earnings from Nvidia, due for release after the New York market close.

David Morrison, senior market analyst at Trade Nation, said: “Tonight’s results will focus initially on revenues and earnings. In prior quarters, Nvidia has often surprised investors with bullish forward guidance, and if there’s good news here, then that should underpin the share price.

“But data centre revenue, chip demand and hyperscale cloud spending are all important elements, while competition (another recent issue) and margins will also be poured over by analysts.”

The pound was little changed at 1.3537 dollars on Wednesday afternoon, from 1.3536 dollars at the equities close on Tuesday.

The euro stood higher at 1.1804 dollars, from 1.1787 dollars. Against the yen, the dollar was trading higher at 156.39 yen, compared with 155.71 yen.

The yield on the US 10-year Treasury widened to 4.05% on Wednesday from 4.04% on Tuesday. The yield on the US 30-year Treasury was flat at 4.69%.

In London, shares in HSBC hit an all-time high after better-than-expected fourth-quarter results.

The 7.9% gain took the Asia-focused lender’s market value to £239.29 billion, overtaking AstraZeneca as the most valuable listed UK company.

Cambridge-based drugs firm AstraZeneca has a market value of a touch below £236 billion after falling 0.7% on Wednesday, with oil major Shell, up 1.3%, a distant third at £169.72 billion.

For the fourth quarter of 2025, HSBC said adjusted pre-tax profit rose to 8.59 billion dollars from 7.32 billion dollars a year ago, ahead of 7.85 billion dollars consensus.

JPMorgan said the profit beat was driven by strong banking net interest income, and impairments coming in 12% lower than forecast.

Looking ahead, chief executive Georges Elhedery said HSBC is “raising our ambition and targeting a 17% [return on tangible equity] or better, excluding notable items, in each year from 2026 to 2028”.

“We are also targeting year-on-year revenue growth over the same period on the same basis, rising to 5% in 2028,” he added.

JPM said the new targets are slightly above consensus expectations for annual revenue growth of 4.2% in 2028.

Citi analyst Andrew Coombs said it was “a good print”, with “potential for high-single digit consensus EPS upgrades”.

Mining stocks were also in demand as metals prices rose.

Gold firmed to 5,204.64 dollars an ounce on Wednesday from 5,142.02 dollars on Tuesday. Silver rose 4.1% and copper gained 0.9%.

Miners Fresnillo, Antofagasta and Anglo American rose 7.3%, 5.7% and 4.4% respectively.

Also in the green was St James’s Place, after it said it will increase shareholder returns after reporting better-than-expected 2025 results.

The London-based asset manager rose 6.6%, as it reported a post-tax underlying cash result of £462.3 million in 2025, up 3.4% from £447.2 million the year prior, and ahead of £445.5 million company-compiled consensus. Pre-tax profit increased 28% to £1.34 billion from £1.05 billion.

Post-tax underlying cash basic earnings per share of 87.0 pence, increased 6.1% from 82.0p, ahead of 84.2p consensus.

In addition, the firm intends to increase total annual shareholder distributions to 70% (from 50%) of the underlying cash result through a combination of dividends and share buy-backs.

But Diageo shareholders had a day to forget, as shares plunged 13% after it cut full-year sales guidance and slashed its dividend.

London-based Diageo operates in more than 180 countries with a portfolio of more than 200 brands, including top sellers such as Johnnie Walker whisky, Smirnoff vodka, Tanqueray gin and Guinness stout.

It said net sales fell 4.0% year-on-year to 10.46 billion dollars in the six months to December 31, from 10.90 billion dollars a year ago, below VA consensus of 10.57 billion dollars.

Sales declined 2.8% on an organic basis, compared to VA consensus for a 2.0% drop, with organic volumes down 0.9% and a negative price/mix of 1.9%.

“Trading conditions remained challenging in the first half of the year. We believe this was largely due to further macroeconomic and geopolitical uncertainty, and weak consumer confidence in key markets,” the company said in a statement.

For the financial year, Diageo now expects a full-year organic net sales decline of 2% to 3%, “given further weakness in the US”. It had previously predicted an outcome between “flat to slightly down”.

In addition, the firm halved its first-half payout to 20 cents per share from 40.50 cents a year prior.

New chief executive Dave Lewis said he is “confident that this is the right action” to “drive stronger shareholder value over the coming years”.

Dan Coatsworth, head of markets at AJ Bell, said: “There is no point trying to dress up the six-month figures. These are awful results, and the repair job is massive.”

On the FTSE 250, Trainline shares buckled as chief executive Jody Ford signalled his departure.

Shares in the London-based digital rail and coach ticketing platform fell 7.5%, as it said Mr Ford intends to step down as chief executive after more than six years at the company.

A formal search process to find his successor has begun, the firm added.

Brent oil traded lower at 70.76 dollars a barrel on Wednesday afternoon, from 71.16 dollars late Tuesday.

The biggest risers on the FTSE 100 were HSBC, up 102.60p at 1,394.00p, Metlen Energy & Metals, up 2.70p at 37.65p, Fresnillo, up 294.00p at 4,326.00p, St James’s Place, up 83.50p at 1,343.00p and Relx, up 142.00p at 2,415.00p.

The biggest fallers on the FTSE 100 were Diageo, down 238.00p at 1,636.00p, Haleon, down 27.80p at 377.90p, Croda, down 99.00p at 3,113.00p, Babcock International, down 29.00p at 1,374.00p and Tesco, down 8.30p at 492.20p.

Thursday’s global economic calendar has US initial jobless claims data.

Thursday’s domestic corporate calendar has full-year results from jet engine maker Rolls-Royce, advertising agency WPP, exchange operator and data provider London Stock Exchange and kitchen supplier Howden Joinery.

Contributed by Alliance News

Business

Restaurant reservation wars heat up as DoorDash enters the arena with Resy, OpenTable

Now available on your favorite food delivery app: restaurant reservations.

The still-simmering reservation wars of the last decade could fully reignite this year, as a shifting tech landscape pits some of the biggest players against each other to capture businesses and users alike. Reservation incumbents, delivery app newcomers and premium credit card partnerships are all ramping up the fight for a shrinking pool of diners.

Delivery giant DoorDash announced in June its $1.2 billion acquisition of SevenRooms, a reservation platform focused on direct bookings through a restaurant’s own website. Several months earlier, UberEats and Booking Holdings’ OpenTable announced a partnership to integrate reservations on Uber’s app. And in 2024, American Express, already the owner of Resy, bought Tock, a reservation platform focused on upscale restaurants, for $400 million.

“It’s three very large, very ambitious, very well-resourced companies all vying for the same exact piece of real estate, which is high-demand restaurants,” Resy and Eater founder Ben Leventhal told CNBC.

Resy was bought by AmEx in 2019, and today Leventhal — a strategic advisor for Resy until 2022 — focuses on Blackbird Labs, a loyalty program for independent restaurants that he founded that same year.

Bringing restaurants online

The reservation wars initially kicked off more than 10 years ago. Leventhal’s Resy burst onto the scene in 2014 and won market share, undercutting OpenTable’s legacy business, by charging eateries a simple monthly fee.

At the time, OpenTable, which was founded in 1998, charged restaurants both a monthly fee and a cover for each diner who booked through the platform. These days, the company still sometimes charges a variable cover fee for seated diners, depending on the establishment.

Thomas Barwick | Digitalvision | Getty Images

Despite Resy’s rise and buzzy partnerships with high-profile restaurants, OpenTable still significantly outstrips its rival by restaurant count.

Starting this summer, Resy will integrate the 5,000 eateries, bars and wineries that have listed on Tock onto its own platform, bringing its total number of venues to about 25,000. That’s still less than half of OpenTable’s roughly 60,000 restaurants.

But where OpenTable has scale, Resy has a “cool factor” and strong positioning in major cities, like New York, where dining out is big business.

And each companies’ relationships with credit card companies has added a new layer to the war, too.

Supercharging the platforms

Platinum American Express cardholders get special access to restaurant reservations at sought-after establishments, plus a $400 dining credit per year to use at Resy restaurants.

“We know that American Express card members spend close to $90 billion a year … on dining, and it’s a passion area for them,” Resy CEO Pablo Rivero told CNBC. “And we know that they also spend more. People with a Resy credit on an American Express card spend over 25% more on dining transactions.”

Likewise, eligible Visa and Chase cardholders get exclusive OpenTable reservations.

Those partnerships have also helped the legacy player woo some big-name restaurants away from Resy through cash incentives made possible by the credit card companies.

Recapturing top-tier restaurants with Michelin stars or James Beard awards has been a priority for OpenTable over the last five years, said OpenTable CEO Debby Soo.

“Credit card companies are looking for a perk to differentiate their cards, especially for their premium cardholders,” Soo said. “Especially after Covid, the experiential has become even more important.”

Delivery’s here

Now, DoorDash is entering the fray with its SevenRooms acquisition.

The company is used to fighting for market share in a competitive industry. Before the pandemic, DoorDash was up against UberEats and Grubhub for market dominance of online third-party food delivery.

As of 2025, DoorDash was the biggest player in the U.S. market, with about 67% share, according to digital restaurant operations firm Deliverect. UberEats trails with a 23% share.

Eric Baradat | AFP | Getty Images

As it enters the bookings game, DoorDash is looking to capture the range of dining possibilities, whether it’s delivery, takeout or table.

In the early months of its reservations integration, the platform was offering users DoorDash cash per booking to use on future delivery orders. And in select cities, it offers exclusive tables at trendy spots for members of DashPass, its subscription service.

Above all, the integration with SevenRooms gives DoorDash and its restaurants access to more data about diners.

“Delivery and dine-in have typically been siloed data sets,” SevenRooms co-founder Joel Montaniel said. “So if a customer has ordered six times, and they’re coming into the restaurant for the first time, are they a first-time customer or a seventh-time customer?”

Following a diner across touchpoints means a better experience, and more tailored marketing, he said.

“We’re seeing the flywheel happening and the excitement about the DoorDash reservation marketplace happening, but it’s still early days,” said Parisa Sadrzadeh, vice president of strategy and operations for DoorDash. “We’ve got a lot of room to continue to grow.”

Correction: This story has been updated to correct that Ben Leventhal was a strategic advisor to Resy until 2022.

Business

Ajit Jain: Warren Buffett’s trusted executive Ajit Jain buys apartment in Gurugram for Rs 85 crore – The Times of India

A 7,400 sq ft apartment at DLF The Camellias in Gurugram has been purchased by Berkshire Hathaway’s Ajit Jain. The vice-chairman overseeing insurance operations at Berkshire Hathaway, Ajit Jain, is regarded as one of Warren Buffett’s most trusted associates. The apartment has been bought for around Rs 85 crore, according to sources quoted in an ET report.Jain, who has spent most of his time living abroad, recently visited Delhi to complete the deal, the sources said. One person aware of the development said non-resident Indians account for more than 25% of DLF’s ultra-luxury housing portfolio, and Jain is among the most prominent buyers in this segment. The individual added that premium amenities offered at such developments are a major attraction for those who plan to spend only part of the year in India. Jain is widely considered one of the most influential Indian-origin business leaders in the United States.Property consultants noted that since the Covid period, ultra-high-net-worth individuals have increasingly favoured secure, gated condominium projects over independent bungalows, as such residences provide access to a wide range of on-site facilities.ET recently reported that an industrialist purchased four apartments at DLF’s new ultra-luxury project, The Dahlias, for close to Rs 380 crore, making it one of the country’s most expensive apartment transactions.In 2025, Gurugram saw the costliest property deal in the National Capital Region, overtaking Lutyens’ Delhi for the first time. Prices per square foot in the city have surpassed those in Mumbai and reached levels comparable with London and Dubai. Earlier, British entrepreneur Sukhpal Singh Ahluwalia had acquired an 11,416 sq ft apartment in the same project for Rs 100 crore.Info-x Software Technology, through its director Rishi Parti, had also purchased a 16,000 sq ft penthouse for Rs 190 crore.In October 2023, ET reported the first Rs 100-crore transaction at the same residential complex on Gurugram’s Golf Course Road.

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoQueen Camilla reveals her sister’s connection to Princess Diana

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoRakuten Mobile proposal selected for Jaxa space strategy | Computer Weekly

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoRamadan moon sighted in Saudi Arabia, other Gulf countries

-

Entertainment1 week ago

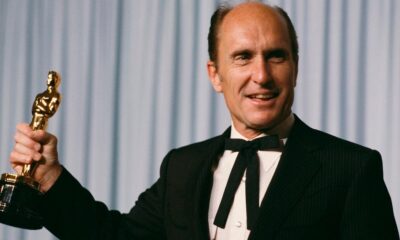

Entertainment1 week agoRobert Duvall, known for his roles in "The Godfather" and "Apocalypse Now," dies at 95

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoTax Saving FD: This Simple Investment Can Help You Earn And Save More

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoTarique Rahman Takes Oath as Bangladesh’s Prime Minister Following Decisive BNP Triumph

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoBusinesses may be caught by government proposals to restrict VPN use | Computer Weekly

-

Fashion1 week ago

Fashion1 week agoAustralia’s GDP projected to grow 2.1% in 2026: IMF