Business

Kohl’s names Michael Bender as permanent CEO after a turbulent year and sales declines

Kohl’s said Monday that Michael Bender, who has served as its interim CEO, will become its permanent chief executive as the department store tries to get back to sales growth.

He becomes the third CEO for the department store in about three years. The move is effective as of Sunday.

Bender, who has been director of Kohl’s board since July 2019, became the company’s interim CEO in May. The retailer appointed Bender to the position after firing CEO Ashley Buchanan after just a few months into his tenure.

Kohl’s fired Buchanan after it said a company investigation found that he had pushed for deals with a vendor with whom he had a personal relationship. That person was Chandra Holt, a former retail executive who had a romantic relationship with Buchanan.

Kohl’s leadership announcement comes a day before the retailer reports fiscal third-quarter earnings. Along with leadership turmoil, Kohl’s has struggled with declining sales. The company said in August that it expects net sales to drop by 5% to 6% for the fiscal year.

Kohl’s has had many changes at the top since former CEO Michelle Gass left the company in 2022 to join Levi Strauss & Co., where she later succeeded then-CEO Chip Bergh. She was followed at Kohl’s by Tom Kingsbury, a then-board member of the company, who became interim and then permanent CEO.

Michael Bender named Kohl’s Interim CEO.

Courtesy: Kohl’s

Bender, 64, previously held leadership and management roles at retailers including Victoria’s Secret, Walmart and Eyemart Express. Along with his role as CEO, Bender will continue to serve on the company’s board.

In a news release, board chair John Schlifske said Kohl’s hired an external firm and “conducted a comprehensive search” for the retailer’s new leader. He said Bender is the right person for the job because of his “three decades of leadership experience across retail and consumer goods companies and a deep commitment to the Kohl’s brand.”

“Over the past several months as interim CEO, Michael has proven to be an exceptional leader for Kohl’s – progressively improving results, driving short and long-term strategy, and positively impacting cultural change,” he said.

In a CNBC interview, Bender described Kohl’s turnaround as “heading toward close to the middle innings.”

“For me, that’s a good thing, because it means there’s still good work to be done, and ideas and challenges to bring forward to solve,” he said.

At Kohl’s, he said customers have “a lot of excitement,” but also “a more discerning, choiceful attitude about the dollars they spend.”

“What they’re looking for from retailers is curating assortment for me of quality products at a value that compels me to either get off the couch, or if I want to stay on the couch, to get on my phone and and order from you because they signify value for me,” he said.

Over the past five years, Kohl’s shares have fallen by about 53%. So far this year, its stock is up nearly 12%.

— CNBC’s Courtney Reagan contributed to this report

Business

West Asia conflict: Govt may ask companies to cut exports, increase auto fuel, LPG supplies – The Times of India

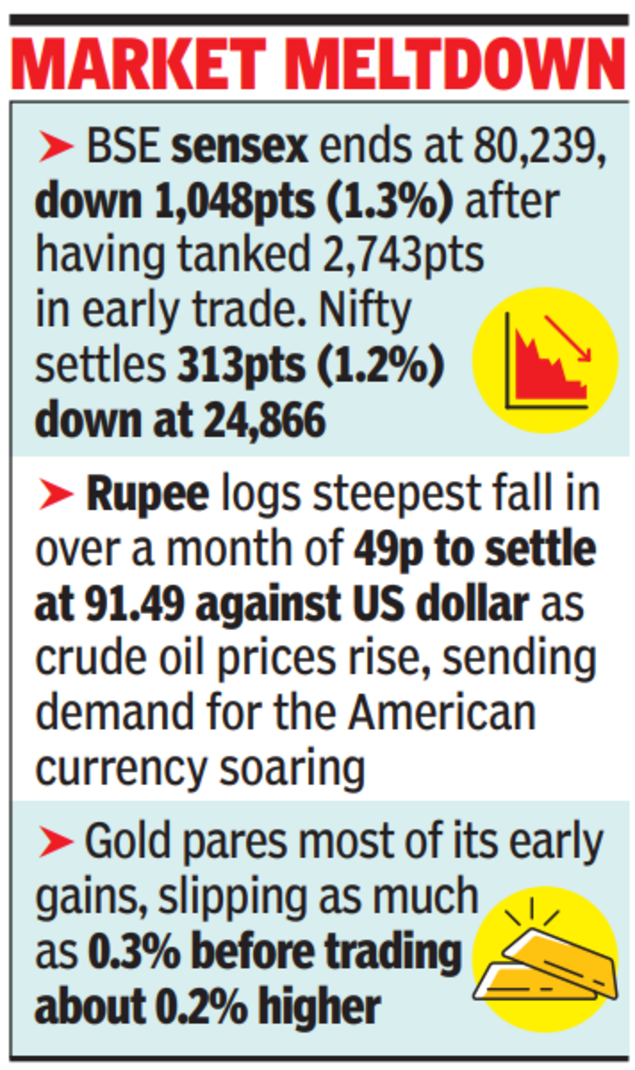

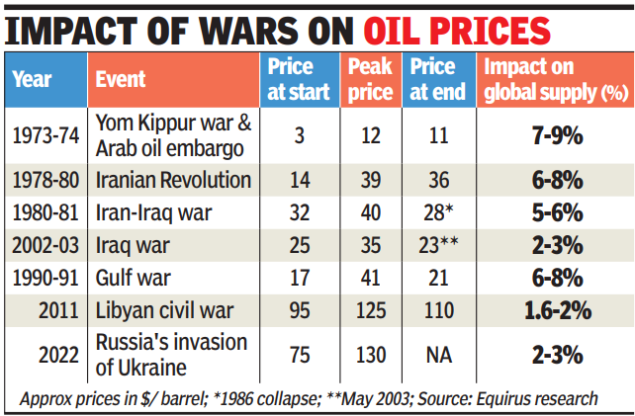

NEW DELHI: Amid fears of a shortage in crude supplies, govt is looking to nudge refiners to divert more auto fuel and LPG to the domestic market by cutting on exports and also increase cooking gas production so that there is no disruption in local supplies.While govt and oil companies insisted there’s no shortage, refiners are looking at alternate sources to partly compensate for crude coming from war-hit West Asia.

The tension has led to a spike in oil and gas prices, and given India’s dependence on imports, inflating the import bill and stoking inflationary pressures. Officials, however, said retail fuel prices may not rise immediately, as oil marketing companies follow a calibrated approach — absorbing losses when global prices are high and recouping them when prices soften. Retail petrol and diesel prices have remained unchanged since April 2022.Mantri meets oil cos to assess availability of crude and gasOn a day when Iranian drones damaged part of Saudi Aramco refinery and Qatar Energy’s facilities, the world’s largest LNG producer, announced an export pause, petroleum minister Hardeep Singh Puri and his team of officials met oil companies on Monday to assess the availability of crude and gas. “We are continuously monitoring the evolving situation, and all steps will be taken to ensure availability and affordability of major petroleum products in the country,” the oil ministry said in a post on X.India imports nearly 90% of its crude requirement. It also meets 60-65% of its LPG demand and about 60% of its LNG needs through imports, largely from West Asia, with shipments routed via Strait of Hormuz, which risks being choked due to the war.

According to the International Energy Agency, in 2023, 5.9% of the country’s production was being exported. Between April and Dec 2025, India exported petroleum products worth nearly $330 billion, with the Netherlands, UAE, the US, Singapore, Australia and China being the main destinations. In 2024, it also exported petroleum gas worth $454 million, mostly to Nepal, China, and Myanmar. The Reliance refinery in Jamnagar is the largest exporter in the country.An oil company executive said refiners are already in contact with traders to tie up capacities amid fears of the blockade of Strait of Hormuz. By Monday, the global market had caught the jitters from Qatar’s decision to suspend gas shipments.An oil executive said while disruption could cause difficulties in the immediate term, Indian players had a wide portfolio that they can tap for LNG, including the US, with vessels being routed through the Suez Canal.“Even if there is a force majeure, we have other sources of supply, which we can tap. Besides, no one is going to stop supplies indefinitely,” the executive said. While oil and gas prices rose Monday, the focus is on ensuring that supply lines remain open.

Business

Travel stocks fall after thousands of flights grounded following Iran strikes

A display board shows canceled flights to Dubai and Doha amid regional airspace closures at Noi Bai International Airport, amid the U.S.-Israel conflict with Iran, in Hanoi, Vietnam, March 2, 2026. Picture taken with a mobile phone.

Thinh Nguyen | Reuters

Airline and travel stocks slipped Monday after airspace closures throughout the Middle East forced carriers to cancel thousands of flights, disrupting trips as far as Brazil and the Philippines.

Cruise lines stocks also fell sharply, with Royal Caribbean Cruises dropping 3% and Carnival Corp. losing more than 7%.

Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings‘ stock fell 10% after its earnings call disappointed investors. Elliott Investment Management said last month that it had built a more than 10% stake in the company and that it’s seeking changes. New CEO John Chidsey told analysts that “our strategy is sound, our execution and coordination have not been, and a culture of accountability is essential and necessary going forward.”

Oil prices also rose, potentially driving up airlines’ biggest cost after labor. Flights through the Middle East were grounded, including to destinations like Tel Aviv and Dubai.

United Airlines, which has the most international exposure of the U.S. carriers, fell nearly 3%. Service to Tel Aviv, Israel, one of the airline’s most profitable routes, was halted, but airlines were also was forced to pause flights to Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, one of the busiest airport hubs in the world. Dubai is also a home base for the airline Emirates.

Shares of American Airlines lost 4% while Delta Air Lines fell 2%.

More than 11,000 Middle East flights have been canceled since the U.S.-Israeli strikes this weekend, according to aviation-data firm Cirium.

International travel has been a bright spot in the travel sector. In January, international air travel demand jumped 5.9% from a year ago while domestic flight demand was nearly flat, the International Air Transport Association, an airline industry group, said in a report Monday.

— CNBC’s Contessa Brewer contributed to this report.

Business

Brewdog: Bars close and hundreds lose jobs as beer firm sold in £33m deal

Beverage and cannabis company Tilray acquires the brewery, the brand and 11 bars after Brewdog went into administration.

Source link

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoHouseholds set for lower energy bills amid price cap shake-up

-

Entertainment1 week ago

Entertainment1 week agoTalking minerals and megawatts

-

Sports1 week ago

Sports1 week agoEileen Gu comments on Alysa Liu’s historic gold medal

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoLucid widely misses earnings expectations, forecasts continued EV growth in 2026

-

Politics5 days ago

Politics5 days agoWhat are Iran’s ballistic missile capabilities?

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoSri Lanka’s Shanaka says constant criticism has affected players’ mental health

-

Tech6 days ago

Tech6 days agoHere’s What a Google Subpoena Response Looks Like, Courtesy of the Epstein Files

-

Politics1 week ago

Politics1 week agoSupreme Court ruling angers Trump: Global tariffs to rise from 10% to 15%