Entertainment

Princess Beatrice sees future crumble around her after Prince Andrew, Sarah Ferguson

Princess Beatrice has been hit pretty hard with her father Prince Andrew and mom Sarah Ferguson’s personal woes.

So much so that her chances at a royal future are also looking bleak, according to a well placed source.

This insider shared everything with Heat World during a candid chat and explained that while “the King was previously open to striking some type of compromise with Beatrice especially, one that would see her take on more royal responsibility and potentially ease herself back towards a full-time working position within the family.”

Now “that can’t possibly happen”, because there are many who “would believe it would be rewarding her father by association and the consensus is that a clean cut with the Yorks”.

So as it stands, “as far as business and formal invites at the very least – is what’s necessary.”

For those unversed with the issues plaguing the Yorks, after his late accuser Virginia Giuffre tied Prince Andrew with the convicted sex offender, his ex-wife Sarah was also revealed to have emailed him a written apology after publically denouncing his actions, out of fear of a lawsuit.

According to the source, “this is horrible for the girls, it’s all crumbling around them so quickly and dramatically.”

“This is just heart-breaking for them and they’re very upset with their mother and father, quite rightly so,” she said while signing off.

Entertainment

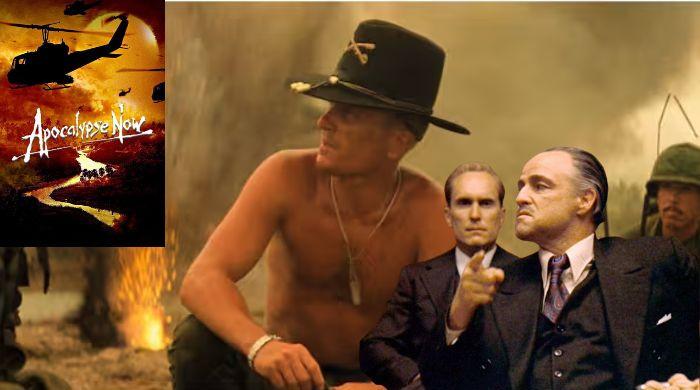

Why Robert Duvall’s ‘napalm’ line in ‘Apocalypse Now’ is so iconic

One of the most referenced and iconic dialogues in the history of cinema that truly enjoyed a life of its own is “I love the smell of napalm in the morning.”

These timeless lines were performed by Robert Duvall in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 Vietnam War classic Apocalypse Now.

The chilling monologue is what is making buzz on social media again after the demise of the Oscar winner for Tender Mercies, who passed away at his home in Middleburg, Virginia, on Sunday, February 15.

Let’s find out why, decades later, the monologue has become one of the most quoted lines in cinema history.

The line was said by Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore, a daring and eccentric cavalry officer, when he set a helicopter ambush on a Vietnamese village.

Colonel Kilgore calmly reflects on the ashes left after the napalm bombing, finally coming to terms with the fact that it smells like “victory.”

The line is, “Napalm, son. Nothing else in the world smells like that. I love the smell of napalm in the morning. You know, one time we had a hill bombed for twelve hours. When it was all over, I walked up. We didn’t find one of ‘em, not one stinking drink body.

“The smell, you know, the gasoline smell, the whole hill. Smelled like… victory.”

What follows is, “Some day this war’s gonna end.”

It was a quiet introspection of what war takes and steals from human lives.

Why does the line continue to resonate?

The dialogue has taken on a life beyond the film, becoming a symbol for glorifying chaos, dark irony, and battlefield arrogance.

Cultural critics have been referencing it across pop culture, memes, viral trends, and television shows, often using it with a taste of sarcasm to introspect obsession, destruction, or self-indulgence.

Above all, Robert Duvall’s iconic performance in the film, especially in the immortal sequence, has been etched into the memories of cinema lovers, as long as the shadows of war continue to loom over our planet.

Entertainment

Chinese ‘Year of Fire Horse’ to bring luck for Mamdani, challenges for Trump

China has welcomed its Lunar New Year with nationwide celebrations of fireworks, lanterns, and festivities.

2026 is the Year of the Fire Horse, which symbolises power and speed.

A feng shui expert Raymond Lo has made predictions on how the new year will be for prominent American personalities, including the United States (U.S.) President Donald Trump, New York Mayor Zohran Mamdani and Hollywood sensation Timothee Chalamet.

For context, a Feng Shui Master is a professional, often rooted in traditional Chinese metaphysics, who interprets and manipulates environmental energy (Qi) to enhance harmony, health, and prosperity in homes and businesses.

In an interview with CNN, Master Lo said, “The horse represents a powerful fire element. So it’s a pure fire year. Fire is very strong and very energetic.”

He added that it will bring protests and anti-government demonstrations in the U.S. that could not be so peaceful, adding, “Fire is not a favourable element for President Trump, so it will stimulate his enemies.”

Master Lo said Trump will likely face fierce opposition and significant obstacles in the year of the fire horse.

The year is predicted to be favourable for New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani, who was sworn-in last year after winning the election against political heavyweights.

Master Lo said, “Mamdani has a strong metal element in his chart, and fire is a power to metal people. He will gain power. It’s a very favourable year for him.”

The predictions don’t always come true as Master Lo’s prediction about then-President Biden having a good year in 2024 and Trump having a bad year did not come true, as Trump went on to win the 2024 presidential election despite Lo’s forecast.

Entertainment

Police identify shooter Robert Dorgan, say attack tied to family dispute

Police have identified the shooter in the Pawtucket ice rink shooting that left three dead. Officials said the suspect, Robert Dorgan, who also went by the name of Roberta Esposito, has allegedly died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

On Monday afternoon, February 16, 2026, at around 2:30 p.m., a lone shooter opened fire on people in a local skating rink, Dennis M. Lynch Arena, in Pawtucket, Rhode Island and killed three people while leaving three others in critical condition.

Pawtucket Police Chief Tina Goncalves stated the said authorities have not yet released the victims’ identities. She said that the shooting appears to be targeted, adding, “It may have been a family dispute.”

The unfortunate incident occurred during a high school hockey game between Coventry/Johnston and Blackstone Valley Co-op.

Witnesses described the horrific scenes and confusion after the tragic shooting as the spectators and players ran to seek shelter and flee towards the exit.

Melissa Dunn, the mother of one of the players, said, “It was supposed to be a special day for the team, and it’s really sad.”

A sophomore goalkeeper from Coventry High School, Olin Lawrence, described the situation as complete chaos, saying, “We ran to the locker room and just tried to be safe. We pressed against the door and just tried to stay safe down there. It was very scary. We were very nervous. There were a lot of shots.”

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoAye Finance IPO Day 2: GMP Remains Zero; Apply Or Not? Check Price, GMP, Financials, Recommendations

-

Fashion7 days ago

Fashion7 days agoComment: Tariffs, capacity and timing reshape sourcing decisions

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoRemoving barriers to tech careers

-

Entertainment7 days ago

Entertainment7 days ago‘Harry Potter’ star David Thewlis doesn’t want you to ask him THIS question

-

Fashion7 days ago

Fashion7 days agoADB commits $30 mn to support MSMEs in Philippines

-

Fashion7 days ago

Fashion7 days agoSaint Laurent retains top spot as hottest brand in Q4 2025 Lyst Index

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoWinter Olympics opening ceremony host sparks fury for misidentifying Mariah Carey, other blunders

-

Fashion4 days ago

Fashion4 days ago$10→ $12.10 FOB: The real price of zero-duty apparel