Tech

What to Look for When Buying a Sleep Mask: Do They Really Help? What Type Is Best?

When it’s time to wind down, even a thin beam of streetlight coming through the curtains or the glow of a phone charger can keep your brain from fully switching off. A well-made sleep mask that blocks the light can help you drift off faster and stay asleep even through sunrise.

So forget those flimsy airline eye covers. Sleep masks have come a long way, and the market is filled with a myriad of options designed to help you fall asleep and maintain a good night’s rest. From luxurious silk masks to high-tech sleeping goggles, there’s a sleep mask for every need. Below, we break down what to look for in a sleep mask, the benefits each type offers, and how to get the most out of one so you can sleep like you mean it.

Don’t know where to start when it comes to purchasing a sleep mask for your needs? We’re here to break down all the things you should consider.

For better sleep all around, check out our guide to the Best Sleep Masks, as well as other sleep-related guides, including Best Mattresses, Best Sheets, Best Pillows, and Best Organic Mattresses.

Jump to Section

Sleep Mask Benefits

Sleep masks do more than just block out light. Whether you’re jet-lagged, catching up after a night shift, or simply looking to improve your nightly routine, the benefits of a sleep mask can be long-lasting after a good night’s rest.

Light is the most powerful cue for your circadian rhythm. It essentially tells your brain what time it is. Even the tiniest bit of light exposure can suppress melatonin and delay sleep.

“Most research has been conducted in hospitals due to the noise and lights,” says sleep physician Lourdes DelRosso. “Providing sleep masks and earplugs to hospitalized patients has been studied and published, showing that patients experience deeper and more restful sleep. Just by covering their eyes, we can promote better production of melatonin and send better signals to our brain.” Wearing sleep masks at night can also aid cognitive function, including memory, alertness, and episodic learning, according to a study from the Sleep Research Society.

Wearing sleep masks at night can also aid cognitive function, including memory, alertness, and episodic learning, according to a study from the Sleep Research Society.

And it’s not just the blackout effect of sleep masks that gives users a well-rested night. Sleep masks are a healthy sleep association, providing a relaxing and comforting experience that can help you wind down at night.

“We have touch receptors everywhere on our skin, including around the eyes,” certified sleep expert Annika Carroll says. “If we apply a little bit of light pressure there with this mask, it releases a hormone called oxytocin, often referred to as the love hormone. It promotes relaxation and comfort.”

If you’re prone to migraines, eye masks can be a simple and powerful ally. Light pressure around the eyes can help ease tension and increase blood flow, while total darkness helps reduce light sensitivity, a common migraine trigger.

Friction breaks down the skin’s elastin and collagen, the proteins that keep your face firm and smooth. Wearing an eye mask while you sleep protects the delicate skin around your eyes from rubbing against bedding or your arm, especially if you tend to toss and turn.

We all know the signs of a rough night of sleep: puffy eyes and dark circles. A sleep mask can help tip the odds by boosting circulation in your face, and weighted eye masks can help break up the excess fluid around the eyes that leads to puffiness.

What Shape and Fit Should I Consider?

Sleep mask fits aren’t universal, Carroll says: “I find that there’s a bit of trial and error in finding a mask that fits your face shape. There are rounder faces, and there are slimmer, longer faces.” Be sure to try on a new sleep mask before giving it a whirl; the mask should press gently against your face without feeling too tight, and there should be no gaps between the mask and your skin, especially around the nose. Additionally, several sleep mask characteristics may affect how well it fits on your face.

Flat sleep masks are the most traditional type you’ll see—a flat piece of fabric that covers the eyes. These types are generally lighter and more compact, making them easy to travel with. Comfort may be a factor here, since flat masks tend to press against the eyes, which some may find bothersome.

A common problem with traditional slip-on sleep masks is the bridge of the nose lifting the mask, allowing light to seep in and defeating the purpose of wearing it. Many sleep masks today are designed with a contoured nose or without fabric around the nose to prevent any light from penetrating.

Some eye masks are built like swim goggles: They feature two convex gaps that allow you to fully open and close your eyes beneath the mask without letting any light in. Eye cups are especially beneficial for people with sensitive eyes and for people who wear eyelash extensions.

Too loose, and the mask will fall off throughout the night. Too tight, and it could uncomfortably press against your eyes or snag your hair while you’re sleeping. Luckily, many sleep masks come with an adjustable strap so you can customize the fit.

When shopping for a sleep mask, examine the product to locate any clasps or adjustable closures. If you’re a back sleeper, you might prefer this piece on the side of your head. Stomach sleepers may find a clasp at the back more comfortable. For those who change positions frequently, consider an unobtrusive adjustment and/or closure mechanism like slim Velcro, a magnetic closure, or a slide buckle.

Tech

Asus Made a Split Keyboard for Gamers—and Spared No Expense

The wheel on the left side has options to adjust actuation distance, rapid-trigger sensitivity, and RGB brightness. You can also adjust volume and media playback, and turn it into a scroll wheel. The LED matrix below it is designed to display adjustments to actuation distance but feels a bit awkward: Each 0.1 mm of adjustment fills its own bar, and it only uses the bottom nine bars, so the screen will roll over four times when adjusting (the top three bars, with dots next to them, illuminate to show how many times the screen has rolled over during the adjustment). The saving grace of this is that, when adjusting the actuation distance, you can press down any switch to see a visualization of how far you’re pressing it, then tweak the actuation distance to match.

Alongside all of this, the Falcata (and, by extension, the Falchion) now has an aftermarket switch option: TTC Gold magnetic switches. While this is still only two switches, it’s an improvement over the singular switch option of most Hall effect keyboards.

Split Apart

Photograph: Henri Robbins

The internal assembly of this keyboard is straightforward yet interesting. Instead of a standard tray mount, where the PCB and plate bolt directly into the bottom half of the shell, the Falcata is more comparable to a bottom-mount. The PCB screws into the plate from underneath, and the plate is screwed onto the bottom half of the case along the edges. While the difference between the two mounting methods is minimal, it does improve typing experience by eliminating the “dead zones” caused by a post in the middle of the keyboard, along with slightly isolating typing from the case (which creates fewer vibrations when typing).

The top and bottom halves can easily be split apart by removing the screws on the plate (no breakable plastic clips here!), but on the left half, four cables connect the top and bottom halves of the keyboard, all of which need to be disconnected before fully separating the two sections. Once this is done, the internal silicone sound-dampening can easily be removed. The foam dampening, however, was adhered strongly enough that removing it left chunks of foam stuck to the PCB, making it impossible to readhere without using new adhesive. This wasn’t a huge issue, since the foam could simply be placed into the keyboard, but it is still frustrating to see when most manufacturers have figured this out.

Tech

These Sub-$300 Hearing Aids From Lizn Have a Painful Fit

Don’t call them hearing aids. They’re hearpieces, intended as a blurring of the lines between hearing aid and earbuds—or “earpieces” in the parlance of Lizn, a Danish operation.

The company was founded in 2015, and it haltingly developed its launch product through the 2010s, only to scrap it in 2020 when, according to Lizn’s history page, the hearing aid/earbud combo idea didn’t work out. But the company is seemingly nothing if not persistent, and four years later, a new Lizn was born. The revamped Hearpieces finally made it to US shores in the last couple of weeks.

Half Domes

Photograph: Chris Null

Lizn Hearpieces are the company’s only product, and their inspiration from the pro audio world is instantly palpable. Out of the box, these look nothing like any other hearing aids on the market, with a bulbous design that, while self-contained within the ear, is far from unobtrusive—particularly if you opt for the graphite or ruby red color scheme. (I received the relatively innocuous sand-hued devices.)

At 4.58 grams per bud, they’re as heavy as they look; within the in-the-ear space, few other models are more weighty, including the Kingwell Melodia and Apple AirPods Pro 3. The units come with four sets of ear tips in different sizes; the default mediums worked well for me.

The bigger issue isn’t how the tip of the device fits into your ear, though; it’s how the rest of the unit does. Lizn Hearpieces need to be delicately twisted into the ear canal so that one edge of the unit fits snugly behind the tragus, filling the concha. My ears may be tighter than others, but I found this no easy feat, as the device is so large that I really had to work at it to wedge it into place. As you might have guessed, over time, this became rather painful, especially because the unit has no hardware controls. All functions are performed by various combinations of taps on the outside of either of the Hearpieces, and the more I smacked the side of my head, the more uncomfortable things got.

Tech

Two Thinking Machines Lab Cofounders Are Leaving to Rejoin OpenAI

Thinking Machines cofounders Barret Zoph and Luke Metz are leaving the fledgling AI lab and rejoining OpenAI, the ChatGPT-maker announced on Thursday. OpenAI’s CEO of applications, Fidji Simo, shared the news in a memo to staff Thursday afternoon.

The news was first reported on X by technology reporter Kylie Robison, who wrote that Zoph was fired for “unethical conduct.”

A source close to Thinking Machines said that Zoph had shared confidential company information with competitors. WIRED was unable to verify this information with Zoph, who did not immediately respond to WIRED’s request for comment.

Zoph told Thinking Machines CEO Mira Murati on Monday he was considering leaving, then was fired today, according to the memo from Simo. She goes on to write that OpenAI doesn’t share the same concerns about Zoph as Murati.

The personnel shake-up is a major win for OpenAI, which recently lost its VP of research, Jerry Tworek.

Another Thinking Machines Lab staffer, Sam Schoenholz, is also rejoining OpenAI, the source said.

Zoph and Metz left OpenAI in late 2024 to start Thinking Machines with Murati, who had been the ChatGPT-maker’s chief technology officer.

This is a developing story. Please check back for updates.

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoUK says provided assistance in US-led tanker seizure

-

Entertainment1 week ago

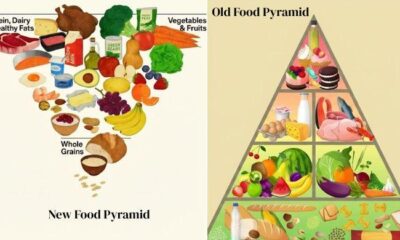

Entertainment1 week agoDoes new US food pyramid put too much steak on your plate?

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoWhy did Nick Reiner’s lawyer Alan Jackson withdraw from case?

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoTrump moves to ban home purchases by institutional investors

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoPGA of America CEO steps down after one year to take care of mother and mother-in-law

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoClock is ticking for Frank at Spurs, with dwindling evidence he deserves extra time

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoBulls dominate as KSE-100 breaks past 186,000 mark – SUCH TV

-

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoGold prices declined in the local market – SUCH TV

-Reviewer-Photo-SOURCE-Louryn-Strampe%25201.png)

-Reviewer-Photo-SOURCE-Louryn-Strampe%25202.png)