Business

Minister defends ‘pragmatic’ U-turn on workers’ rights

Paul SeddonPolitical reporter

PA Media

PA MediaThe education secretary has defended Labour’s U-turn over offering all workers the right to claim unfair dismissal from their first day in a job.

Instead, ministers now plan to reduce the qualifying period from the current two years to six months, in line with a deal agreed by some unions and industry groups.

Bridget Phillipson told the BBC the climbdown was a “pragmatic” move to ensure “wider benefits” in Labour’s employment rights bill could be delivered on time.

The decision has been welcomed by business organisations, but has faced criticism from some MPs on the left of the Labour Party.

Currently, after two continuous years in a job workers gain additional legal protections against being sacked.

Employers must identify a fair reason for dismissal – such as conduct or capability – and show that they acted reasonably and followed a fair process.

Under Labour’s original plan, this qualifying period would have been abolished completely, with a new legal probation period, likely to have been nine months, introduced as a safeguard for companies.

But business groups argued the plan could prove unworkable, and voiced concerns that day-one unfair dismissal rights would discourage firms from hiring.

In a surprise announcement on Thursday, the government confirmed it will now bring in unfair dismissal protection after six months, and ditch the new legal probation period.

‘Big step forward’

Ministers are continuing to insist the move does not breach Labour’s general election manifesto – even though the document clearly commits the party to creating “basic rights from day one to parental leave, sick pay, and protection from unfair dismissal”.

When the Commons debated the employment bill in September, Business Secretary Peter Kyle told MPs: “We were elected on a manifesto to provide protection from unfair dismissal from day one of employment”.

But on Thursday, he said the move was not a breach, since the party had also committed to “bring people together” over the issue.

The minister, who is responsible for Labour’s employment legislation, also argued it was “not my job to stand in the way” of an agreed approach brokered between some unions and business groups.

Ministers are also arguing the U-turn would unblock the passage of its wider employment rights bill through Parliament.

But former Employment Minister Justin Madders said he was “a little concerned” the government u-turn on unfair dismissal rights from day one of employment could open the door to further watering down of the bill.

The Labour MP, who lost his ministerial job in the September reshuffle, said: “I do appreciate there has to be some compromise but equally I’m not convinced we’ve done everything we can to stay true to our manifesto commitments and deliver the workers rights agenda in full.”

Conservative and Liberal Democrat peers have twice teamed up with crossbenchers in the House of Lords to insist on a six-month period instead, delaying its progress.

The Conservatives have said the legislation is “still not fit for purpose”, whilst the Lib Dems said the law had been “rushed and mired in problems from the get-go”.

Speaking to BBC Radio 4’s Today programme, Phillipson said the deadlock over unfair dismissal could have “jeopardised” the bill, which also contains new worker benefits, such as immediate rights to sick pay and paternity leave.

The move to lower the unfair dismissal qualifying period from two years to six months was still a “big step forward,” she added.

“Sometimes in life, you have to be pragmatic to secure wider benefits”.

‘Absolutely a breach’

The U-turn was universally welcomed by groups representing British industry, who had warned that fears over day-one dismissal rights had led to a stall in hiring new workers.

Martin McTague, national chair of the Federation of Small Businesses, said: “I can’t emphasise too much that this part of the bill was the most important thing to put right.”

So far, the reaction to the manifesto breach has been reserved to MPs on the left Labour Party.

However, the Labour leadership will be less comfortable if former deputy PM Angela Rayner – the architect of the initial proposals – expresses criticism. She has not responded to requests for comment.

The U-turn has received an angry reaction from the Unite union, a major Labour donor through the affiliation fees its members pay to the party.

The union’s boss Sharon Graham told the BBC it was “absolutely a breach” of the party’s election manifesto, adding she feared “further watering down” of the employment bill in the future.

The business department confirmed on Thursday that it still plans to bring in day-one sick pay and paternity leave rights from April 2026.

However, it is yet to confirm a start date for the new 6-month period, which it is understood will not be specified in the employment bill itself either.

It had previously committed to implementing the right from day one from 2027, under a “roadmap” unveiled over the summer.

The government does not need to pass the employment rights bill to change the qualifying period – it already has powers to do this under existing legislation, which the coalition government used in 2012 to up the period to the current two years.

But writing the changes into a full Act of Parliament was meant to prevent the new rights being easily unpicked by a future government.

On Thursday, the business department said it was still committed to doing this, as a means to “further strengthen” the new protections.

Business

Reliance Industries Q3 Results: Revenue Rises 10% On Digital, Oil-To-Chemicals Growth

Last Updated:

Reliance Industries Q3 FY26 Financial Results | Earnings remained resilient during the December quarter despite pressure in upstream oil & gas exploration and production business.

Reliance Industries Q3 Results.

Reliance Industries Ltd reported a resilient performance in the fiscal third quarter, with consolidated revenue rising 10 percent from a year earlier to Rs 2.94 lakh crore, led by growth in its digital services, oil-to-chemicals (O2C) and retail businesses.

Net profit (pre minority) for the fiscal third quarter rose 1.6 percent from a year earlier to Rs 22,290 crore, while profit before tax increased 3.7 percent to Rs 29,697 crore.

Consolidated EBITDA rose 6.1 percent to Rs 50,932 crore, supported by earnings growth in the digital services and O2C segments, helping offset weakness in the upstream oil and gas business.

“Reliance’s consolidated performance in 3Q FY26 reflects consistent financial delivery and operational resilience across businesses,” said Mukesh Ambani, Chairman and Managing Director, Reliance Industries Ltd, in a statement on Friday.

The O2C business benefited from a sharp increase in transportation fuel cracks, which rose 62-106 percent from a year earlier during the third quarter. This improvement was partly offset by lower downstream chemical margins and higher feedstock freight rates. Overall, O2C EBITDA rose 15 percent from a year earlier to Rs 16,507 crore, helped by higher volumes and a continued ramp-up in fuel retail operations.

The Jio-bp fuel retailing business maintained its growth momentum, with fuel volumes rising 24 percent, supported by strong growth in gasoline and high-speed diesel sales. The retail network expanded further, with Jio-bp operating 2,125 outlets at the end of December, a 14 percent increase from a year earlier.

“Robust growth in O2C business was led by significantly higher fuel margins with favorable demand-supply dynamics, along with operational flexibility. I am happy to highlight the strong growth in our fuel retailing business, with continuing expansion of the Jio-bp network,” Ambani added.

The digital services business delivered strong growth, with revenue rising 12.7 percent to Rs 43,683 crore. EBITDA from the segment grew 16.4 percent YoY to Rs 19,303 crore, aided by accelerated subscriber additions and a 170-basis-point expansion in margins.

Reliance Jio’s subscriber base increased to 515.3 million, with its 5G user base crossing 250 million during the quarter. Total home connects crossed 25 million, while JioAirFiber became the first fixed wireless access service globally to surpass 10 million subscribers, ending the quarter with 11.5 million users. Average revenue per user (ARPU) rose 5.1 percent from a year earlier to Rs 213.7.

“This quarter, Jio expanded its subscriber base further, through attractive propositions enabled by its comprehensive, indigenous technology stack tailored for Indian markets. The business delivered a robust financial performance with 16.4% growth in EBITDA,” said Ambani.

JioStar continued to report strong operational performance, maintaining leadership across key platforms and genres.

In contrast, the oil and gas business weighed on overall performance, affected by lower production from the KGD6 block due to natural decline in the reservoir and weaker price realisations, along with higher operating costs related to periodic maintenance activity. EBITDA declined 13 percent from a year earlier to Rs 4,857 crore. Revenue from the segment fell 8.4 percent to Rs 5,833 crore.

The retail business posted revenue of Rs 97,605 crore, an increase of 8.1 percent from a year earlier. Growth, however, was impacted by the distribution of festive demand between the September and December quarters, the demerger of Reliance Consumer Products Ltd, and GST rate rationalisation. Despite these, retail EBITDA rose to Rs 6,915 crore. During the quarter, Reliance Retail operated 19,979 stores, with a total operational area of 78.1 million sq ft, while hyper-local delivery operations saw a near fivefold jump in average daily orders.

“Our Retail business also had an eventful quarter, strengthening its portfolio with the onboarding of fresh new brands and product ranges. The demerger of consumer products business came into effect this quarter. With a broad and diverse product basket ranging from classic Indian brands to new age labels, the consumer products vertical is progressing on its accelerated growth trajectory with a focused organizational structure,” said Ambani.

During the quarter, capital expenditure stood at Rs 33,826 crore, which was fully covered by cash profits of Rs 41,303 crore. Net debt declined sequentially to Rs 1.17 lakh crore as of December 31, reflecting balance sheet stability.

Disclaimer:Network18 and TV18 – the companies that operate news18.com – are controlled by Independent Media Trust, of which Reliance Industries is the sole beneficiary.

January 16, 2026, 19:28 IST

Read More

Business

Budget 2026: Who Delivered The Longest Budget Speech In India?

New Delhi: Every year, the Union Budget draws nationwide attention as it outlines the government’s plans for the economy and public spending. Traditionally presented on February 1, the Budget will be tabled by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman on February 1, 2026, at 11 am, as confirmed by Lok Sabha Speaker Om Birla.

A Record-Breaking Budget Speech

Nirmala Sitharaman created history by delivering the longest Budget speech in India in 2020, which lasted 2 hours and 42 minutes. The marathon address introduced several major announcements, including a new income tax regime and the much-awaited initial public offering (IPO) of Life Insurance Corporation (LIC).

However, during the course of the speech, Sitharaman felt unwell, following which Lok Sabha Speaker Om Birla read out the remaining two pages on her behalf. Notably, the 2020 speech had already surpassed her own 2019 record, when she spoke for 2 hours and 17 minutes. In contrast, her 2024 Interim Budget speech was much shorter, lasting just 56 minutes, her briefest Budget address since taking charge as Finance Minister.

Understanding the Union Budget: What It Means for India

The Union Budget is a yearly financial statement presented by the Finance Minister in Parliament under Article 112 of the Constitution of India. It outlines the government’s estimated income and spending for the upcoming financial year, giving a clear picture of how public funds will be raised and used.

Along with revenue and expenditure details, the Union Budget also announces proposed changes in taxes, key focus areas for development, policy initiatives, and major economic reforms. It serves as a roadmap for the country’s economic direction in the year ahead.

Over the years, Budget speeches have evolved to reflect India’s changing economic needs and challenges. All eyes are now on Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman, who has been leading the Finance Ministry since 2019 and is set to present her eighth Union Budget on February 1.

Business

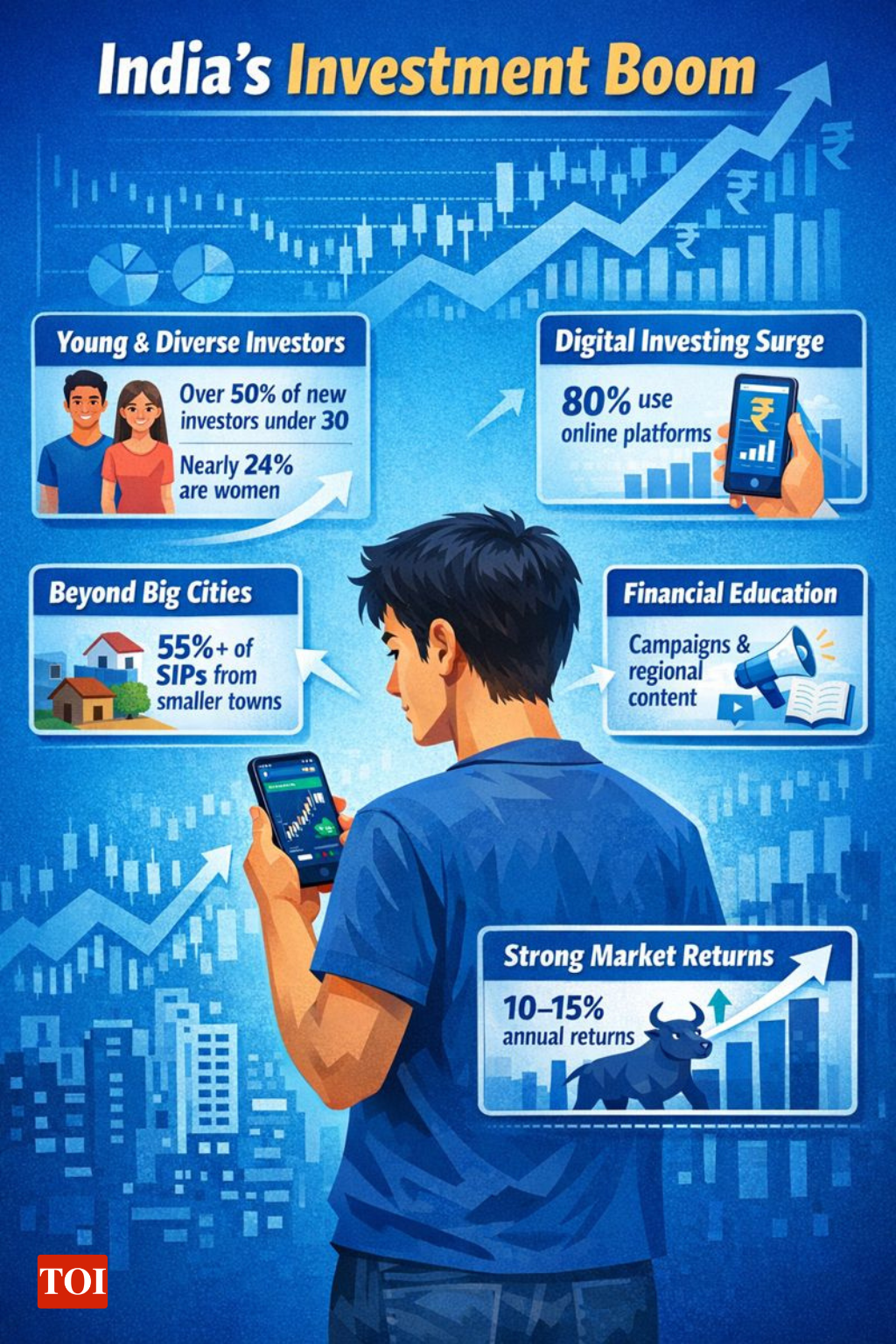

Fundamental shift from savers to investors: What Indian households are doing with their money? – The Times of India

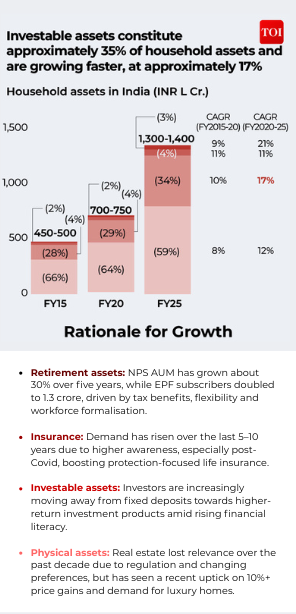

For years, Indian families have saved in gold, stored cash, and put money in tangible assets to safeguard their future. But now, there’s a noticeable shift is visible as more Indian households are moving away from old saving ways and putting their money to work through investments.India’s total household wealth, by the end of FY25, stood at Rs 1,300-1,400 lakh crore. Of this, investable financial assets stand at almost 35% of the total, growing at nearly 17% over the past five years, according to a recent Bain–Groww report, titled How India Invests.

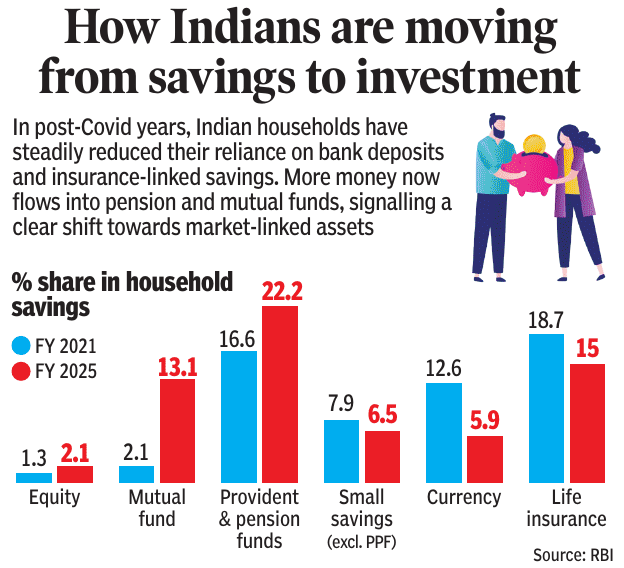

Household wealth has gone through a shift since the Covid era. Indians have moved from traditional fixed deposits toward market-linked instruments like mutual funds, pension funds and listed equities, which are growing at a fast rate, far outpacing deposits growth.Over the last five years, individual investor base in the country has expanded sharply, going from around 3 crore investors in 2019 to over 12 crore by 2025, according to the Market Pulse December 2025 report by the National Stock Exchange of India (NSE), India. In 2025 alone, households invested a whopping Rs 4.5 lakh crore into equity markets, both directly and indirectly through mutual funds. This, pushed the overall household investment in equities since 2020 to around Rs 17 lakh crore. In FY25, mutual fund assets under management (AUM) held by individuals reached Rs 41 lakh crore, driven by double participation by households, going from 5–6% to 10–11%, and increasing popularity of systematic investment plans (SIPs).According to RBI data, equity formed 1.3% of household savings in FY2021, but its share increased to 2.1% by FY2025. Similarly, mutual funds recorded a significant jump over the same period, with their share rising sharply from 2.1% to 13.1%. Contributions to provident and pension funds also grew, increasing from 16.6% in FY2021 to 22.2% in FY2025.In contrast, traditional savings instruments saw a decline. Small savings, excluding PPF, fell from 7.9% to 6.5%, while the share of currency in household savings dropped steeply from 12.6% to 5.9%. Life insurance also witnessed a reduction, with its share slipping from 18.7% in FY2021 to 15% in FY2025.Gradually, households reduced their dependence on bank deposits and insurance-based savings. Instead, investments in pension schemes and mutual funds have gathered pace, pointing to a broader shift towards market-linked financial products.

Mutual funds, stocks, SIPs: Who is choosing what?

Salaried households show a clear preference for mutual funds, particularly through SIPs, reflecting a tilt toward disciplined, professionally managed investing aligned with long-term financial goals, according to the Bain report. In contrast, business owners display a stronger inclination toward direct equity investments, marked by higher trading frequency and a greater appetite for risk. Within mutual funds, SIPs remain the dominant entry route, while lump-sum investments are steadily gaining traction as investors mature, build market confidence, and increase their risk tolerance.

Interest in investing spiked after Covid?

Covid didn’t just change daily life, it changed how Indians invest. Retail participation in the stock market rose sharply after the pandemic, driven by a mix of high liquidity, lower household spending during lockdowns and the flexibility of work-from-home, Rohit Shah, Certified Financial Planner and founder of Getting You Rich told TOI. Shweta Rajani, head of mutual funds at Anand Rathi Wealth Limited, pointed out that mutual funds made up only 4–5% of household financial assets between FY15 and FY20, but this share nearly doubled from around 5% in FY20 to close to 10% by FY25. At the same time, direct equity investments also grew sharply, rising from about 4% of household assets in FY20 to around 9% by FY25. “Together, these shifts indicate a clear move away from traditional savings instruments towards market-linked investments, indicating investors are comfortable with equity as an asset,” the expert added.Meanwhile, Nirav Karkera, head of research at Fisdom believes that Covid acted more as an accelerator than a starting point as the shift had already begun after demonetisation. The switch made Indians comfortable with digital payments and later with digital investing. By the time the pandemic arrived, systems such as Aadhaar-based KYC, easy online transactions and awareness campaigns like Mutual Fund Sahi Hai had removed most barriers. “When the pandemic hit, investors suddenly had the time and urgency to reflect on their personal finances. More importantly, the infrastructure to execute decisions with almost zero friction already existed. Willingness, ability and accessibility came together and translated into action. The sharp and mostly linear market recovery that followed further strengthened confidence, pulled in fence-sitters and accelerated the broader financialisation of household assets that was underway,” Nirav added.

Change in India’s risk appetite

India’s shift from saving to investing is being driven less by thrill-seeking and more by necessity, experts said. Traditional savings instruments are increasingly failing to protect wealth, as post-tax returns often fall below inflation, steadily eroding purchasing power. “What looks like rising risk appetite is partly a change in the understanding of risk itself,” said Karkera, adding that investors now see the risk of staying idle and falling behind as greater than the risk of market volatility. This shift has been reinforced by deeper financial awareness, easier access to investing through fintech platforms, and stronger regulation, said Rajani. The expert further noted that SIPs, simplified KYC and digital onboarding have lowered entry barriers, while a generational change is reshaping attitudes, older investors prioritised capital preservation, but younger earners, facing higher inflation and lower real interest rates, are more focused on long-term wealth creation using growth assets. However Shah cautioned that rising participation does not always mean better risk management. “Four structural factors drive this shift: financial literacy campaigns, fintech accessibility reducing entry barriers, higher equity allocations in mutual fund inflows, and rising per capita incomes. Yet risk appetite may be overstated. Data on retail trading patterns shows concentration in speculative segments, suggesting investors confuse market participation with risk management. Many haven’t weathered a bear market, leading to underestimation of downside volatility,” Shah told TOI.

Here’s what is driving the investors:

A combination of demographic change, regulatory support, digital access and strong market returns has accelerated India’s move from traditional savings to investing.

Demographic changesYounger investors are driving India’s shift from traditional savings to investing, with NSE data showing that more than half newly registered investors are below 30. At the same time, women are steadily increasing their presence in financial markets. As of November 2025, women account for nearly a quarter of India’s investor base, with their share in the NSE’s individual investor pool remaining stable at almost 24%.Digital transformationDigital platforms have emerged as the main entry point for retail investors in the country, with almost 80% of direct equity investors and around 35% of mutual fund investors investing through digital channels. According to the Bain report, driven by app-based onboarding, paperless KYC and fintech-led distribution, platforms such as Groww, Zerodha and Upstox have simplified investing, brought in millions of first-time investors, and together account for almost 80% of India’s retail equity investor base.Going beyond metro citiesInvestment activity is increasingly coming from smaller cities. Around 55–60% of new SIP registrations now originate from B30 cities, highlighting the growing role of Tier-2 and Tier-3 regions in driving mutual fund growth.Rising financial literacy and awarenessThe spread of regional and digital financial content across YouTube, Instagram and fintech platforms has made investing concepts more accessible. Regulatory awareness campaigns by AMFI — including “Mutual Funds Sahi Hai” and “Bharat Nivesh Yatra” — have further boosted investor education.Market performance reinforcing trustSustained returns have strengthened long-term investor confidence. The Nifty 50 and Sensex delivered 10–15% returns over the last decade, while equity-oriented mutual funds have significantly outperformed traditional fixed deposits over the past five years.

Women and GenZ hit investment markets

GenZYounger investors are emerging as key drivers of the shift from traditional savings to investment. Data from the NSE shows that more than half, almost 56%, of newly registered investors are below 30. Mutual fund trends also reflected this shift, with 55% of investors under 40 and the 20–30 age group emerging as the fastest-growing segment in the top 100 cities.Comparing the contribution of GenZ and millennials, Rohit Shah said that according to the data, both cohorts contribute meaningfully, but with distinct patterns.“GenZ dominates app-based trading volumes due to digital nativity and lower capital requirements. Millennials drive mutual fund and long-term investments through larger disposable incomes and established goals.” He further added, after the market expansion happening after the pandemic, benefited both simultaneously, “making it difficult to isolate one generation as the primary driver. The real story lies in democratization across age groups, not generational dominance.The equity shift is broad-based across age groups according to AMFI’s age-wise distribution of individual investor AUM. Gen Z investors (under 25 years) have allocated nearly 65% of their assets to equity, Rajani told TOI. Millennials (25–44 years), meanwhile, “show the highest equity allocation at approximately 75.5%, and importantly, even investors above 58 years of age maintain a meaningful equity allocation of around 54%”Nirav Karkera, head of research at Fisdom, highlighted a different approach, saying that while millennials currently lead the equity surge, the baton is likely to pass to Gen Z in the coming years. “Gen Z is still in the early stage of their earning life, where consumption tends to dominate. At the same time, they are arguably the most financially aware generation we have seen. They understand the language of money much earlier than millennials did at their age. Once their incomes rise and they have surplus capital, they are likely to play an even bigger role than millennials in shaping investment patterns. For now, millennials are doing the heavy lifting, but the baton looks set to pass smoothly to Gen Z.”WomenAs of November 2025, women account for nearly a quarter of India’s investor base, highlighting their growing presence in financial markets. Data from NSE shows that over the corresponding period, women’s share in the individual investor base has remained stable at 24.7% over the corresponding period. Among the top five states by registered investors, Maharashtra leads with women comprising 28.8% of its investor pool, up from 25.6% in FY23, followed closely by Gujarat at 28.1% (26.6% in FY23). In contrast, Uttar Pradesh, despite being the second-largest state by investor count, continues to lag, with women forming 18.9% of investors, though this marks an improvement from 16.9% in FY23.Encouragingly, nearly 53% of Indian states now report female investor participation above the national average, compared to 44% in FY23. Smaller regions are emerging as frontrunners in gender inclusion, with Goa (33.1%), Mizoram (32.4%), Chandigarh (32.2%), Sikkim (31.1%) and Delhi (30.9%) leading the way – reflecting rising financial awareness, greater workforce participation, and improved access to investment avenues among women. Mutual funds also saw rising participation from women, particularly in B30 cities, where the share of women investors climbed from 20% to 25% over the past five years. In the top 30 cities, women now make up nearly 35% of mutual fund investors as of FY25, accompanied by a sharper rise in average MF folio sizes between FY19 and FY24.

Short-term or long-term: Where are Indians putting their money?

Indian investors are participating across both short-term trading and long-term wealth building, but experts say the balance is slowly tilting toward the latter. In the immediate post-Covid phase, many first-time investors entered markets with speculative intent. However, that period helped break psychological barriers. “Once investors experienced volatility firsthand rather than hearing about it abstractly, they started building familiarity, confidence and a basic understanding of market behaviour,” said Karkera, adding that the early rush acted as a gateway to more mature participation.Rajani told TOI that the trend is driven by long term objectives rather than short term. The expert pointed to AMFI’s SIP holding-period analysis, which shows that the share of SIP assets held for over five years has jumped from 11% to 29% in the past five years, while investments held for less than a year have fallen sharply from 41% to 23%.Meanwhile Shah said that even though “retail trading volumes have grown exponentially—NSE data shows consistent month-on-month increases in F&O participation. Simultaneously, mutual fund SIP adoption remains strong, but it’s overshadowed by trading activity. With fixed deposit yields compressed by falling interest rates, investors are chasing equity returns without corresponding time horizons. The evidence suggests a bifurcation: disciplined SIP investors versus growing trading populations driven by short-term performance metrics.”

Are there any risks for the investment express?

Shah warned that many new investors entered the market during a long bull run, and historically, market corrections of 30–50% happen every 7–10 years. Therefore, a prolonged downturn could lead to panic selling, especially among first-time investors with little experience of market volatility. Meanwhile, in the short term, market ups and downs may push some investors to move money into safer options like debt funds. Investors also tend to chase assets that have done well recently, such as gold and silver. However, Rajani pointed out that these shifts are temporary and not a fundamental change. “Over the long term, the broader trend toward equity investing is expected to continue as investors looking for inflation-beating returns to meet long-term financial goals.”Karkera also highlighted that even though risks remain, they are manageable. He noted that lower equity returns or bouts of market volatility could cause short-term, speculative investors to step back, and better performance in fixed-income or real assets may temporarily pull some money away from equities. However, the larger shift is firmly in place thanks to improved investor awareness, growing digital access. “Growth may pause or plateau intermittently, but the long-term trajectory of retail participation still feels upward.”

Still room to grow

Despite the rapid shift, India continues to lag developed markets. Mutual funds and equities account for just 15–20% of household investable assets, compared with 50–60% in countries like the US and Canada, highlighting significant headroom for future growth.As the Bain report notes: Over the next decade, mutual fund AUM is projected to cross Rs 300 lakh crore, while direct equity holdings could approach Rs 250 lakh crore, supported by deeper penetration in tier-2 and tier-3 cities, regulatory reforms and investor education initiatives.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoUK says provided assistance in US-led tanker seizure

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoDoes new US food pyramid put too much steak on your plate?

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoWhy did Nick Reiner’s lawyer Alan Jackson withdraw from case?

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoClock is ticking for Frank at Spurs, with dwindling evidence he deserves extra time

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoTrump moves to ban home purchases by institutional investors

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoPGA of America CEO steps down after one year to take care of mother and mother-in-law

-

Tech4 days ago

Tech4 days agoNew Proposed Legislation Would Let Self-Driving Cars Operate in New York State

-

Sports7 days ago

Commanders go young, promote David Blough to be offensive coordinator