Tech

Trump Imposes New Tariffs to Sidestep Supreme Court Ruling

President Trump is adding a new 10 percent tariff on nearly all imports to the United States, following a Supreme Court ruling that overturned most of the levies imposed by the US government last year.

In an executive order signed Friday evening, Trump outlined a few exceptions, including imports of critical minerals, beef and fruits, cars, pharmaceuticals, and products from Canada or Mexico. The new tariffs will take effect on February 24, 2026.

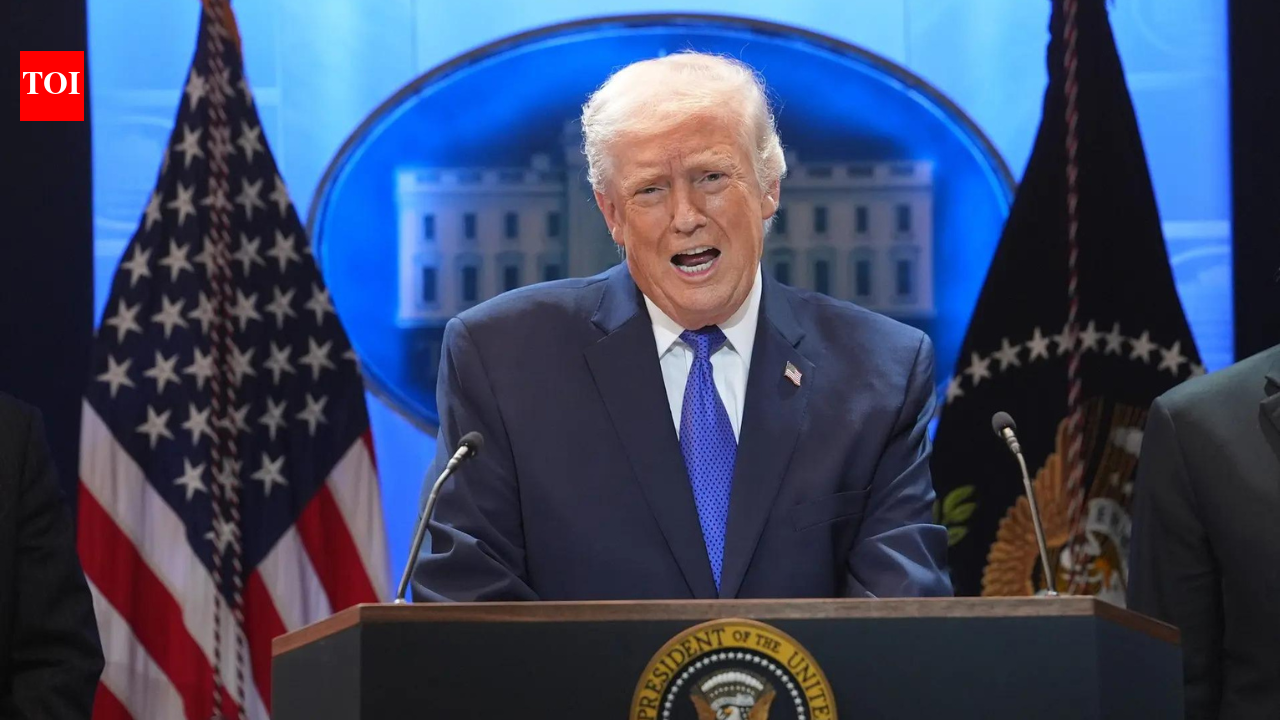

In a press conference Friday afternoon, Trump was fired up about the Supreme Court decision and resorted to personal attacks, calling the six justices who ruled against his trade policies “a disgrace to our nation.” Answering a reporter’s question about how two of the justices he nominated, Neil Gorsuch and Amy Coney Barrett, voted for the overturn, Trump called them “an embarrassment to their families.”

The new trade policy is based on Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974, which allows the president to single-handedly and immediately charge tariffs of up to 15 percent if there are “large and serious” trade deficits. These tariffs only last 150 days unless Congress authorizes an extension. Like the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), the statute has never before been used by a US president in this way.

Once the 150-day deadline arrives, it’s possible for Trump to keep re-issuing Section 122 tariffs. But the administration could also use this time to prepare other forms of tariffs, essentially switching legal justifications to get the same regulatory effects, says Gregory Husisian, a partner and litigation attorney at Foley & Lardner LLP, which has helped over one hundred companies file requests for tariff refunds. “[Section 122 tariff] is for a limited time period, so it’s going to be a bridge authority,” Husisian says.

In the meantime, the Trump administration could rush through the process of conducting trade investigations based on concerns of national security or unfair trade practices abroad, which are a requirement for launching Section 301 and Section 232 tariffs. “We are also initiating several Section 301 and other investigations to protect our country from unfair trade practices of other countries and companies,” Trump said at the press conference, referring to these other tariff options that take longer to launch.

In a separate executive order, the administration confirmed that despite IEEPA tariffs being overturned, the de minimis exemption—which is used to exempt e-commerce packages under $800 in value from being taxed—remains suspended. The end of de minimis last year caused massive package processing backlogs at the US border as well as price increases on budget shopping platforms.

At the press conference, Trump didn’t specify what exactly would happen to companies seeking refunds on their tariff payments. The Supreme Court decision did not specify whether and how the tariffs should be refunded. Answering a reporter’s question on the topic, Trump said he expected the issue to be litigated in court.

Experts tell WIRED that they expect the refund process to be messy and long, since it might require companies to file complaints and calculate the amount of money they believe they are entitled to receive. The government could also then push back on the calculated amount. The process could last anywhere from a few months to more than two years.

The Supreme Court decision specified that the IEEPA gives the president significant power during emergencies, but noted this power doesn’t extend to taxation. Trump, at the press conference, repeatedly distorted the ruling: “But now the court has given me the unquestioned right to ban all sorts of things from coming into our country, to destroy foreign countries … but not the right to charge a fee,” he said. “How crazy is that?”

At times, the press conference turned into a rant about issues unrelated to tariffs, like how the president thinks Europe is too woke or how much he hates the Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell. Speaking about how the court interprets the literal meaning of the IEEPA, Trump suddenly started bragging about his reading comprehension skills. “I read the paragraphs. I read very well. Great comprehension,” he said.

Tech

The Supreme Court’s Tariff Ruling Won’t Bring Car Prices Back to Earth

It has never been more expensive to buy a new car. The average transaction price last month for buyers in the United States was $48,576, up nearly a third from 2019, according to Edmunds. The “affordable” car—$20,000 or less—is dead.

The high prices have been pinned on plenty of economic dynamics: lingering pandemic-era supply chain issues, the introduction of expensive technology into everyday cars, higher labor and raw materials costs, and new tariffs by the Trump administration affecting imported steel, aluminum, and cars themselves.

Now, despite a US Supreme Court ruling that will nix some of those Trump tariffs, car buyers will likely get no respite.

“The core cost structure facing the auto industry hasn’t fundamentally changed overnight,” writes Jessica Caldwell, Edmunds’ head of insights, in an emailed statement. Put more simply: Cheaper cars aren’t coming, at least not because of this ruling.

The Supreme Court’s decision gets in the way of the president’s power to use the International Emergency Economic Power Act, or IEEPA, to levy tariffs in response to emergencies. Trump used this power to apply tariffs to countries around the globe, the emergency being “large and persistent” trade deficits. The administration applied other new duties on Canada, China, and Mexico because of what it called emergencies related to the flow of migrants and drugs into the United States.

But most of the tariffs that affect the auto industry come from another law, section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act. That provision can apply to imports that “threaten to impair” the country’s national security. Tariffs on steel, aluminum, copper—key raw materials for cars—and imported auto parts and vehicles themselves came under this provision, and are still in effect. This includes 15 percent tariffs on cars built in Europe, Japan, and South Korea.

Automakers have actually done an OK job shielding consumers from the effects of tariffs, Caldwell says. Even as retailers have blamed tariffs for steadily rising prices of consumer goods like electronics and appliances, car prices are up just 1 percent since this time last year, the firm’s data shows. But as the tariff regime drags on, that could change in ways that make new car buyers even less happy.

“If cost pressures continue to build, automakers may have less room to shield shoppers from higher prices,” Caldwell says, “but for now, the broader market impact is still playing out.”

Tech

Government Docs Reveal New Details About Tesla and Waymo Robotaxis’ Human Babysitters

Are self-driving vehicles really just big, remote-controlled cars, with nameless and faceless people in far-off call centers piloting the things from behind consoles? As the vehicles and their science-fiction-like software expand to more cities, the conspiracy theory has rocketed around group chats and TikToks. It’s been powered, in part, by the reluctance of self-driving car companies to talk in specifics about the humans who help make their robots go.

But this month, in government documents submitted by Alphabet subsidiary Waymo and electric-auto maker Tesla, the companies have revealed more details about the people and programs that help the vehicles when their software gets confused.

The details of these companies’ “remote assistance” programs are important because the humans supporting the robots are critical in ensuring the cars are driving safely on public roads, industry experts say. Even robotaxis that run smoothly most of the time get into situations that their self-driving systems find perplexing. See, for example, a December power outage in San Francisco that killed stop lights around the city, stranding confused Waymos in several intersections. Or the ongoing government probes into several instances of these cars illegally blowing past stopped school buses unloading students in Austin, Texas. (The latter led Waymo to issue a software recall.) When this happens, humans get the cars out of the jam by directing or “advising” them from afar.

These jobs are important because if people do them wrong, they can be the difference between, say, a car stopping for or running a red light. “For the foreseeable future, there will be people who play a role in the vehicles’ behavior, and therefore have a safety role to play,” says Philip Koopman, an autonomous-vehicle software and safety researcher at Carnegie Mellon University. One of the hardest safety problems associated with self-driving, he says, is building software that knows when to ask for human help.

In other words: If you care about robot safety, pay attention to the people.

The People of Waymo

Waymo operates a paid robotaxi service in six metros—Atlanta, Austin, Los Angeles, Phoenix, and the San Francisco Bay Area—and has plans to launch in at least 10 more, including London, this year. Now, in a blog post and letter submitted to US senator Ed Markey this week, the company made public more aspects of what it calls its “remote assistance” (RA) program, which uses remote workers to respond to requests from Waymo’s vehicle software when it determines it needs help. These humans give data or advice to the systems, writes Ryan McNamara, Waymo’s vice president and global head of operations. The system can use or reject the information that humans provide.

“Waymo’s RA agents provide advice and support to the Waymo Driver but do not directly control, steer, or drive the vehicle,” McNamara writes—denying, implicitly, the charge that Waymos are simply remote-controlled cars. About 70 assistants are on duty at any given time to monitor some 3,000 robotaxis, the company says. The low ratio indicates the cars are doing much of the heavy lifting.

Waymo also confirmed in its letter what an executive told Congress in a hearing earlier this month: Half of these remote assistance workers are contractors overseas, in the Philippines. (The company says it has two other remote assistance offices in Arizona and Michigan.) These workers are licensed to drive in the Philippines, McNamara writes, but are trained on US road rules. All remote assistance workers are drug- and alcohol-tested when they are hired, the company says, and 45 percent are drug-tested every three months as part of Waymo’s random testing program.

Tech

DHS Wants a Single Search Engine to Flag Faces and Fingerprints Across Agencies

The Department of Homeland Security is moving to consolidate its face recognition and other biometric technologies into a single system capable of comparing faces, fingerprints, iris scans, and other identifiers collected across its enforcement agencies, according to records reviewed by WIRED.

The agency is asking private biometric contractors how to build a unified platform that would let employees search faces and fingerprints across large government databases already filled with biometrics gathered in different contexts. The goal is to connect components including Customs and Border Protection, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Transportation Security Administration, US Citizenship and Immigration Services, the Secret Service, and DHS headquarters, replacing a patchwork of tools that do not share data easily.

The system would support watchlisting, detention, or removal operations and comes as DHS is pushing biometric surveillance far beyond ports of entry and into the hands of intelligence units and masked agents operating hundreds of miles from the border.

The records show DHS is trying to buy a single “matching engine” that can take different kinds of biometrics—faces, fingerprints, iris scans, and more—and run them through the same backend, giving multiple DHS agencies one shared system. In theory, that means the platform would handle both identity checks and investigative searches.

For face recognition specifically, identity verification means the system compares one photo to a single stored record and returns a yes-or-no answer based on similarity. For investigations, it searches a large database and returns a ranked list of the closest-looking faces for a human to review instead of independently making a call.

Both types of searches come with real technical limits. In identity checks, the systems are more sensitive, and so they are less likely to wrongly flag an innocent person. They will, however, fail to identify a match when the photo submitted is slightly blurry, angled, or outdated. For investigative searches, the cutoff is considerably lower, and while the system is more likely to include the right person somewhere in the results, it also produces many more false positives that necessitate human review.

The documents make clear that DHS wants control over how strict or permissive a match should be—depending on the context.

The department also wants the system wired directly into its existing infrastructure. Contractors would be expected to connect the matcher to current biometric sensors, enrollment systems, and data repositories so information collected in one DHS component can be searched against records held by another.

It’s unclear how workable this is. Different DHS agencies have bought their biometric systems from different companies over many years. Each system turns a face or fingerprint into a string of numbers, but many are designed only to work with the specific software that created them.

In practice, this means a new department-wide search tool cannot simply “flip a switch” and make everything compatible. DHS would likely have to convert old records into a common format, rebuild them using a new algorithm, or create software bridges that translate between systems. All of these approaches take time and money, and each can affect speed and accuracy.

At the scale DHS is proposing—potentially billions of records—even small compatibility gaps can spiral into large problems.

The documents also contain a placeholder indicating DHS wants to incorporate voiceprint analysis, but it contains no detailed plans for how they would be collected, stored, or searched. The agency previously used voiceprints in its “Alternative to Detention” program, which allowed immigrants to remain in their communities but required them to submit to intensive monitoring, including GPS ankle trackers and routine check-ins that confirmed their identity using biometric voiceprints.

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoTop stocks to buy today: Stock recommendations for February 13, 2026 – check list – The Times of India

-

Fashion1 week ago

Fashion1 week agoIndia’s PDS Q3 revenue up 2% as margins remain under pressure

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoIndia clears proposal to buy French Rafale jets

-

Fashion1 week ago

Fashion1 week ago$10→ $12.10 FOB: The real price of zero-duty apparel

-

Tech1 week ago

Tech1 week agoElon Musk’s X Appears to Be Violating US Sanctions by Selling Premium Accounts to Iranian Leaders

-

Tech4 days ago

Tech4 days agoRakuten Mobile proposal selected for Jaxa space strategy | Computer Weekly

-

Entertainment4 days ago

Entertainment4 days agoQueen Camilla reveals her sister’s connection to Princess Diana

-

Entertainment4 days ago

Entertainment4 days agoRobert Duvall, known for his roles in "The Godfather" and "Apocalypse Now," dies at 95