Tech

Engineers design origami structures that change shape and stiffness on demand

Princeton engineers are twisting, stretching and creasing structures to create a new type of origami, one that changes its shape and properties in response to changing circumstances. The new method could be useful for prosthetics, antennas and other devices.

When a device needs to fit into a compact space—in a spacecraft or a surgical device—and then unfold into an intricate shape, origami often provides a solution. But most origami shapes are locked into a few set patterns once their folds are made.

A Princeton team led by Glaucio Paulino wanted to create structures that react to an outside stimulus in multiple ways, not just in a few patterned responses. To accomplish this, the team turned to a technique called geometric frustration.

An origami-based structure will fold and twist in certain ways based on the structure’s material properties and its geometry. When engineers prevent that natural motion, they call it “frustrating” the structure. Normally, engineers have to work around frustration, but in this case it expands their toolkit.

“Sometimes frustration is desirable,” said Paulino, the Margareta Engman Augustine Professor of Engineering at Princeton. Frustration allows designers to cause the origami to follow patterns not normally allowed by its geometry. “This opens up many possibilities of things we could engineer that we could never do before.”

In an article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers described how they added elastic components to cylindrical origami structures called Kresling cells. The elastic sections act like springs. By controlling how the springs respond to a force, the researchers were able to execute precise folding patterns of the cells that were not feasible without the springs.

Paulino said springs allow designers to introduce internal energy into the folded structure using pre-stress. This pre-stress allows the origami to respond in ways that are not possible with ordinary materials. For example, engineers can introduce a twisting spring that rotates the origami in a specific fashion; they can add a spring along the structure’s main axis that either squeezes the structure into a compact shape or stretches it out.

By combining frustrated cells in stacks, the engineers were able to develop materials with fine control over material properties like stiffness. For example, a prosthetic leg built with this system can stiffen to provide support while walking on a flat surface but reconfigure into a more flexible state for climbing stairs. The designers could also create adjustable metasurfaces that are used in antennas and optics.

“Exploiting frustration lets us reprogram origami mechanics, for instance turning random Kresling folding into precise, controllable sequences and opening new possibilities for advanced applications,” said Diego Misseroni, a collaborator from the University of Trento.

“We can program any mechanical property that we wish, so this is quite unique,” said Tuo Zhao, a postdoctoral researcher in Paulino’s group.

The team sees potential impact for this type of structure in many fields. This frustrated origami system can combine with other techniques and materials that can change on demand, according to Shixi Zang, postdoctoral researcher and first author of the paper. One example is using frustrated origami to develop responsive, modular devices like a passive sunshade that opens and closes based on the ambient temperature.

More information:

Shixi Zang et al, Origami frustration and its influence on energy landscapes of origami assemblies, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2426790122

Citation:

Engineers design origami structures that change shape and stiffness on demand (2025, September 6)

retrieved 6 September 2025

from https://techxplore.com/news/2025-09-origami-stiffness-demand.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

Tech

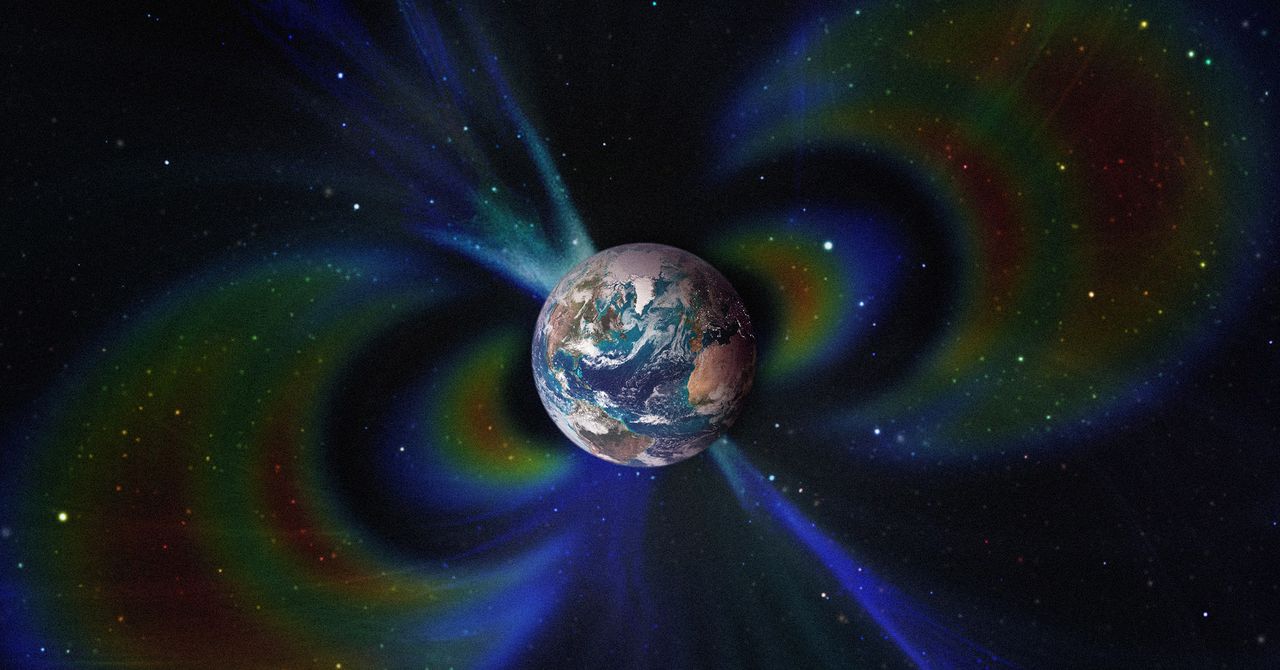

Two Titanic Structures Hidden Deep Within the Earth Have Altered the Magnetic Field for Millions of Years

A team of geologists has found for the first time evidence that two ancient, continent-sized, ultrahot structures hidden beneath the Earth have shaped the planet’s magnetic field for the past 265 million years.

These two masses, known as large low-shear-velocity provinces (LLSVPs), are part of the catalog of the planet’s most enormous and enigmatic objects. Current estimates calculate that each one is comparable in size to the African continent, although they remain buried at a depth of 2,900 kilometers.

Low-lying surface vertical velocity (LLVV) regions form irregular areas of the Earth’s mantle, not defined blocks of rock or metal as one might imagine. Within them, the mantle material is hotter, denser, and chemically different from the surrounding material. They are also notable because a “ring” of cooler material surrounds them, where seismic waves travel faster.

Geologists had suspected these anomalies existed since the late 1970s and were able to confirm them two decades later. After another 10 years of research, they now point to them directly as structures capable of modifying Earth’s magnetic field.

LLSVPs Alter the Behavior of the Nucleus

According to a study published this week in Nature Geoscience and led by researchers at the University of Liverpool, temperature differences between LLSVPs and the surrounding mantle material alter the way liquid iron flows in the core. This movement of iron is responsible for generating Earth’s magnetic field.

Taken together, the cold and ultrahot zones of the mantle accelerate or slow the flow of liquid iron depending on the region, creating an asymmetry. This inequality contributes to the magnetic field taking on the irregular shape we observe today.

The team analyzed the available mantle evidence and ran simulations on supercomputers. They compared how the magnetic field should look if the mantle were uniform versus how it behaves when it includes these heterogeneous regions with structures. They then contrasted both scenarios with real magnetic field data. Only the model that incorporated the LLSVPs reproduced the same irregularities, tilts, and patterns that are currently observed.

The geodynamo simulations also revealed that some parts of the magnetic field have remained relatively stable for hundreds of millions of years, while others have changed remarkably.

“These findings also have important implications for questions surrounding ancient continental configurations—such as the formation and breakup of Pangaea—and may help resolve long-standing uncertainties in ancient climate, paleobiology, and the formation of natural resources,” said Andy Biggin, first author of the study and professor of Geomagnetism at the University of Liverpool, in a press release.

“These areas have assumed that Earth’s magnetic field, when averaged over long periods, behaved as a perfect bar magnet aligned with the planet’s rotational axis. Our findings are that this may not quite be true,” he added.

This story originally appeared in WIRED en Español and has been translated from Spanish.

Tech

Loyalty Is Dead in Silicon Valley

Since the middle of last year, there have been at least three major AI “acqui-hires” in Silicon Valley. Meta invested more than $14 billion in Scale AI and brought on its CEO, Alexandr Wang; Google spent a cool $2.4 billion to license Windsurf’s technology and fold its cofounders and research teams into DeepMind; and Nvidia wagered $20 billion on Groq’s inference technology and hired its CEO and other staffers.

The frontier AI labs, meanwhile, have been playing a high stakes and seemingly never-ending game of talent musical chairs. The latest reshuffle began three weeks ago, when OpenAI announced it was rehiring several researchers who had departed less than two years earlier to join Mira Murati’s startup, Thinking Machines. At the same time, Anthropic, which was itself founded by former OpenAI staffers, has been poaching talent from the ChatGPT maker. OpenAI, in turn, just hired a former Anthropic safety researcher to be its “head of preparedness.”

The hiring churn happening in Silicon Valley represents the “great unbundling” of the tech startup, as Dave Munichiello, an investor at GV, put it. In earlier eras, tech founders and their first employees often stayed onboard until either the lights went out or there was a major liquidity event. But in today’s market, where generative AI startups are growing rapidly, equipped with plenty of capital, and prized especially for the strength of their research talent, “you invest in a startup knowing it could be broken up,” Munichiello told me.

Early founders and researchers at the buzziest AI startups are bouncing around to different companies for a range of reasons. A big incentive for many, of course, is money. Last year Meta was reportedly offering top AI researchers compensation packages in the tens or hundreds of millions of dollars, offering them not just access to cutting-edge computing resources but also … generational wealth.

But it’s not all about getting rich. Broader cultural shifts that rocked the tech industry in recent years have made some workers worried about committing to one company or institution for too long, says Sayash Kapoor, a computer science researcher at Princeton University and a senior fellow at Mozilla. Employers used to safely assume that workers would stay at least until the four-year mark when their stock options were typically scheduled to vest. In the high-minded era of the 2000s and 2010s, plenty of early cofounders and employees also sincerely believed in the stated missions of their companies and wanted to be there to help achieve them.

Now, Kapoor says, “people understand the limitations of the institutions they’re working in, and founders are more pragmatic.” The founders of Windsurf, for example, may have calculated their impact could be larger at a place like Google that has lots of resources, Kapoor says. He adds that a similar shift is happening within academia. Over the past five years, Kapoor says, he’s seen more PhD researchers leave their computer-science doctoral programs to take jobs in industry. There are higher opportunity costs associated with staying in one place at a time when AI innovation is rapidly accelerating, he says.

Investors, wary of becoming collateral damage in the AI talent wars, are taking steps to protect themselves. Max Gazor, the founder of Striker Venture Partners, says his team is vetting founding teams “for chemistry and cohesion more than ever.” Gazor says it’s also increasingly common for deals to include “protective provisions that require board consent for material IP licensing or similar scenarios.”

Gazor notes that some of the biggest acqui-hire deals that have happened recently involved startups founded long before the current generative AI boom. Scale AI, for example, was founded in 2016, a time when the kind of deal Wang negotiated with Meta would have been unfathomable to many. Now, however, these potential outcomes might be considered in early term sheets and “constructively managed,” Gazor explains.

Tech

ICE and CBP’s Face-Recognition App Can’t Actually Verify Who People Are

The face-recognition app Mobile Fortify, now used by United States immigration agents in towns and cities across the US, is not designed to reliably identify people in the streets and was deployed without the scrutiny that has historically governed the rollout of technologies that impact people’s privacy, according to records reviewed by WIRED.

The Department of Homeland Security launched Mobile Fortify in the spring of 2025 to “determine or verify” the identities of individuals stopped or detained by DHS officers during federal operations, records show. DHS explicitly linked the rollout to an executive order, signed by President Donald Trump on his first day in office, which called for a “total and efficient” crackdown on undocumented immigrants through the use of expedited removals, expanded detention, and funding pressure on states, among other tactics.

Despite DHS repeatedly framing Mobile Fortify as a tool for identifying people through facial recognition, however, the app does not actually “verify” the identities of people stopped by federal immigration agents—a well-known limitation of the technology and a function of how Mobile Fortify is designed and used.

“Every manufacturer of this technology, every police department with a policy makes very clear that face recognition technology is not capable of providing a positive identification, that it makes mistakes, and that it’s only for generating leads,” says Nathan Wessler, deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project.

Records reviewed by WIRED also show that DHS’s hasty approval of Fortify last May was enabled by dismantling centralized privacy reviews and quietly removing department-wide limits on facial recognition—changes overseen by a former Heritage Foundation lawyer and Project 2025 contributor, who now serves in a senior DHS privacy role.

DHS—which has declined to detail the methods and tools that agents are using, despite repeated calls from oversight officials and nonprofit privacy watchdogs—has used Mobile Fortify to scan the faces not only of “targeted individuals,” but also people later confirmed to be US citizens and others who were observing or protesting enforcement activity.

Reporting has documented federal agents telling citizens they were being recorded with facial recognition and that their faces would be added to a database without consent. Other accounts describe agents treating accent, perceived ethnicity, or skin color as a basis to escalate encounters—then using face scanning as the next step once a stop is underway. Together, the cases illustrate a broader shift in DHS enforcement toward low-level street encounters followed by biometric capture like face scans, with limited transparency around the tool’s operation and use.

Fortify’s technology mobilizes facial capture hundreds of miles from the US border, allowing DHS to generate nonconsensual face prints of people who, “it is conceivable,” DHS’s Privacy Office says, are “US citizens or lawful permanent residents.” As with the circumstances surrounding its deployment to agents with Customs and Border Protection and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Fortify’s functionality is visible mainly today through court filings and sworn agent testimony.

In a federal lawsuit this month, attorneys for the State of Illinois and the City of Chicago said the app had been used “in the field over 100,000 times” since launch.

In Oregon testimony last year, an agent said two photos of a woman in custody taken with his face-recognition app produced different identities. The woman was handcuffed and looking downward, the agent said, prompting him to physically reposition her to obtain the first image. The movement, he testified, caused her to yelp in pain. The app returned a name and photo of a woman named Maria; a match that the agent rated “a maybe.”

Agents called out the name, “Maria, Maria,” to gauge her reaction. When she failed to respond, they took another photo. The agent testified the second result was “possible,” but added, “I don’t know.” Asked what supported probable cause, the agent cited the woman speaking Spanish, her presence with others who appeared to be noncitizens, and a “possible match” via facial recognition. The agent testified that the app did not indicate how confident the system was in a match. “It’s just an image, your honor. You have to look at the eyes and the nose and the mouth and the lips.”

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoPSX witnesses 6,000-point on Middle East tensions | The Express Tribune

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoThe Surface Laptop Is $400 Off

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoHere’s the Company That Sold DHS ICE’s Notorious Face Recognition App

-

Tech4 days ago

Tech4 days agoHow to Watch the 2026 Winter Olympics

-

Tech6 days ago

Tech6 days agoRight-Wing Gun Enthusiasts and Extremists Are Working Overtime to Justify Alex Pretti’s Killing

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoBudget 2026: Defence, critical minerals and infra may get major boost

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoPeyton List talks new season of "School Spirits" and performing in off-Broadway hit musical

-

Fashion7 days ago

Fashion7 days agoItaly’s Brunello Cucinelli debuts Callimacus AI e-commerce experience